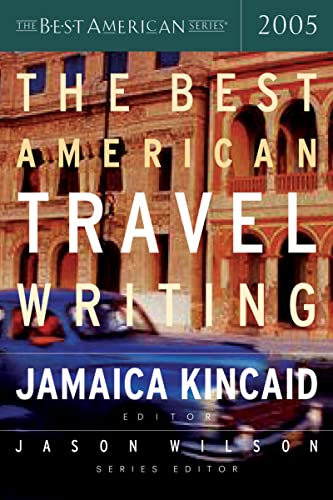

The Best American Travel Writing 2005 (The Best American Series) - Softcover

The Best American Travel Writing 2005 includes

William Least-Heat Moon · Ian Frazier · John McPhee · William T. Vollmann · Simon Winchester · Tom Bissell · Madison Smartt Bell · Timothy Bascom · Pam Houston · and others

Jamaica Kincaid, guest editor, is the author of numerous award-winning works, including the memoirs My Brother and The Autobiography of My Mother and the novel Annie John. Her travelogue Among Flowers: A Walk in the Himalayas appeared in 2005. She lives in Vermont with her two children and a garden, in which she travels a great deal.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

JASON WILSON is the author of Godforsaken Grapes: A Slightly Tipsy Journey through the World of Strange, Obscure, and Underappreciated Wine and Boozehound: On the Trail of the Rare, the Obscure, and the Overrated in Spirits. He writes regularly for the Washington Post and the New York Times. Wilson has been the series editor of The Best American Travel Writing since its inception in 2000. His work can be found at jasonwilson.com.

JAMAICA KINCAID is the author of numerous award-winning works, including the memoirs My Brother and The Autobiography of My Mother, the travelogue Among Flowers: A Walk in the Himalaya and the novels Annie John and My Favorite Tool. She is a contributor to The New Yorker and has also appeared in “The Sophisticated Traveler” in the New York Times.

The travel writer: She is not a refugee. Refugees don’t do that, write travel narratives. No, they don’t. It is the Travel Writer who does that. The Travel Writer is a dignified refugee, but a dignified refugee is no refugee at all. A refugee is usually fleeing the place where the Travel Writer is going to enjoy herself but later, for the Travel Writer tends to enjoy traveling most when not doing so at all, when sitting at home comfortably and reflecting on the journey that has been taken.

The Travel Writer doesn’t get up one morning and throw a dart at a map of the world, a map that is just lying on the floor at her feet, and decide to journey to the place exactly where the dart lands. Not so at all. These journeys that the Travel Writer makes begin with a broken heart sometimes, a tender heart fractured, its sweet matter bejeweled with the sharp slivers of a special pain. Or these journeys that the Travel Writer makes begin in curiosity but not of the Joseph Dalton Hooker kind (Imperial Acts of Conquests) or of the Lewis and Clark kind (Imperial Acts of Conquests) or of the William Wells Brown kind (an African American slave who freed himself and then traveled in Europe and wrote about it). No, not that kind of curiosity but another kind, a curiosity that comes from a supreme contentment, comfort, and satisfaction with your place in the world and this benevolent situation, so perfect and so just, it should be universally distributed, it should be endemic to individual human existence, and would lead an unexpected anyone to go somewhere and write about it. In this case, everyone who goes anywhere and notices her surroundings and finds them of interest will be a Travel Writer.

* This person I have been describing, the Travel Writer, almost certainly is myself. And also this person I have been describing reflects the writers of these essays in this anthology. Especially because I have selected these essays, I see the writers and their motives in much the same way I see my own. I will not be disturbed when they object. I will only continue to see them in this way.

