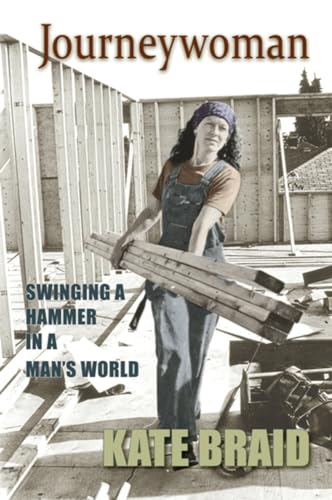

Journeywoman: Swinging a Hammer in a Man's World - Softcover

In 1977 when Braid was broke and out of work, her male friends encouraged her to apply as a labourer on a construction site on Pender Island, off the coast of British Columbia. She'd never heard of a woman doing this kind of work, but she was hired because (she later found out) the boss hoped that a woman onsite would improve the men's performance. For the next fifteen years Braid worked as a labourer, apprentice and journeywoman carpenter, building houses, bridges and high-rises. She was one of the first qualified women carpenters in British Columbia, the first woman to join the Vancouver local of the Carpenters' Union, the first to teach construction full-time at the BC Institute of Technology and one of the first women to run her own construction company. Though she loved the work, it was not an easy career choice but slowly she carved a role for herself, asking first herself, then those who would challenge her, why shouldn't a woman be a carpenter?

Told with humour, compassion and courage, Journey Woman is the true story of a groundbreaking woman finding success in a male-dominated field.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

“Watch out!”

Someone jerks my arm―hard―and as I catch myself, I glimpse Janet’s mouth shaped into a perfect soundless scream. Beside her, the forklift operator screeches to a halt, his back tire inches from me. His face mimes surprise and apology as Tom lets go of my arm and gestures for me to flip up my brand new ear muffs. I can hardly hear over the screech of saws.

“Watch out for the forklift!”

I nod, shaken, as Tom carries on, pointing up to where a set of rattling black chains, wide as a bed, divides above us. I feel thunder in my chest―the clash and groan of metal, scrape of lumber, howl of saws―and a smell so sharp and strong, it’s like walking through Buckley’s Cough Medicine. Soon, I’ll learn it’s the smell of thousands of board feet of freshly cut lumber.

“Grade A material,” Tom is screaming into my exposed ear, “stays up top!” He waves at a guy pushing buttons on a machine above us and to our left. I order myself to pay attention; he’s telling us how to do this job. “Rejects down here!” A small white feminine hand appears out of the plywood shack above us and to our right. “Grader’s shack!” Tom screams. The hand pushes logs off the top chain down to the lower one, where they fall in a clatter in front of Janet and me. Our job will be to pile these rejects on carts so the forklift can load them into boxcars.

This should be easy.

Janet and I had met a few months earlier, at an International Women’s Day celebration in Vancouver. When someone had asked about my plans for fall, I said I wanted to go back to university and for that, I needed a chunk of money, fast. When they asked, “How are you going to get it?” I said, “Up north.” Actually, until the words came out of my mouth, I had no plan at all, but in 1975, whenever a guy wanted money in British Columbia, he went “up north”―to Kitimat, Smithers, Prince George―and came back with pocketfuls. It was boom days in northern BC; trees were being cut as fast as loggers could topple them, and dams, roads, mills, whole towns were popping up. If a man could earn big money up north, I suddenly thought, why couldn’t I?

A British accent over my left shoulder chimed, “Me too.” It was Janet, and I was in luck. She’d taught in BC’s north for two years, and exotic words like Telkwa, Nass, Kitwanga, now rippled off her tongue as she told me the names of people she knew, places we could stay. Best of all, the words included places we might work. “Sawmill,” she said. “Fish plant. Pulp mill.” It never crossed my mind to ask if they hired women in sawmills. Instead, I phoned my mum and dad to tell them I was going north this summer to work. I was vague about the details.

