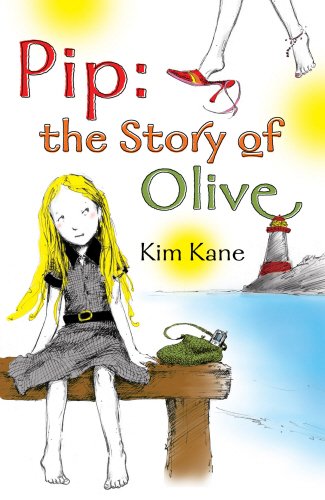

Pip: The Story of Olive - Softcover

Rare Book

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

Kim Kane was born in London in a bed bequeathed by Wordsworth for “. . . a writer, a dancer, or a poet.” Despite this auspicious beginning, she went on to practise law. In 2004, Kim threw her unbridled materialism to the wind and started to write. Kim now works exactly part-time as a lawyer and exactly part-time as a writer, and the combination is perfect. Pip: The Story of Olive is Kim’s first novel. Writing it very nearly killed her.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

Chicken Loaf and Chaos

Olive Garnaut looked ever so slightly like an extraterrestrial: a very pale extraterrestrial. She had long thin hair, which hung and swung, and a long thin face to match it. Her eyes were pale green and so widely spaced that if she looked out of the corners of them she could actually see her plaits banging against her bottom.

Olive’s eyelashes and eyebrows were so very fair that they blended right into her forehead and people could only spot them if the sun caught her at a strange angle. When she stood, her feet turned out at one hundred and sixty degrees (like a ballerina in first position), and her shins were the exact colour of chicken loaf.

It went without saying that Olive was the most peculiar-looking girl in Year 7. But what happened to Olive Garnaut was not because she looked ever so slightly like an extraterrestrial, even a very pale one.

‘Yer mum go and bleach yer, did she?’ said the baker every time Olive went to buy buns. ‘Those arms’d burn in two minutes at the beach.’ The baker always laughed and Olive always flushed puce to her hair roots.

Olive liked to buy buns six at a time, even though she knew that five would probably be tossed into the compost after they had gone splotchy in the breadbin. Olive liked the baker to think that she might just be collecting buns to take home to a family full of children and noise, a family like Mathilda Graham’s.

‘Mrs Graham doesn’t buy her buns, she bakes them, and she certainly doesn’t let them go green in the breadbin,’ Olive would mutter near Mog.

‘How else would penicillin have been invented?’ Mog would respond (nursing a gin-and-tonic headache and willing to embrace mould). Mog was Olive’s mum, and Olive called her Mog because that’s the sort of family they were. But Olive called her ‘Mum’ at school — the same way she sometimes made her own sandwiches, rather than buying them from the tuckshop, and then pretended that Mog had prepared them instead. Olive would say, rather too loudly, ‘Gross, Mum’s given me cheese ’n’ gherkin spread again.’ Nobody took much notice — except Mathilda, who knew but didn’t say anything. Mathilda Graham was Olive’s best friend. Olive liked Mathilda; Mathilda liked tuck lunches.

Mathilda was one of the only friends Olive had ever brought home. Olive lived ‘out in the sticks’ (or so Mathilda’s mum grumbled when she dropped Olive off). While Mathilda could walk to school, Olive faced a three-tram ride or a taxi. But it wasn’t just distance that made Olive reluctant to bring anybody home.

Olive and Mog rattled around in a ramshackle house with five bedrooms, a drawing room, a sitting room, a morning room, two studies, a billiard room, a cellar, a scullery and a room with no name that had bars on the windows because the family before them had collected stamps. The house was right near the sea and was Federation in style, which meant that it was built when Australia became a nation of states and women wore whalebone in their singlets to make them look thin. Mog always complained that it hadn’t been touched since.

Mog liked the idea of living in a magazine house, but she didn’t have the time to be neat or the patience for interior decorators. ‘This home may look as weary as I feel, but it’s got good bones,’ she’d say. ‘Besides, I have better things to do with my time than discuss whether the kitchen would look more “of the minute” painted in butter-yellow or clotted milk.’

Olive rather fancied the idea of their house with butter-yellow or clotted-milk walls. It would be like living in a cream tea, she thought. It could only be better than cobwebs and stains.

