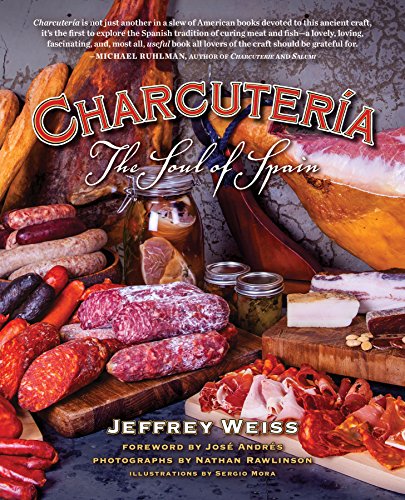

Charcutería: The Soul of Spain - Hardcover

2015 Gourmand World Cookbook Award nominee

Charcutería: The Soul of Spain is the first book to introduce authentic Spanish butchering and meat-curing techniques to America. Included are more than 100 traditional Spanish recipes, straightforward illustrations providing easy-to-follow steps for amateur and professional butchers, and gorgeous full-color photography of savory dishes, Iberian countrysides, and centuries-old Spanish cityscapes.

Jeffrey Weiss has written an entertaining, extravagantly detailed guide on Spanish charcuterie, which is deservedly becoming more celebrated on the global stage. While Spain stands cheek-to-jowl with other great cured-meat-producing nations like Italy and France, the unique charcuterie traditions of Spain are perhaps the least understood of this trifecta. Americans have most likely never tasted the sheer eye-rolling deliciousness that is cured Spanish meats: chorizo, the garlic-and-pimentón-spiked ambassador of Spanish cuisine; morcilla, the family of blood sausages flavoring regional cuisine from Barcelona to Badajoz; and jamón, the acorn-scented, modern-day crown jewel of Spain's charcutería legacy.

Charcutería is a collection of delicious recipes, uproarious anecdotes, and time-honored Spanish cuisine and culinary traditions. The author has amassed years of experience working with the cured meat traditions of Spain, and this book will surely become a standard guide for both professional and home cooks.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

José Andrés was named Outstanding Chef” by the James Beard Foundation in 2011. He is an internationally recognized culinary innovator, cookbook author, television personality, hunger issues advocate, and the chef/owner of ThinkFoodGroup. He lives in Bethesda, MD.

Nathan Rawlinson is a James Beard-nominated photographer based in New York City. He graduated from the Culinary Institute of America and worked at Eleven Madison Park as a manager and sommelier for four years before starting his photography business. His work has been featured in The New York Times, Time.com, and GrubStreet.com.

Sergio Mora is an illustrator based in Barcelona.

Understanding the Spanish gastronomy of today and how it continues to influence

the American gastronomy of tomorrow

Madrid

Manolo our faithful friend and barkeep at this dive-bar for cooks speaks in his cigarette smoke-laden Spanish baritone and fixes me with a glare that dares me to disagree:

Nunca has probado una morcilla como esta, Americano.”

Sadly, I realize he’s right which is really all he wanted to hear anyways.

You have never tasted a morcilla like this one, American.”

These are some fiercely partisan culinary fightin’ words the type spoken in bars all around Madrid over cañas of beer and, in this instance, a ración of cured blood sausage from Jaén called morcilla achorizada. This morcilla, unlike other blood sausages from around the world, is a mixture of chorizo masa mixed with pig’s blood, cooked potato, rice, onions, and spices. The stuffed morcilla is then smoked and dry cured.

And it is utterly delicious; sabroso in a way that makes me angry you can’t find anything like this where I live because it’s almost impossible to find this morcilla achorizada outside of Spain and definitely not in the United States.

Thanks for rubbing it in, cabrón” I manage with a sarcastic smile while stabbing the last slice with a toothpick. The truth is that this is easily one of the best embutidos I have ever tried and it makes me consider with the manic obsession of a heroin junkie getting helter-skelter for another hit how I could possibly bring some of these wrinkled, black delights back home to California without causing an international incident at the US customs checkpoint.