We shopped at an army surplus store on East Broadway for what Janet called “necessities”: plates, cutlery, a wallet-sized silver blanket (“Developed by NASA for Outer Space!”), sleeping bags, steel-toed boots and, for me, an ancient Trapper Nelson pack, the kind made of green canvas with a wood frame and leather straps. A few weeks later, Trapper Nelson at my side, Janet and I were standing at the on-ramp to Highway 1 with our thumbs out.

The world looks bigger from the back of a pickup truck. Heading east from Vancouver, past the town of Hope, then north, the country was no longer the steep up-and-down, brilliant greens of the west coast; it was long flat rolling hills, soft browns and the smell of something sweet.

“Sage,” Janet said.

The pickup dropped us in downtown Williams Lake. I was busy ogling store windows full of cowboy boots and Stetson hats―as foreign as haute couture in Paris―when an old man walked by.

“Howdy.”

They even spoke a foreign language. There was a sawmill in this town, and Janet used the restaurant phone to ask if they needed any help. Her face told me the answer. We picked up our packs, headed back to the highway, and for the next two weeks applied at every sawmill, paper mill and fish processing plant between Williams Lake and Prince Rupert. After twenty-eight years of living in cities and working in offices, it felt odd to talk to bosses called foremen who wore blue jeans instead of a suit. After each foreman took one look and said, “Sorry, girls,” we moved on to the next. But when we got to Prince Rupert, to the coast, we’d turned around and started back toward Prince George in the diminishing hope that we’d somehow missed a place, that one of those foremen might change his mind. So far we’d only spent money, and it was almost June.

Finally, a truck driver told us he’d heard Canadian National Rail was hiring line crew at Hazelton, to lay track. We had no idea what “laying track” meant, but by now we were desperate. The trucker let us off at the Hazelton exit and pointed north. Janet and I walked up a gravel track and reached a trailer marked CNR just as a man pulling on his baseball cap stepped outside. As he brushed past he said amiably, “Looking for work, girls?”

“Yes.”

That stopped him. As we shook hands it was suddenly all I could do not to turn and run. It felt weird to be standing outside while we talked about work, and what if this wild plan was about to actually become real? The foreman said he’d never hired a woman before, and even if he wanted to, he had no accommodation for us. When Janet prompted him, “You can put us in with the cooks,” he pulled the brim of his cap back and forth across his forehead a few times, then gave us an even look.

“You know what this job is, don’t you?”

We had no idea and he knew it, so he told us. We’d be going miles into the bush to tear up and lay down track and would be gone two, three weeks―us and a train full of men. He finished, “You’ll wreck your hands.”

But this was the only job we’d had even a whiff of and I was into it now. I boasted we were strong, we’d get stronger, we’d wear gloves.... He said he’d think about it and told us to meet him at 4:30 in the pub. We waited until 5:00, hoping the beer might soften him up.

“No.”

“Why not?”

“The cooks you’re so eager to stay with are pushing fifty and can upend a drunken road hand better than I can. I won’t take two young women out into the bush with a crew of rangytangs because once the boys get into the liquor I’ll end up spending my nights camped in front of your door with a rifle across my knees.”

That did it for me, but Janet fired a last volley, threatening to go to the Canadian Human Rights Commission, like the women who’d just launched a law suit against CN in Quebec for exactly this reason.

“Sue me,” he said kindly. “I won’t hire you.”

And that was it. We both knew there was virtually no chance of finding work before we reached Prince George that evening, and in that case, we might as well go home. A few rides later, less than seventy miles before Prince George, an Indo–Canadian couple with a child in the back seat picked us up. It was the woman who said, “There’s work at the mill in Fort St. James.” She knew because she used to work there herself. Her name was Parminder, and that night we squeezed into the spare bedroom in her family’s tiny trailer.

The next morning, Janet marched ahead of me across a huge parking lot filled with cut lumber and whole logs and that Buckley’s smell toward a small trailer with the sign Apollo Forest Products above its door, where a man behind a desk told us yes, he needed people for work in his planer mill, starting immediately.

“Pays $5.25 an hour.”

Janet and I were both nodding as he handed us each a pair of leather gloves, a red hard hat and a set of yellow ear muffs. The last job I’d had―one of those federal Opportunities for Youth jobs that kept unemployed young people off welfare―paid $3.