While Mog did not have time for interior decorators, she did have time to look in junk shops. On special weekends, when Mog wasn’t working, Olive and Mog travelled through the country in a hire car with a driver, trawling through second-hand shops, eating tarts and searching for gems with jammy fingers. Mog swore that she would strip the gems and turn them into something new and stylish, but they both knew, somewhere not too deep down, that she never would. Consequently, Mog and Olive had a real Colonial fridge with torn flywire; a ‘Leading Lady’ hairdryer; seventies dolls with nipped waists; and champagne saucers with bubbled glass, which they always meant to stack into a pyramid just like in an old Grace Kelly movie.

Perhaps their most beautiful find was the Brass Eye — an antique marble, about the size of a bubblegum ball, tucked into the tip of a hollow metal stem. It was slightly longer than a lipstick and looked like a tiny squat telescope. Mog and Olive had bought it in a shop on the goldfields from a man with a tic that made him wink.

Olive kept all the golden bits on the Brass Eye polished with Brasso and an old tennis sock. It rattled as she rubbed it. When Olive looked through the stem of the Brass Eye, the light refracted and everything appeared in triangles and circles. If she moved towards an object, Olive could see it spliced into hundreds of pieces; if she moved away, the object shot outwards, exploding from pinpoints like choreographed fireworks or synchronized swimmers. Olive liked to point the Brass Eye at her shoes and watch as her T-bars doubled, quadrupled and then octupled while she pulled back slowly, until they finally ignited in a dazzling jumble of school socks and silver buckles.

‘But how does it work?’ Olive asked Mog again and again.

‘It’s all smoke and mirrors, Ol,’ Mog said. And, as a child, Olive had imagined that the stem of the Brass Eye rattled because it was filled with tiny mirrors and little Indians who burned wet matchsticks and wafted smoke along the brass tube; brassy smoke to multiply Olive’s school socks and T-bar shoes.

Unfortunately, not everything was as beautiful as the Brass Eye. When Mog and Olive returned home from their junk-hunts, Mog would put the stuff down wherever there was space — and there it would usually stay. Much to Olive’s shame, the house was crowded with mountains of knick-knacks and clutter that lined the hall and cast shadows in dank piles. The piles were so high in places that she couldn’t see over them, and the dust made her wheeze. Nobody at school had to live in bedlam like that.

‘Mog, this chaos is deesgusting,’ Olive would say, working her way through the mess; tick-tack-toeing along record covers.

‘Chaos is merely order waiting to be decoded,’ Mog would respond.

‘Mrs Graham says that an untidy house shows an untidy mind,’ Olive would shoot back (but only ever in a whisper). As a consequence of the mess, Olive stuck to her bedroom and the kitchen — which she always kept clutter-free and tidy-minded.

Olive liked her bedroom symmetrical. She liked things in pairs. She had two beds with matching duvets; two lampshades with sage velvet trim; and two bedside tables, each with its own box of tissues and a copy of Anne of Green Gables. Around the walls, Olive had strung chains of paper dolls holding hands. They were meant to look like the French schoolgirls in the Madeline books, but Olive didn’t have a navy felt tip, so their coats were red. To make the dolls, Olive had folded the butcher’s paper carefully down the centre to ensure that their heads and hats were exactly even. Two perfect halves.

Olive believed that everything had two perfect halves — that halves were somehow essential, oats in the porridge of life. In the body, for example, there are two eyes, two ears, two feet, two hands, two kidneys. Even tricky things like the nose and mouth are really comprised of twos (two nostrils, two rows of teeth). It wasn’t something that Olive worried about or even discussed; just something that she had noticed ever since she’d discovered she was born at 2.22 a.m. on the second of February, weighing in at a tiny 2.2 kilograms.

‘Cosmic,’ WilliamPetersMustardSeed had responded (well, so Mog reported after two too many wines one night). ‘We should give her a two-syllable name,’ he had added, before passing out on his second celebratory joint. Mog, awash with hormones, had obligingly called the fledgling ‘O-live’. Unfortunately, Mog had packed her bags a fortnight later when WilliamPetersMustardSeed shacked up with another woman, leaving Olive, Mog and their two-by-one family.

But even with a perfectly symmetrical family, body and bedroom, there was always something absent with Olive — she had only ever felt half. She didn’t feel half from her waist down or from her waist up; it was more abstract than that. ‘Is the glass half full or half empty?’ Mog always asked. Half full/half empty was Mog’s test for whether a person was a pessimist or an optimist.

Mog was a half-full, sunny type of woman, even though the house was messy and she’d had to become a barrister because life hadn’t dealt her the hand she’d expected. But to Olive it didn’t really matter: half full or half empty, there was still a lot missing.