Andalucía

In Granada is a small, inconspicuous alleyway that houses one of the best flamenco clubs in Spain. You would never know it the only advertisement is a dimly-lit, sun-washed wall with black lettering and a scraggly, hastily-painted arrow pointing you deeper into the abyss. To make matters worse, this club is only open at night which was when I found myself late one summer evening staring into this great unknown:

It says: Eshavira Club.”

Standing there in the moonlight confronted by the deafening stillness of this portal leading to God-knows-where I realized that at times like these there are two types of people in the world:

There are those who look down that alley and, acknowledging their lack of the requisite testicular fortitude, quickly sprint away with their tail between their legs; and then there those spurned on by a chemical courage borne of the local inebriant of choice who follow that arrow onwards to their destiny.

With a few hesitant steps made easier by said inebriant, I joined the latter group.

Much, much later minutes or hours or days had passed I emerged from that passage to a bright new day in southern Spain. I was generally unscathed as I stumbled into the light be-speckled in crooked sunglasses, but something was different about this world around me; this Andalusian culture with its veneer of Moorish influence everywhere you look finally made so much beautiful sense.

What did I find in the depths of that alley, you ask?

I found a confluence of cultures a place lost in time yet wholly comfortable in the present; a consortium for flamenco and the people who cling to the practice of an ever-evolving art; a place where old and older is not afraid to mingle with the new, the modern, and even the tragically hip.

I found an ancient wooden door; a bouncer with a one-word name; a bar that serves beer or sangria y nada mas; and a universe centered upon a dusty, worn stage manned by men and women who stomp, clap, and sing the spirit of Gitano pain and pride.

I found a small piece of the Andalusian soul.

Extremadura

It’s a good day to die, little piggies.

Here, 45 minutes away from the nearest city, herds of Ibérico pigs roam tree-to-tree searching for acorns to eat. They do their best to avoid the butchers in blue coveralls knives in hand stalking the herd to cull three members for our matanza, the wintertime ritual pig slaughter/alcohol-and-pork-fueled party with deep roots in Spanish antiquity.

The Ibérico pigs are anything but pretty they are closely related to wild boars but they possess a unique manner in which they store large quantities of their fat intramuscularly. It is this characteristic, plus the resulting flavor of that fat from the acorns my delicious little friends gorge themselves on during the montanera the acorn-feeding months prior to slaughter that makes their meat so coveted and expensive.

At The Rocamador, a gorgeous converted monastery and four-star-hotel situated in the countryside of rugged Extremadura, the Tristancho family has been conducting matanzas for their guests often comprised of chefs and the social elite of Madrid for years. These guests are taken out to the farm, participate in a slaughtering ritual dating back to the earliest Iberian settlers, and then reap the rewards of their labor through porcine-and-alcohol-laden payment.

So it is here that I found myself with the opportunity any line cook would dream of; learning about Spanish pork butchery and charcuterie in the heart of Ibérico country; and mixing a local specialty sausage with a gaggle of Extremeñan mothers and grandmothers when my education and hazing concurrently began:

Jeffrey” (pronounced Yeh-free” here in the heart of Extremadura), ¿Como está tu chorizo?”

Translated: Jeffrey, how is your sausage?” (Chorizo was the type of sausage that I was stuffing into a casing using hand-motions you could only describe as masturbatory so, yes, the double entendre was very much intentional)

(Laughter)

Jeeeeefrey, ¿Qué chiquito es, no?

Translated: It’s a little small, right?”

(More double entendre, more laughter)

Jeeeeeeeeeeeeeefrey, y es blando también. ¿Le quieres dar un masaje?

Translated: And it’s limp too. Do you want me to give it a massage?”

(Now they are ROFL-ing.)

Apparently, this too was a tradition: the gentle teasing of any extranjero in the group’s midst (the FNG or Fucking New Guy, as someone like Anthony Bourdain would have appropriately described me in that moment). All the better that I was an American cook a gringo, a guiri, a white-boy initiated just enough in the language of the kitchen to understand what I was being asked to do and that I was definitely the butt of an inside joke.

Jeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeefrey: Ahora tu chorizo es perfecto.”

Es muy grande ¿eres el orgullo de tu madre, no?”

Translated: Your chorizo is perfect; it is very big. You must be your mother’s pride, no?”