At the beginning of the travel narrative is much confusion, for even though when sitting down to write, to give an account of what has recently transpired, the outcome is known, has been a success; the Travel Writer must begin at the beginning. The beginning is a cauldron of anxiety (the passport is lost, the visa might be denied, the funds to finance the journey are late in coming, a child comes down with a childhood disease). Things all work out, she is on the boat or the airplane or the train. Or he is in the restaurant, eating something that is delicious (that would be William Least Heat- Moon?), but even so there is no respite. For the traveler (who will eventually become the Travel Writer) is in a state of displacement, not in the here of the familiar (home), not in the there of destination (a place that has been made familiar by imagining being in it in the first place). That time between the here that is truly familiar and the here that has come through imagining, and therefore forcibly made familiar, is dangerous, for the possibility of loss of every kind is so real. Yet the Travel Writer, travel narrator, will persist. Nothing can stop her, only death, the unexpected failure of the human body, the airplane falls out of the sky, the ship sinks, the train bolts from its rails and falls headlong into the deepest part of the river. She eventually arrives at her destination; she begins to collect the experience that will constitute the work of the Travel Writer. She gathers herself up, a vulnerable bundle of a human being, a mass of nerves, and she begins.

The first time I traveled anywhere, I was not yet a writer, but I can now see that I must have been in the process of becoming one. I was nine years old and had been the only child in my family until then, when, suddenly it seemed to me, my first brother was born. My mother no longer paid any attention to me; she seemed to care only about my new brother. One day, I was asked to hold him and he fell out of my arms. My mother said that I had dropped him, and as a punishment, she sent me off to live with her sister and her parents, all of whom she hated. They lived in Dominica, an island, one night’s distance by steamer boat away. The boat I sailed on was called M. V. Rippon, and it traveled up and down the British Caribbean with a cargo of people, goods, and letters. No one I knew personally had ever sailed on it, but it often brought to our home angry exchanges of letters from my mother’s family. And sometimes it also brought to us packages of cocoa, cured coffee beans, castor oil, unusually large grapefruits, almoonds, and dasheen, all of these things my mother’s family grew on their plantation. The angry letters and the produce came from the sssssame place and from the same people.

It was to this place and these people that my mother sent me as a punishment for dropping my new and first brother on his head. The M. V. Rippon, which had until then been so mysterious, a great big, black hulk, with a band of deep red running all around its upper part, appearing every two weeks, resting in a deep part offshore from Rat Island for a day or two and then disappearing for another two weeks, soon became so well known to me that I have never forgotten it. My mother took me on board, abandoned me in a cabin that I was to share with another passenger, a woman she and I did not know, and then left. Even before the Rippon set sail my stomach began to heave. It never stopped; my stomach heaved all night. My nine-year-old self thought I would die, of course, but I didn’t. After eternity (and I did not experience this as an eternity; I experienced it as the thing itself, Eternity), it was morning and I looked out through a porthole and saw a massive green height in front of me. It was Dominica. Slowly the Rippon pulled into port. It was raining, and it was raining as if it had been doing so for a long time and planned to continue doing so for even longer than that. All the passengers got off the boat. I could not. There was no one to greet me. In my nine years I had never known this feeling, a feeling with which I am now, at fifty-six, quite familiar: displacement, the feeling that I had lost my memory because what I could remember had no meaning right then; I could not apply it to anything in front of me; I did not know who I was. I remembered that I was my mother’s daughter, but between that and the place I was then, the jetty in Roseau, Dominica, that person had been lost or modified or transformed, and there was nothing and no one on the jetty in Roseau, Dominica, to help me be myself again, the daughter of my mother.

I believe it was the captain of the Rippon, or someone like that, someone in charge of things, who got a car with a driver to take me to the village of Mahaut, which was where my mother grew up and where her family still lived. But the voyage from the jetty in Roseau to the village of Mahaut was as difficult a journey in its way as had been the voyage from Antigua to Dominica. This new landscape of an everlasting green, broken up into lighter green and darker green, was not even in my imagination. I had never read a description of it. Perhaps I had read about it and thought it not believable.