What happened to Olive, however, wasn’t because she’d only ever felt half. It didn’t even happen because her house was full of knick-knacks and clutter, because she called her mother Mog, or because she knew of a man named WilliamPetersMustardSeed. It wasn’t because she had a peculiar relationship with the number two, or because her skin was the exact colour of chicken loaf. Although there was never any doubt that it was a shake-it-all-about hokey-pokey of all these things, what happened to Olive couldn’t have happened without Mathilda Graham.

Olive Garnaut looked ever so slightly like an extraterrestrial: a very pale extraterrestrial. She had long thin hair, which hung and swung, and a long thin face to match it. Her eyes were pale green and so widely spaced that if she looked out of the corners of them she could actually see her plaits banging against her bottom.

Olive’s eyelashes and eyebrows were so very fair that they blended right into her forehead and people could only spot them if the sun caught her at a strange angle. When she stood, her feet turned out at one hundred and sixty degrees (like a ballerina in first position), and her shins were the exact colour of chicken loaf.

It went without saying that Olive was the most peculiar-looking girl in Year 7. But what happened to Olive Garnaut was not because she looked ever so slightly like an extraterrestrial, even a very pale one.

‘Yer mum go and bleach yer, did she?’ said the baker every time Olive went to buy buns. ‘Those arms’d burn in two minutes at the beach.’ The baker always laughed and Olive always flushed puce to her hair roots.

Olive liked to buy buns six at a time, even though she knew that five would probably be tossed into the compost after they had gone splotchy in the breadbin. Olive liked the baker to think that she might just be collecting buns to take home to a family full of children and noise, a family like Mathilda Graham’s.

‘Mrs Graham doesn’t buy her buns, she bakes them, and she certainly doesn’t let them go green in the breadbin,’ Olive would mutter near Mog.

‘How else would penicillin have been invented?’ Mog would respond (nursing a gin-and-tonic headache and willing to embrace mould). Mog was Olive’s mum, and Olive called her Mog because that’s the sort of family they were. But Olive called her ‘Mum’ at school — the same way she sometimes made her own sandwiches, rather than buying them from the tuckshop, and then pretended that Mog had prepared them instead. Olive would say, rather too loudly, ‘Gross, Mum’s given me cheese ’n’ gherkin spread again.’ Nobody took much notice — except Mathilda, who knew but didn’t say anything. Mathilda Graham was Olive’s best friend. Olive liked Mathilda; Mathilda liked tuck lunches.

Mathilda was one of the only friends Olive had ever brought home. Olive lived ‘out in the sticks’ (or so Mathilda’s mum grumbled when she dropped Olive off). While Mathilda could walk to school, Olive faced a three-tram ride or a taxi. But it wasn’t just distance that made Olive reluctant to bring anybody home.

Olive and Mog rattled around in a ramshackle house with five bedrooms, a drawing room, a sitting room, a morning room, two studies, a billiard room, a cellar, a scullery and a room with no name that had bars on the windows because the family before them had collected stamps. The house was right near the sea and was Federation in style, which meant that it was built when Australia became a nation of states and women wore whalebone in their singlets to make them look thin. Mog always complained that it hadn’t been touched since.

Mog liked the idea of living in a magazine house, but she didn’t have the time to be neat or the patience for interior decorators. ‘This home may look as weary as I feel, but it’s got good bones,’ she’d say. ‘Besides, I have better things to do with my time than discuss whether the kitchen would look more “of the minute” painted in butter-yellow or clotted milk.’

Olive rather fancied the idea of their house with butter-yellow or clotted-milk walls. It would be like living in a cream tea, she thought. It could only be better than cobwebs and stains.

While Mog did not have time for interior decorators, she did have time to look in junk shops. On special weekends, when Mog wasn’t working, Olive and Mog travelled through the country in a hire car with a driver, trawling through second-hand shops, eating tarts and searching for gems with jammy fingers. Mog swore that she would strip the gems and turn them into something new and stylish, but they both knew, somewhere not too deep down, that she never would. Consequently, Mog and Olive had a real Colonial fridge with torn flywire; a ‘Leading Lady’ hairdryer; seventies dolls with nipped waists; and champagne saucers with bubbled glass, which they always meant to stack into a pyramid just like in an old Grace Kelly movie.

Perhaps their most beautiful find was the Brass Eye — an antique marble, about the size of a bubblegum ball, tucked into the tip of a hollow metal stem. It was slightly longer than a lipstick and looked like a tiny squat telescope. Mog and Olive had bought it in a shop on the goldfields from a man with a tic that made him wink.

