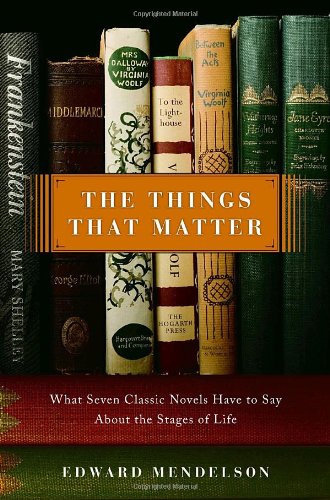

The Things That Matter: What Seven Classic Novels Have to Say About the Stages of Life - Hardcover

For Edward Mendelson—a professor of English and comparative literature at Columbia University—these classic novels tell life stories that are valuable to readers who are thinking about the course of their own lives. Looking beyond theories to the individual intentions of the authors and taking into consideration their lives and times, Mendelson examines the sometimes contradictory ways in which the novels portray such major passages of life as love, marriage, and parenthood. In Frankenstein’s story of a new life, we see a searing representation of emotional neglect. In Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre the transition from childhood to adulthood is portrayed in vastly different ways even though the sisters who wrote the books shared the same isolated life. In Mrs. Dalloway we see an ideal and almost impossible adult love. Mendelson leads us to a fresh and fascinating new understanding of each of the seven novels, reminding us—in the most captivating way—why they matter.

The Things That Matter is a book that will delight all passionate readers.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

birth: Frankenstein

Frankenstein is the story of childbirth as it would be if it had been invented by someone who wanted power more than love.

The book’s subtitle identifies Victor Frankenstein as “The Modern Prometheus.” The ancient Prometheus stole fire from the gods so that he could give human beings its warmth and comfort. The modern Prometheus steals from nature “the cause of generation and life”—the secret of biological reproduction by which a new life is brought into being—and uses that secret to create a new species. In human beings the power of “generation and life” works through the partly instinctual, partly voluntary union of a man and woman who have little control over the outcome, and who typically feel—as Victor remembers his parents feeling about him—a “deep consciousness of what they owed towards the being to which they had given life.” Victor, in contrast, feels no obligation to the being to which he has given life through “the horrors of my secret toil,” and he sustains himself through his gruesome, pleasureless work with the thought that his creature will owe him more gratitude than any human child ever owed to its father. Frankenstein performs the act of creation alone, by conscious choice rather than through instinct, so that he alone can have total control over its outcome.

Victor creates new life by applying an electric spark to a dead body, not by embracing a living one. In this act and in every other he rejects his own bodily life, the bodily lives of those who love him, and the whole realm of the flesh. While building his creature, he “tortured the living animal to animate the lifeless clay.” Later, while building a mate for the creature, Victor is so horrified by the prospect of their having children of their own that, “trembling with passion,” he “tore to pieces the thing on which I was engaged.” Victor thinks of his own impending marriage with “horror and dismay,” and some of his feelings are justified by his creature’s threat to be “with you on your wedding-night.” But the deeper cause of his dismay is something that the book never names explicitly, but which it insistently points to—Victor’s deep, unacknowledged horror of the human body and its relations with another human body. One effect of what he calls his “murderous machinations” is the murder of his own bride on their wedding night.

Choosing Beauty

The body is the part of yourself which is most obviously created and shaped by nature. No one can ever fully control its appetites, instincts, and desires, especially the impulses that erupt without warning at the end of childhood, when the body becomes sexually mature. Everyone wants to achieve at least some control over them, but Victor Frankenstein wants the total control over the flesh that he can attain by making a body to his own specification. His ambition is not merely to gain control over his own body—although he drives it to exhaustion and withholds satisfactions from it—but to conquer nature itself, to seize for his own use that mysterious instinctive power that gave his body life. “I pursued nature to her hiding-places,” he says of his researches, as if he were a hunter and nature his prey.

When a child is born, nature determines whether or not it will have physical beauty, but Victor chooses for himself the appearance that he gives his creature: “His limbs were in proportion, and I had selected his features as beautiful.” (The modern couple who advertises for a blond, blue-eyed egg donor is driven by a similar wish to control a new life.) He gives the creature the spark of life; he refuses it the warmth of his feelings. When Victor’s work is done and the creature opens its eyes, reaches out its hand, and tries to smile at its creator, Victor flees in dismay. Earlier, when the creature existed only as an inert, lifeless thing in his laboratory, Victor could enjoy fantasizing about the gratitude it would give him, but as soon as the object of his generosity takes on a life of its own, as soon as it breaks free of his fantasies about it, “the beauty of the dream vanished, and breathless horror and disgust filled my heart.” From this point onward, he thinks of his creature as “my enemy”—but the only thing it has done to deserve Victor’s horrified disgust is to reach out for his affection.