A Spanish version of a Yo Momma” joke? I laughed too who wouldn’t? But retaliation was in order in the name of pride and my Momma:

Cuidado con este chorizo extranjero, Señora. ¿Creo que es demasiado grande para ti, no?

Translated: Be careful with this foreigner’s chorizo, ma’am. I think it’s a little big for you to handle, right?”

Score one for the extranjero.

So it was for weeks with mi familia Extremeña we ate, we drank, we took the lives of Ibérico pigs in the name of deliciousness and necessity, we connected with an age-old tradition of making charcutería just like these mothers and grandmothers did with their mothers and grandmothers, and they gave their hijo extranjero their foreign son a load of crap and an education in comida casera for which I am eternally grateful.

And all was right and delicious in the heart of Extremadura.

The Spain that I know

This is my Spain a Spain of transcendent memories centered on the food and culture of a people I have come to adopt as my own.

These memories are the staccato sounds of the flamenco bailaora’s footfalls, the multi-colored sights of pintxo platters laid out on bars in San Sebastian, and the unmistakable smells of charcutería that smoky aroma of cured pork mixed with pimentón that permeates much of Spanish cuisine, culture, history, and a national obsession and regional pride for various shapes, sizes, and flavors.

But while Spain stands porky cheek-to-jowl with other great cured meat-producing nations like Italy and France, the charcuterie traditions of Spain are perhaps the least-understood of this trifecta due to an almost infinite degree of regional variances and a miniscule degree of exportation, least of all to the United States. For example, importation of Spanish charcutería into the United States is limited to the handful of producers that can pass strenuous regulations set forth by the US Department of Agriculture and even then only a fraction of the products available in the Spanish market actually trickle through to American shores.

These restrictions coupled with a general misunderstanding of Spanish gastronomy that lumped it under the general heading of Hispanic cooking” in the 70s and 80s alongside the cuisines of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and much of Central and South America mean that a niche product such as traditional charcutería is just now coming into popularity.

This also means that you likely have never tasted the sheer eye-rolling deliciousness that is morcilla achorizada, fuet, or sobrassada a birthright for any Spaniard but something that, for extranjeros like you or me, is something we just have to place at the top of our bucket list.

Fortunately for us, however, Spanish cuisine is thriving. And that popularity comes thanks to a number of events over the past few decades: the globalization of world cuisines that finally includes classic Spanish culinary traditions (thanks in large part to people like Penelope Casas and Chef José Andrés who introduced Americans to much of traditional Spanish gastronomy); the foodie culture that permeates our collective consciousness via the internet, food shows, blogs, and other mediums; and the resurgence of artisan foods like charcuterie into the American culinary lexicon that has only recently hit its stride in the past several years.

What was old is new again

That last piece of the puzzle our return to artisan cuisine (meaning food that is hand-crafted, small-scale, made with an eye to quality and detail, and definitely not anything resembling a Domino’s pizza) has really been the catalyst for the rebirth of charcuterie traditions that are now so popular in restaurants and other operations across The United States.

As Chef Thomas Keller perfectly discusses in the foreword of Michael Ruhlman and Brian Polcyn’s book Charcuterie, these products have been all around us in decades-past, but mainly in the form of commercially-manufactured goods such as supermarket bolognas, hot dogs, and other meats of dubious origin. Today’s chef and butcher- driven charcuterie programs by contrast are sourcing specific animals from specific farms, often breaking down the animals in-house, and seeking to vertically-integrate the process from farm to table” in the name of producing the highest-quality product possible as opposed to cutting corners in search of the profit-making potential that the charcuterie-in-question has to offer.

Producers like Armandino Batali, Alan Benton, and Paul Bertoli; chefs like April Bloomfield, Jamie Bissonette, Chris Cosentino, and Brian Polcyn; and a multitude of others throughout the supply chain of farmer to consumer have pushed American gastronomy forward by helping us find our way back to the butchery and charcuterie traditions of our forefathers; traditions that were misplaced during the fast-paced, commercially-driven food culture of the past decades.

Which brings us to why I wrote this book.

My journey of a thousand meat-curing miles began with a single obsession that we, in the American public, have yet to fully be exposed to: the wide array of cured meats available in Spain.