Perhaps my mother had told me about it, for she told me so many things about her childhood and this place in which she grew up, but such a detail as this, the way the land lay, the look of things, did not make an impression, not a lasting, memorable one. In any case, I had thought that mountains were something in my geography book, not something in real life. I had thought that constant rainfall was something in a chapter of unusual natural occurrences, not something everyday.My mother did not tell me that in her growing up, it rained nine months of the entire year. It explained much about her, but I could not have put it into words then; I didn’t know her really then. And then the roads were winding but in a dangerous way. They wound around the sides of the mountain, sharply. On one side of the road was the side of the mountain, which went up to a height that I did not know existed, for Antigua is a flat island with some hills here and there; on the other side of the road was always a precipice, a sharp deep drop to the bottom. My aunt, my mother’s sister, was made lame while riding a bicycle on one of these roads, and she went around a sharp turn incorrectly and fell into one of these precipices on the road between Roseau and Mahaut when she was young. I arrived at the house, the home wheremy mother grew up. Her sister had not been opening her letters for a while now (this is a tradition that I have kept up, not opening letters from people with whom I amhaving a quarrel) and so had no idea that my mother had decided to send me to live with her family. She seemed glad to see me. She had never seen me in real life; she only knew of me through my mother’s letters. I almost attended her wedding, but then my family couldn’t afford to send me to it. She seemed glad to see me. But I didn’t like her, my aunt, for she didn’t like my mother. I immediately began to plan to leave. My stay with them, my mother’s family, was openended. I think it was meant to last until I grew up, and no longer wanted to see my little brother dead. By the time I got to Mahaut, I had forgotten that I wanted him dead. I only wanted to go home to my mother.

I went to school in Mahaut. I learned how to walk in the rain. In Antigua, it rained so infrequently that when such a thing did happen, rain, the streets became empty of people. It was as if we didn’t know how to exist normally with such a thing as rain. People would say, I wanted to do such and such a thing, but I couldn’t because it was raining, and such a statement was always met with incredible sympathy and understanding. We did nothing, when it was raining, in Antigua. In Dominica, the rain falling was the same as the sun shining; it was all met with indifference. I learned how to use a cutlass. I learned the meaning of the word homesickness. At the end of each day, when the sun was about to drop suddenly into the depths beneath the horizon and the onset of the blackest of nights would dramatically come on, I did not think I would lose my mind; I did not think I would die. I thought I would live in this way, in this blackness, this place where in the dark everything lost its shape even when you touched it and could run your hands over its contours, forever, that night would never end.

From the beginning, I began to think of ways to get out of this place. But I could not find a solution. There was nothing wrong. My mother’s father was of no interest to me, but my mother’s mother was very special. She quarreled with the rest of her family and so never had anything to do with them. She cooked her own food and ate it all by herself. After a while, I liked her so much that I was allowed to be with her all the time. I would squat with her over a fire as she roasted coffee beans and then ground them and then made us little cups of coffee that had a small mound of sugar at the bottom of the cup. I liked her green figs with flying fish cooked in coconut milk better than I liked my mother’s. She and I even slept in the same bed. That was the wonderful part. Still, I wanted to go home; I wanted to go back to my mother.

I wrote to my mother the usual sorts of letters: How are you? I am well. I miss you very much. But in my school notebook, the one that had a picture of the Queen of England and her husband on the cover, I wrote another kind of letter, and these had some very harsh and untrue things about my daily life as I lived it with my mother’s family. In that notebook, I wrote that my aunt hated me and often beat me harshly. I wrote that she sent me to bed without my dinner. I wrote that she did not allow me to bathe properly, leaving my private parts unclean and that my unwashed body smelled in a way that made my classmates avoid me. I wrote those things over and over again in that notebook, but after I wrote them down, I would tear out the page from the book, fold it up, and hide it in under a large stone outside near the hedge of periwinkle that grew in the garden. I did not mean for these letters to be found; I did not mean that anyone else should read them. All the same inevitably, no doubt my aunt found them and after she read them became ablaze with anger, and my mother and I became one to her, a despicable duo to be banished forever from her presence, and she placed me on the M. V. Rippon the next time it was due back in Dominica to make a voyage to Antigua.