What the creature wants from his creator is “sympathies,” a word that recurs throughout Frankenstein. “Sympathy” was the word used in Mary Shelley’s time for all the feelings of mutual understanding and affection that join individuals to each other. Sympathies bring together friend and friend, parent and child, wife and husband. The creature demands that Victor build a mate “with whom I can live in the interchange of those sympathies necessary for my being,” and Victor later reflects that “one of the first results of those sympathies for which the daemon thirsted would be children.” The sympathies the creature wants from Victor are those of a parent for a child. Victor offers only hatred.

But Victor’s relationship with his creature is deeper and more mysterious than any mere hatred. Both Frankenstein and the creature believe they have rejected each other, yet they also half understand that they are not merely complicit with each other, but that in some deep and obscure way they are indivisible. They are joined in a passionate wish to destroy anyone who might break through their shared isolation. The creature responds to Frankenstein’s rejection by committing violent acts of revenge, yet he takes his revenge not on Victor himself, but on Victor’s family and friends and the foster sister who hopes to marry him. Victor perceives that his creature is the means by which his own spirit kills those whom he believes he loves: “I considered the being whom I had cast among mankind, and endowed with the will and power to effect purposes of horror, . . . nearly in the light of my own vampire, my own spirit let loose from the grave, and forced to destroy all that was dear to me.” What Victor fails to perceive is that his family and friends—all those who want affection from him—are not dear to him at all. When he withdrew into the solitude of his laboratory, he also withdrew from everyone who wanted his love, and the creature, as if fulfilling a wish too dark for Frankenstein to see in himself, proceeds to destroy them all.

The creature never becomes, as a child does, an autonomous being. In a mysterious but inescapable way he is a hidden aspect of Frankenstein himself that has suddenly taken visible form. Victor’s friends, siblings, and parents all assume that he feels as close to them as they feel to him, but Victor’s only real relationship is with a monstrous emanation of himself. By the end of the book, he and his creature have withdrawn from all human society and made their way toward the frozen isolation of the North Pole in pursuit of one another. When Frankenstein at last dies—despite the creature’s secret efforts to keep him alive—the creature has nothing more to live for, and rushes away toward his own death. The fruits of the solitary act of ambition, not love, through which Victor gave life to his creature are a deepening solitude, murder, and self-destruction.

Everything Has a Beginning

Mary Shelley’s story of how Frankenstein came to be written has some of the drama and depth of the novel itself. She wrote an introduction to a revised third edition in 1831—the original version appeared in 1818 and was reprinted in 1823—in which she recalled the journey to Switzerland that she and Percy Bysshe Shelley made in 1816, when she was not yet nineteen. Their neighbor near Geneva was Lord Byron, who was there with his friend John William Polidori. After the four read some ghost stories, Byron decreed that they each would write a ghost story of their own. The three men immediately began writing their stories, and almost as immediately abandoned them. In contrast, Mary Shelley tried for some days to think of a story but could not, until one evening she heard Shelley and Byron talk about the possibility of reanimating a corpse, or of giving life to a body made up of separately manufactured parts. In bed that night, she suddenly saw in her imagination the scene in which Victor brings the creature to life, and the next morning she began writing the episode itself, beginning, “It was a dreary night in November . . .”

Other evidence suggests that Mary Shelley was retroactively improving on real events when she made so sharp a distinction between her slow patient start on her story and the quick impatience of her husband and friends, but her account points toward the themes that she knew she had woven into her novel. As she describes the events, she alone, unlike the three men in the party, brooded for days while awaiting the arrival of her story—the only one of the stories that grew into something finished and complete. “‘Have you thought of a story?’ I was asked each morning, and each morning I was forced to reply with a mortifying negative.” In the next sentence of her recollections, she generalizes: “Every thing must have a beginning . . . and that beginning must be linked to something that went before.” In Frankenstein the disasters that result from the beginning of the creature’s story are linked to the events that preceded it. The miseries of the creature’s life are inseparable from the way in which he was brought into life, and inseparable from his creator’s conscious and unconscious attitudes toward what Victor calls “generation and life.”

Mary Shelley gave Frankenstein its unique power by portraying its grotesque horrors as the consequence of the most familiar and ordinary causes. The whole moral and emotional content of her book is an extended restatement of a single sentence by her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, in the first feminist manifesto written in English, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792): “A great proportion of the misery that wanders, in hideous forms, around the world, is allowed to rise from the negligence of parents.” In ordinary life, these hideous forms are concealed behind everyday faces. In Frankenstein they appear as they are, in all their horror. The hideousness of Victor Frankenstein’s negligence of his creature is visible on the face of the creature itself as it wanders in hideous form around the world, inflicting and experiencing misery.

