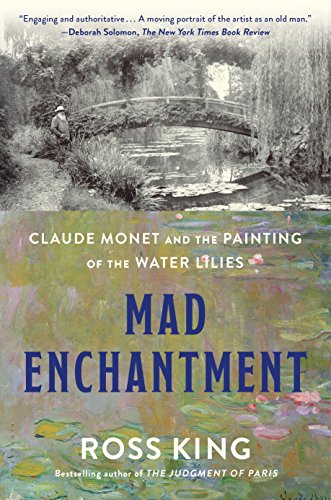

Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies - Softcover

From bestselling author Ross King, a brilliant portrait of the legendary artist and the story of his most memorable achievement.

Claude Monet is perhaps the world's most beloved artist, and among all his creations, the paintings of the water lilies in his garden at Giverny are most famous. Monet intended the water lilies to provide "an asylum of peaceful meditation." Yet, as Ross King reveals in his magisterial chronicle of both artist and masterpiece, these beautiful canvases belie the intense frustration Monet experienced in trying to capture the fugitive effects of light, water, and color. They also reflect the terrible personal torments Monet suffered in the last dozen years of his life.

Mad Enchantment tells the full story behind the creation of the Water Lilies, as the horrors of World War I came ever closer to Paris and Giverny and a new generation of younger artists, led by Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, were challenging the achievements of Impressionism. By early 1914, French newspapers were reporting that Monet, by then seventy-three, had retired his brushes. He had lost his beloved wife, Alice, and his eldest son, Jean. His famously acute vision--what Paul Cezanne called “the most prodigious eye in the history of painting”--was threatened by cataracts. And yet, despite ill health, self-doubt, and advancing age, Monet began painting again on a more ambitious scale than ever before. Linking great artistic achievement to the personal and historical dramas unfolding around it, Ross King presents the most intimate and revealing portrait of an iconic figure in world culture.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Recording the fugitive effects of color and light was integral to Monet’s art. Setting up his easel in front of Rouen Cathedral, or the wheat stacks in the frozen meadow outside Giverny, or the windswept cliffs at Étretat on the coast of Normandy, he would paint throughout the day as the light and weather, and finally the seasons, changed. To reproduce the desired effects accurately according to his personal sensations, he was forced to work outdoors, often in disagreeable conditions. In 1889 a journalist described him on the stormy beach beneath the cliffs at Étretat, “dripping wet under his cloak, painting a hurricane in the salty spray” as he tried to capture the different lighting conditions on two or three canvases that he shuttled back and forth onto his easel. Because lighting effects changed quickly—every seven minutes, he once claimed—he was forced, in his series paintings of wheat stacks and poplars, to work on multiple canvases almost simultaneously, placing a different one on his easel every seven minutes or so, rotating them according to the particular visual effect he was trying to capture. Clemenceau once watched him working in a poppy field with four different canvases. “He was going from one to the other, according to the position of the sun.” In the 1880s the writer Guy de Maupassant had likewise witnessed Monet “in pursuit of impressions” on the Normandy coast. He described how the painter was followed through the fields by his children and stepchildren “carrying his canvases, five or six paintings depicting the same subject at different times and with different effects. He worked on them one by one, following all the changes in the sky.” This obsession with capturing successive changes in the fall of light or the density of a fogbank could lead to episodes that were both comical (for observers) and infuriating (for Monet). In 1901, in London, he began painting what he called the “unique atmosphere” of the river Thames—the famous pea-souper fogs—from his room in the Savoy Hotel. Here he was visited by the painter John Singer Sargent, who found him surrounded by no fewer than ninety canvases, “each one the record of a momentary effect of light over the Thames. When the effect was repeated and an opportunity occurred for finishing the picture,” Sargent reported, “the effect had generally passed away before the particular canvas could be found.”

One irony of Monet’s approach was that these paintings of fleeting visual effects at single moments in time actually took many months of work. “I paint entirely out of doors,” he once airily informed a journalist. “I never touch my work in my studio.” However, virtually all of Monet’s canvases, although begun on the beaches or in the fields, were actually completed back in the studio, often far from the motif and with much teeth-gnashing labor. Octave Mirbeau reported that a single Monet canvas might take “sixty sessions” of work. Some of the canvases, moreover, were given fifteen layers of paint. His London paintings were finished not beside the banks of the Thames but as much as two years later in his studio in Giverny, beside the Seine, with the assistance of photographs. The revelation that Monet used photographs caused something of a scandal when this expedient was revealed in 1905 thanks to the indiscreet and possibly malicious comments of several of Monet’s London acquaintances, including Sargent. Monet had risked a similar kind of scandal when he took one of his Rouen Cathedral paintings to Norway.