Olive kept all the golden bits on the Brass Eye polished with Brasso and an old tennis sock. It rattled as she rubbed it. When Olive looked through the stem of the Brass Eye, the light refracted and everything appeared in triangles and circles. If she moved towards an object, Olive could see it spliced into hundreds of pieces; if she moved away, the object shot outwards, exploding from pinpoints like choreographed fireworks or synchronized swimmers. Olive liked to point the Brass Eye at her shoes and watch as her T-bars doubled, quadrupled and then octupled while she pulled back slowly, until they finally ignited in a dazzling jumble of school socks and silver buckles.

‘But how does it work?’ Olive asked Mog again and again.

‘It’s all smoke and mirrors, Ol,’ Mog said. And, as a child, Olive had imagined that the stem of the Brass Eye rattled because it was filled with tiny mirrors and little Indians who burned wet matchsticks and wafted smoke along the brass tube; brassy smoke to multiply Olive’s school socks and T-bar shoes.

Unfortunately, not everything was as beautiful as the Brass Eye. When Mog and Olive returned home from their junk-hunts, Mog would put the stuff down wherever there was space — and there it would usually stay. Much to Olive’s shame, the house was crowded with mountains of knick-knacks and clutter that lined the hall and cast shadows in dank piles. The piles were so high in places that she couldn’t see over them, and the dust made her wheeze. Nobody at school had to live in bedlam like that.

‘Mog, this chaos is deesgusting,’ Olive would say, working her way through the mess; tick-tack-toeing along record covers.

‘Chaos is merely order waiting to be decoded,’ Mog would respond.

‘Mrs Graham says that an untidy house shows an untidy mind,’ Olive would shoot back (but only ever in a whisper). As a consequence of the mess, Olive stuck to her bedroom and the kitchen — which she always kept clutter-free and tidy-minded.

Olive liked her bedroom symmetrical. She liked things in pairs. She had two beds with matching duvets; two lampshades with sage velvet trim; and two bedside tables, each with its own box of tissues and a copy of Anne of Green Gables. Around the walls, Olive had strung chains of paper dolls holding hands. They were meant to look like the French schoolgirls in the Madeline books, but Olive didn’t have a navy felt tip, so their coats were red. To make the dolls, Olive had folded the butcher’s paper carefully down the centre to ensure that their heads and hats were exactly even. Two perfect halves.

Olive believed that everything had two perfect halves — that halves were somehow essential, oats in the porridge of life. In the body, for example, there are two eyes, two ears, two feet, two hands, two kidneys. Even tricky things like the nose and mouth are really comprised of twos (two nostrils, two rows of teeth). It wasn’t something that Olive worried about or even discussed; just something that she had noticed ever since she’d discovered she was born at 2.22 a.m. on the second of February, weighing in at a tiny 2.2 kilograms.

‘Cosmic,’ WilliamPetersMustardSeed had responded (well, so Mog reported after two too many wines one night). ‘We should give her a two-syllable name,’ he had added, before passing out on his second celebratory joint. Mog, awash with hormones, had obligingly called the fledgling ‘O-live’. Unfortunately, Mog had packed her bags a fortnight later when WilliamPetersMustardSeed shacked up with another woman, leaving Olive, Mog and their two-by-one family.

But even with a perfectly symmetrical family, body and bedroom, there was always something absent with Olive — she had only ever felt half. She didn’t feel half from her waist down or from her waist up; it was more abstract than that. ‘Is the glass half full or half empty?’ Mog always asked. Half full/half empty was Mog’s test for whether a person was a pessimist or an optimist.

Mog was a half-full, sunny type of woman, even though the house was messy and she’d had to become a barrister because life hadn’t dealt her the hand she’d expected. But to Olive it didn’t really matter: half full or half empty, there was still a lot missing.

What happened to Olive, however, wasn’t because she’d only ever felt half. It didn’t even happen because her house was full of knick-knacks and clutter, because she called her mother Mog, or because she knew of a man named WilliamPetersMustardSeed. It wasn’t because she had a peculiar relationship with the number two, or because her skin was the exact colour of chicken loaf. Although there was never any doubt that it was a shake-it-all-about hokey-pokey of all these things, what happened to Olive couldn’t have happened without Mathilda Graham.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherDavid Fickling Books

- Publication date2010

- ISBN 10 1849920028

- ISBN 13 9781849920025

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages256

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 2.67

Shipping:

US$ 31.56

From United Kingdom to U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Pip: the Story of Olive

Published by

David Fickling Books (PB)

(2010)

ISBN 10: 1849920028

ISBN 13: 9781849920025

New

Paperback

Quantity: 3

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # mon0000008183

Buy New

US$ 2.67

Convert currency