The man’s name was Archie and he was the owner. The hard hat felt rigid and unbalanced, as if someone had plopped a cardboard box on my forehead. Archie showed us how to attach the muffs, calling them “Mickey Mouse ears,” then led us across the yard to a low industrial building with corrugated metal sides. When he opened a side door, the screech of metal made us clutch at our ears as he pointed furiously at our heads.

“Ear muffs!”

We pulled them down awkwardly but lifted them again so he could scream, “Tom! Your foreman!” when a small man with a blue hard hat, muffs up, appeared before us.

Tom led Janet and me inside, along the long arm of the double chain that ground and screeched as sticks of wood bobbed over it like logs on water. I caught a glimpse of men with their backs to us, monster saws, then a sharp right to where a railway car sat open to our left, half-packed with lumber. It all felt surreal, bigger than it should be, as if―like Alice into Wonderland―stepping through the door of the mill had changed everything.

Now, after saving me from the forklift, Tom picks a piece of wood off the chain to show us the blue scribble on its end.

“Grader marking! Too short! A reject!” He fires it onto one of the carts lined up beside the chain and instantly grabs another. “Bark!” A log with tree bark still showing on one side and a different scribble that he fires onto a second cart.

The carts are metal beds on wheels with a wall at the back, and the thonk! of wood against steel adds to the din. He wants us to pile these rejects, each on the right cart depending on its scribble, dividing the layers with spacers―“Suckers!” he yells in my ear, and for a second I think he’s referring to Janet and me. Then, nodding for Janet to stand at the front of this section and me at the back, he gives us a thumbs-up and is gone.

I spent years learning to type sixty words a minute, but any time I ever applied for a secretarial job, they took me into an airless cell, told me to relax and gave me a typing test as if to catch me lying. Here, Archie is willing to pay Janet and me more money than we’ve ever made, to do something we’ve never done before, and he hasn’t even asked if we know a tree from a tea cup.

Gingerly, I lift the first log―stick? what are they called?―and check the blue mark. The gloves Archie gave us are too big. My new boots weigh a ton. And then I forget everything, concentrating on getting the logs to go where I want them. One at a time. Carefully. My watch must have stopped, because surely it’s more than thirty minutes later when I notice that the back end of the chain―my end―is packed full of wood, three and four pieces deep, while it continues to fall in an alarming blue and yellow torrent at Janet’s end. I wave at her, point at the pile. Janet wiggles at her ear with her too-large glove and mouths the word, “Damn.” We both bend forward, working harder. But we can’t catch up. Hardly any of the logs are going up top, where the machine piles them; they’re all getting pushed down here by that little white hand, all rejects. Janet and I keep forgetting which mark goes where. The wood won’t lie straight. I get my pieces crossed with Janet’s, and once a cart is almost full, it’s so hard to get the last pieces to the top. Suddenly, with a long scream, the whole chain grinds to a halt.

In the shocking silence, I catch sight of Janet, the top of her head bizarrely swollen by the red hard hat, bulging bug eyes between the bright yellow ears, her face sweaty and red. I look like that, too, I think, as Tom flies around the corner, frowning. When he sees the chain, he grins. I giggle. Then I’m laughing, or maybe crying. Tears pour down my face, mixed with sweat. We’ve found the only job for us in the entire north, and we’re about to be fired after less than an hour! It’s hilarious! I wonder if I’m hysterical.

“Let’s get this moving,” Tom calls into the strange calm of the mill. He works with astonishing speed to help us pile, and in no time every piece of wood is on its wagon and the wild clanking of the chain starts again.

When the lunch horn sounds, I’m amazed at how tired my arms and legs suddenly feel. We follow the others to a narrow shack in the centre of the mill where we sit on wooden benches at a plywood table worn dark by use and where the walls are papered with posters warning blood if we don’t follow safety procedures. Last one into the shack is a short woman with dark hair who introduces herself as Dean, the lumber grader. Dean introduces the others: Cowboy, the forklift operator, who keeps his eyes firmly on the table; Wayne, the man on the chain above us; and a man with bright red hair who introduces himself as Brian.