There was another irony to Monet’s paintings. Many of them evoked gorgeous visions of rural tranquility: sun-dappled summer afternoons along a riverbank or fashionable women promenading in flowery meadows. As Mirbeau wrote, nature appeared in Monet’s paintings in “warm breaths of love” and “spasms of joy.” His pleasingly bucolic scenes were combined with a flickering brushwork that produced delicious vibrations of color. The overall result was that many observers regarded his paintings as possessing a soothing effect on both the eye and the brain—and Monet himself as le peintre du bonheur (the painter of happiness). Geffroy believed Monet’s works could offer comforting distraction and alleviate fatigue, while Monet himself speculated that they might calm “nerves strained through overwork” and offer the stressed out viewer “an asylum of peaceful meditation.” The writer Marcel Proust, an ardent admirer, even believed Monet’s paintings could play a spiritually curative role “analogous to that of psychotherapists with certain neurasthenics”—by which he meant those whose weakened nerves had left them at the mercy of fast-paced modern life. Proust was not alone. More than a century later, an Impressionist expert at Sotheby’s in London called Monet “the great anti-depressant.” This “great anti-depressant” was, however, a neurasthenic who enjoyed anything but peaceful meditation as he worked on his paintings. Geffroy described Monet as “a perpetual worrier, forever anguished,” while to Clemenceau he was le monstre and le roi des grincheux—“king of the grumps.” Monet could be volatile and bad-tempered at the best of times, but when work at his easel did not proceed to his satisfaction—lamentably often—he flew into long and terrible rages. Clemenceau neatly summed up the quintessential Monet scenario of the artist throwing a tantrum in the midst of blissful scenery: “I imagine you in a Niagara of rainbows,” he wrote to Monet, “picking a fight with the sun.” Monet’s letters are filled with references to his gloom and anger. Part of his problem was the weather. Monet could pick a fight with the sun, the wind, or the rain. Painting in the open air left him at the mercy of the elements, at which he raged like King Lear. His constant gripes about the wind and rain had once earned him a scolding from Mirbeau: “As for the nauseatingly horrible weather we have and that we will have until the end of August, you have the right to curse. But to believe that you’re finished as a painter because it’s raining and windy—this is pure madness.”

It was a strange contradiction of Monet’s practice that he wished to work in warm, calm, sunny conditions, and yet for much of his career he chose to paint in Normandy: a part of France that was, as a nineteenth-century guidebook glumly affirmed, “generally cold and wet...subject to rapid and frequent changes, and fairly long spells of bad weather that result in unseasonable temperatures.” Working on the windswept coast of Normandy in the spring of 1896, he found conditions exasperating. “Yesterday I thought I would go mad,” he wrote. “The wind blew away my canvases and, when I set down my palette to recover them, the wind blew it away too. I was so furious I almost threw everything away.” Sometimes Monet did in fact throw everything away. On one occasion he hurled his color box into the river Epte in a blind rage, then was obliged to telegraph Paris, once he calmed down, to have a new one delivered. On another occasion, he flung himself into the Seine. “Luckily no harm was done,” he reassured a friend. Monet’s canvases likewise felt his wrath. Jean-Pierre Hoschedé witnessed him committing “acts of violence” against them, slashing them with a penknife, stamping them into the ground or thrusting his foot through them. An American visitor saw a painting of one of his stepdaughters with “a tremendous crisscross rent right through the centre”—the result of an enraged Monet giving it a vicious kick. Since he had been wearing wooden clogs at the time, the damage was considerable. Sometimes he even set fire to his canvases before he could be stopped. On occasion his rages became so intense that he would roam the fields and then, to spare his family, check into a hotel nearby in Vernon. At other times he retreated to his bedroom for days at a time, refusing both meals and attempts at consolation. Friends tried to coax him from his gloom with diverting trips to Paris. “Come to Paris for two days,” Mirbeau pleaded with him during one of these spells. “We shall walk. We shall go here and there...to the Jardin des Plantes, which is an admirable thing, and to the Théâtre-Français. We shall eat well, we shall say stupid things, and we shall not see any paintings.” There was another contradiction in Monet’s practice. He loved to paint and, indeed, he lived to paint—and yet he claimed to find painting an unremitting torment. “This satanic painting tortures me,” he once wrote to a friend, the painter Berthe Morisot. To a journalist he said: “Many people think I paint easily, but it is not an easy thing to be an artist. I often suffer tortures when I paint. It is a great joy and a great suffering.” Monet’s rage and suffering before his easel reveal the disingenuousness of his famous comment about Vincent van Gogh. Mirbeau, who owned Van Gogh’s Irises, once proudly showed the work to Monet. “How did a man who loved flowers and light so much,” Monet responded, “and who painted them so well, make himself so unhappy?” Some of Monet’s friends regarded his torture and suffering as a necessary condition of his genius—as a symptom of his search for perfection, or what Geffroy called the “dream of form and color” that he pursued “almost to the point of self-annihilation.” After witnessing yet another fit of dyspepsia, Clemenceau wrote to Monet that “if you were not pushed by an eternal search for the unattainable, you would not be the author of so many masterpieces.” As Clemenceau once explained to his secretary apropos of Monet’s dreadful fits of temper: “One must suffer. One must not be satisfied...With a painter who slashes his canvases, who weeps, who explodes with rage in front of his painting, there is hope.”

Clemenceau must have realized that in persuading Monet to paint large-scale canvases of his water lily pond he had not only rekindled the painter’s hopes but also, as a sore temptation to fate, his exasperation and rage.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherBloomsbury USA

- Publication date2017

- ISBN 10 1632860139

- ISBN 13 9781632860132

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages416

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_1632860139

Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. Seller Inventory # 1632860139-2-1

Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Seller Inventory # 353-1632860139-new