No detail of my return to Antigua is clear to me now; I only wanted to arrive there. I did, of course, and found my mother even more lost to me than before. She had given birth to another son, my second brother, and she loved me even less, as she loved my brothers even more. It was at eleven years of age that I began to wish for the journey out that led to my life now. I did not know then that it would be possible; I most certainly did not know of the sharp turns and deep precipices that existed and continue to exist to this day.

And what of the essays here? Every one of them reminds me of two of the many sentiments attached to the travel narrative: curiosity and displacement. None of them are about a night’s stay in a nice hotel anywhere; none of them chronicle a day at a beach. They were not chosen to say something about the state of American travel writing; they were chosen because I simply liked them. And I chose these travel narratives: John McPhee’s Tight-Assed River,” Ian Frazier’s Route 3,” Jim Harrison’s A Really Big Lunch,” Thomas Keneally’s Romancing the Abyss,” Bucky McMahon’s Adrift,” Robert Young Pelton’s Into the Land of bin Laden,” Tom Ireland’s My Thai Girlfriends,” Peter Hessler’s Kindergarten,” Kira Salak’s The Vision Seekers,” Timothy Bascom’s A Vocabulary for my Senses,” Tom Bissell’s War Wounds,” Charles Martin Kearney’s Maps and Dreaming,” Seth Stevenson’s Trying Really Hard to Like India,” William E. Blundell’s My Florida,” and Pam Houston’s The Vertigo Girls Do the East Tonto Trail,” and the rest of the entire table of contents, for they all hold an idea that is so central to my own understanding of the world I have inherited. These essays stimulate my curiosity; they underline my sense of my displacement.

How I like that, the feeling of being out of place. And again, what of the essays here? Reading John McPhee’s Tight-Assed River” and Ian Frazier’s Route 3” again and again, for the pleasure of the writing itself, and this pleasure is a sort of journey too. For as I read these two essays, I kept saying to myself, how did he do that, in wonder at the beauty of the sentences. And then there is the deliciously funny Trying Really Hard to Like India” by Seth Stevenson and the truly hilarious The Vision Seekers” by Kira Salak. I will stop here.

But before I do, here is this: Not so long ago, I was in Nepal, walking about in the foothills around Makalu and Kanchenjunga, collecting seeds for my flower garden. The journey was full of the usual difficulties: avoiding being killed by Maoist guerillas, avoiding being killed by the constantly shifting landscape. I was not killed by anything, and I also collected the seeds of many different plant specimens. While there, I liked being in that place, and I liked what I was doing. I returned home and to this day, the memory of it pleases me.

Read these essays, close the book, sit back, and just wait, but you won’t have to wait for too long.

Jamaica Kincaid

Copyright © 2005 by Houghton Mifflin Company. Introduction copyright © 2005 by Jamaica Kincaid. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Company.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherHoughton Mifflin

- Publication date2005

- ISBN 10 061836952X

- ISBN 13 9780618369522

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages374

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Best American Travel Writing 2005 (The Best American Series)

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # ZBM.13U0V

The Best American Travel Writing 2005 (The Best American Series)

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. In shrink wrap. Seller Inventory # 90-15665

Best American Travel Writing 2005

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 3473903-n

The Best American Travel Writing 2005 (Paperback or Softback)

Book Description Paperback or Softback. Condition: New. The Best American Travel Writing 2005 0.99. Book. Seller Inventory # BBS-9780618369522

The Best American Travel Writing 2005 (The Best American Series)

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # ABLIING23Feb2416190080172

The Best American Travel Writing 2005 (The Best American Series) [Paperback ]

Book Description Soft Cover. Condition: new. This item is printed on demand. Seller Inventory # 9780618369522

The Best American Travel Writing 2005 (The Best American Series)

Book Description Condition: New. Buy with confidence! Book is in new, never-used condition. Seller Inventory # bk061836952Xxvz189zvxnew

The Best American Travel Writing 2005 (The Best American Series)

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Seller Inventory # 353-061836952X-new

The Best American Travel Writing 2005 (The Best American Series)

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # I-9780618369522

The Best American Travel Writing 2005 (The Best American Series)

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_061836952X