“I run the front-end loader.”

Dean seems to feel Janet and I have imported women’s liberation into the north. “Now we’ll show these men a thing or two!” she boasts. But I’m afraid I’m going to disappoint her. I feel an unfamiliar, primal urge to guard my energy, waste nothing on conversation. As I walk back to my place on the chain, my arms swing like two sticks from the rigid pole that’s all that’s left of my shoulders. Four and a half hours to go.

A quarter to five is the moment when I think I’ll die. If I don’t die, I’ll throw up. My arms and legs scream to stop. Fifteen minutes more, I promise them. I put my head down and heave, pushing one log at a time, toward five.

Then an angel with red hair appears.

“I’ve finished loading!” Brian mouths, but I barely glance at him. Seeing he knows how it’s done, I only pretend to move my leaden arms while Brian piles the remaining wood.

As the quitting bell rings I say out loud, “I never knew there were so many logs.”

“Boards,” Brian says. I can hear him. They’ve turned the chain off. It’s ecstasy to stand still.

Every morning for a week, I wake up stiff in a new part of my body, but I love this work. Janet and I get up at 6:45, pull on blue jeans and T-shirts, wash our faces, eat, fill the thermoses we bought at Fields in town, pack lunch and leather gloves into our daypacks, pick up our hard hats and stand out on the highway to hitch to work by eight. Work on the planer chain starts awkwardly every time, but after an hour or so, I get into the rhythm. Turn, bend, pull; turn, bend, pull. If I use the boards’ own momentum, I only have to guide them into place, like obedient dogs on a short leash. By week two, my body feels slim and strong, and I hardly ever have to stop to remember what each blue mark means. One morning when I pile two boards at once, it feels so good that I laugh out loud.

We continue to stay with Parminder, who is wonderfully generous. Janet and I chip in for groceries but Parminder insists on doing most of the shopping and all of the cooking, welcoming us home every afternoon from work. She misses the company of the planer mill, she tells us, and is eager to hear news. However, her husband is clearly not as happy with houseguests, so Janet and I start looking for our own place. Accommodation is scarce in the Fort, and eventually it’s Brian who tells us a friend of his has just dragged an old cabin out of the woods and will let us live there rent-free for the rest of the summer.

When he drives us over the following Saturday to check it out, it’s clear that when he said “cabin,” he was speaking loosely. This one has four bare wood walls, a roof and a rough counter inside the back door with a shelf above. That’s it. There’s no furniture, no drywall, no windows (at least none with glass). No door. From inside, you can see daylight through the...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherCaitlin Press Inc.

- Publication date2012

- ISBN 10 1894759877

- ISBN 13 9781894759878

- BindingPaperback

- Edition number1

- Number of pages272

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Journeywoman: Swinging a Hammer in a Man's World

Book Description Softcover. Condition: New. First Edition. Since women started working in the trades in the 1970s, very little has been published about their experiences. In this provocative and important book, Kate Braid tells the story of how she became a carpenter in the face of skepticism and discouragement.In 1977 when Braid was broke and out of work, her male friends encouraged her to apply as a labourer on a construction site on Pender Island, off the coast of British Columbia. She'd never heard of a woman doing this kind of work, but she was hired because (she later found out) the boss hoped that a woman onsite would improve the men's performance. For the next fifteen years Braid worked as a labourer, apprentice and journeywoman carpenter, building houses, bridges and high-rises. She was one of the first qualified women carpenters in British Columbia, the first woman to join the Vancouver local of the Carpenters' Union, the first to teach construction full-time at the BC Institute of Technology and one of the first women to run her own construction company. Though she loved the work, it was not an easy career choice but slowly she carved a role for herself, asking first herself, then those who would challenge her, why shouldn't a woman be a carpenter?Told with humour, compassion and courage, Journey Woman is the true story of a groundbreaking woman finding success in a male-dominated field. Seller Inventory # DADAX1894759877

Journeywoman: Swinging a Hammer in a Man's World

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. 0.9. Seller Inventory # 1894759877-2-1