Sure, our collective charcuterie IQ has increased over the past ten or so years:

We are generally acquainted with popular cured meats like mortadella and pepperoni. Hell, we even know various forms of prosciutto, kielbasa, and saucisson. But chorizos? Morcillas? Butifarras? No tenemos ni puta idea, amigos.

Spanish-style charcuterie is tremendously underrepresented, misunderstood, or largely unheard of in our country¬ as any ex-pat Spaniard who has futilely searched the United States for a taste of home knows. Due in large part to stifling restrictions on the importation of cured meats and a mostly-American misunderstanding of Spanish cuisine over the last few decades (case in point: no self-respecting Spanish abuela I know makes chicken with green olives,” even though many American cookbooks call this dish Spanish Chicken”), charcutería is simply is not represented in the global melting pot that American gastronomy has become.

That is why I embarked on a culinary odyssey that has spanned a decade: To introduce regional and national charcutería specialties that permeate the hearts and souls of the Spanish people and to provide a roadmap for producing and utilizing these recipes in case you don’t feel like braving a trans-Atlantic flight or US smuggling ordinances for your own slice of Extremadura, País Vasco, or Castilla-La Mancha.

That journey eventually brought me to the opportunity of a lifetime when I was accepted as 1of only 2 American cooks in the world selected for the ICEX scholarship a culinary scholarship sponsored by the Spanish government that allowed me to cook in the kitchens and countryside of Spain and allowed me the chance to make charcutería elbow-to-elbow with the maestros (or, more often than not, the maestras) of this craft.

Throughout this book, I will share parts of that journey in learning and practicing the art of charcutería and la cocina Española including introducing the cast of characters that have helped me on my way to understanding why the cuisine and culture of Spain is so unique and deserving of being celebrated on the world stage.

To begin, we will discuss the history of chorizos, jamones, and other forms of charcutería as they evolved through the ritual pig slaughters known as matanzas, finishing up with the modern age of industrialized charcuterie and the restrictions we face here in the United States.

From there, I will introduce you to something you have likely never seen before: Spanish pork butchery, which differs significantly from the methods utilized here in the United States. Specifically, we will look at the cerdo Ibérico the famously black Ibérico pigs making our way through the matanza ritual and Spanish-specific butchery cuts for a pig including cuts like the secreto, pluma, presa, aguja, and others. While I hope that you have the opportunity to seek out these cuts on your own, this information will also serve our purposes later on as we discuss the different parts required for different types of charcutería.

Next, we continue with the basics of charcutería, including the various steps for making fresh, semi-cured, dry-cured, and whole muscle charcuterie. We will also cover equipment and ingredient options that will help you get the job done, as well as the best ways for weighing, measuring, buying and practicing as you start curing your own meat.

Then we will get to el alma of the book the recipes and techniques that I learned from my time cooking, traveling, and learning with the chefs, sabias, and matanceros of Spain.

The recipes are broken up according to the major technique that you will learn and incorporate in each chapter. For many of these preparations, I will also include some favorite ways to utilize the charcutería of that chapter for making delicious and traditional dishes many of these recipes come straight from...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherAgate Surrey

- Publication date2014

- ISBN 10 1572841524

- ISBN 13 9781572841529

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages464

- IllustratorMora Sergio

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 3.25

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

CharcuterÃa: The Soul of Spain

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Mora, Sergio (illustrator). Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon1572841524

CharcuterÃa: The Soul of Spain

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Mora, Sergio (illustrator). New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think1572841524

Charcuter?a: The Soul of Spain

Book Description Condition: new. Mora, Sergio (illustrator). Seller Inventory # FrontCover1572841524

Charcuter?a: The Soul of Spain

Book Description Condition: new. Mora, Sergio (illustrator). Seller Inventory # newMercantile_1572841524

CharcuterÃa: The Soul of Spain

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Mora, Sergio (illustrator). New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_1572841524

CharcuterÃa: The Soul of Spain

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Mora, Sergio (illustrator). New. Seller Inventory # Wizard1572841524

Charcutería: The Soul of Spain

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Mora, Sergio (illustrator). Brand New!. Seller Inventory # VIB1572841524