In lesser fictions of horror than Mary Shelley’s book, the startling monstrosity erupts into the world from a remote laboratory on a mountain peak. In Frankenstein the monstrosity emerges from an extreme version of the sort of emotional negligence that anyone might commit. The book invites its readers to recognize themselves in its hero. Almost all film and stage versions of Frankenstein portray horrors more spectacular but less unsettling than the book’s, because the adaptations portray Frankenstein as absolutely different from ourselves—either a deranged scientist with an unlimited equipment budget or the rich nobleman Baron von Frankenstein, never the Victor portrayed by Mary Shelley, the child of loving parents who grows up to be a dedicated but otherwise ordinary student living in rented rooms near the university, who improvises a laboratory of his own, as every chemistry student did, because universities did not yet provide one.* The filmed versions of Frankenstein omit everything in the book that insists that Victor is an extreme case of someone to whom intimacy and obligation are intolerable—as they sometimes are to everyone.

Parents: Maternal and Otherwise

No greater book than Frankenstein has been written by an author who was not yet twenty years old, and this novel, more than Mary Shelley’s later ones, combines the inchoate fears of childhood with the sophisticated intelligence of an adult. The fears that pervade the book are those of abandonment and death. Mary Shelley’s mother died a few days after giving birth to her. At the time Mary finished writing Frankenstein, in 1817, she had abandoned her father in the middle of the night to elope with her lover; she had given birth to a daughter (who died a few days later) and a son; and she was now pregnant for a third time.† The children’s father was Percy Bysshe Shelley, who abandoned his year-old child by his wife Harriet Westbrook when he and Mary eloped; Harriet was five months pregnant with their second child at the time. While

* Victor as mad scientist is a twentieth-century invention. In the nineteenth century he was always referred to as a student, as in Charles Dickens’s allusion in Great Expectations (1860-61) to “the imaginary student pursued by the misshapen creature he had impiously made.”

† The living son, William, died two years later at the age of three. Mary’s third child was a daughter, Clara, who lived only a year. Her fourth child, Percy Florence, born a year later, was her only child who survived her.

the book was being written, Mary’s half sister Fanny Imlay ran away from home, disguised her identity, and killed herself; two months later, Harriet killed herself, and was found to have been pregnant with a third child (the unknown father was possibly Percy himself, who could have encountered Harriet after he and Mary returned to London); Percy and Mary married soon afterward. Mary Shelley’s critics have pointed to one or another of these experiences as the key to Frankenstein, but all that seems certain is that the young Mary Shelley learned about many different ways in which parents and children can be divided from each other in both death and life, about many different kinds of physical and emotional estrangement.

Her book dramatizes the emotional horror of separation while analyzing it in moral terms. Victor Frankenstein explains away the murderous disasters by placing all the blame on destiny and fate—and Mary Shelley emphasized his evasion by making it even more prominent in the heavily revised third edition of the book of 1831 than it was in the first and second editions of 1818 and 1823. But she knew that Frankenstein’s claim to be the victim of malign impersonal forces is a way of evading responsibility, just as his isolated act of creation is a way of escaping intimacy.* Mary Shelley’s father, the radical political philosopher William Godwin, had emphasized the ways in which human beings are shaped by the impersonal forces of their environment. Mary Shelley admired her father enough to dedicate Frankenstein to him, but she was chilled by his fury over her elopement with Percy Bysshe Shelley and by

* Mary Shelley’s journals show that she herself was tempted to imagine that sufferings were required by fate. Writing in 1839, she interpreted the suicide of Shelley’s abandoned wife Harriet, many years earlier, as the event to which “I attribute so many of my own heavy sorrows, as the atonement claimed by fate for her death.” When she portrayed Victor Frankenstein making excuses for himself in attributing his sorrows to fate, she was both portraying and resisting a temptation of her own.

the cruelty of his refusals to sympathize over the deaths of her children. Victor Frankenstein’s isolating evasions are, among other things, her oblique criticism of her father’s evasions.

All the characters in her book take one of two opposite approaches to human relations. Either, like Victor Frankenstein, they flee from all mutual relations; or, like almost everyone else, they seek out those whom they can love and help, and, whether they are men or women, they act and live maternally. When Victor Frankenstein suffers a nervous collapse on the morning after he gives life to his creature, Victor’s friend Henry Clerval, having just arrived on the scene, tends him through his long illness. “He knew,” Frankenstein recalls of Clerval, “that I could not have had a more kind and a...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherPantheon

- Publication date2006

- ISBN 10 0375424083

- ISBN 13 9780375424083

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages288

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Things That Matter: What Seven Classic Novels Have to Say About the Stages of Life

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0375424083

The Things That Matter: What Seven Classic Novels Have to Say About the Stages of Life

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0375424083

The Things That Matter: What Seven Classic Novels Have to Say About the Stages of Life

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0375424083

THE THINGS THAT MATTER: WHAT SEV

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.95. Seller Inventory # Q-0375424083

The Things That Matter: What Seven Classic Novels Have to Say About the Stages of Life

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0375424083