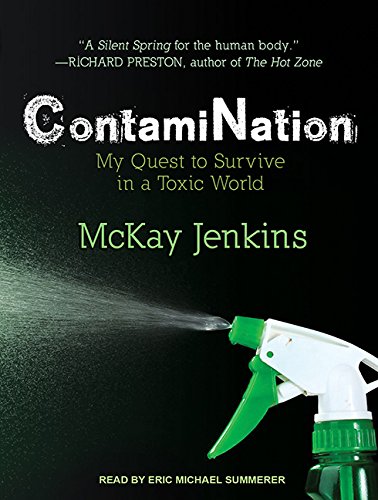

ContamiNation: My Quest to Survive in a Toxic World

From the moment he left the hospital, Jenkins resolved to discover the truth about chemicals and the "healthy" levels of exposure we encounter each day as Americans. He spent the next two years digging, exploring five frontiers of toxic exposure-the body, the home, the drinking water, the lawn, and the local box store-and asking how we allowed ourselves to get to this point. Most important, though, Jenkins wanted to know what we can do to turn things around. Though toxins may be present in products we all use every day, there are ways to lessen our exposure. ContamiNation is an eye-opening report from the front lines of consumer advocacy.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

PRAISE FOR

ContamiNation

“A Silent Spring for the human body.”

—Richard Preston, author of The Hot Zone

“Jam-packed with information and not only an invaluable resource for those interested in protecting their loved ones, but a sound investment and a book that will pay health dividends for a lifetime.”

—Robyn O’Brien, author of The Unhealthy Truth and founder of AllergyKids Foundation

“In this wonderfully readable journey of a book, McKay Jenkins illuminates not only the science of everyday toxic compounds but the best ways to manage them in everyday life. Read it and keep it. You’ll be glad you did.”

—Deborah Blum, Pulitzer Prize–winning author of The Poisoner’s Handbook

“McKay Jenkins allows the discovery of a tumor in his left hip to lead him—and us—into the world of failed chemical regulations in a story of unflinching courage combined with hardheaded research. It’s chock-full of suspense . . . and footnotes, too.”

—Sandra Steingraber, author of Living Downstream

“In this serious exposť that is surprisingly entertaining and positive, Jenkins uncovers the ubiquity and danger of [everyday] chemicals and offers some solutions, both personal and political.”

—Publishers Weekly, starred review

ALSO BY McKAY JENKINS

Bloody Falls of the Coppermine

The Last Ridge

The White Death

The Peter Matthiessen Reader (editor)

The South in Black and White

Prologue

On a crisp fall afternoon a couple of years ago, I went in for a routine two-year checkup with my internist. Everything seemed to be fine: My home life was happy and nurturing. I had never smoked. I ate right, got plenty of rest, and had been a dedicated runner and cyclist my entire adult life. Save for the usual aches and pains, nothing had ever been wrong with my body, and as long as I was smart about it, I figured, I’d still be riding my Fausto Coppi racing bike well into my eighties.

My only complaint, I told my doctor, was a faint tightness in my hip that I had felt off and on for two years—and odd, sharp twinges between my left thigh, knee, and shin that occasionally accompanied it. Sometimes the skin on my leg itched. Sometimes it burned. Sometimes the ligaments in my knee hurt. I’d consulted with a dermatologist months before, but had gotten no answers. Were these symptoms related? My internist was perplexed. Perhaps it was an “overuse injury,” he said, something I’d developed from too much running in the woods or riding the rural roads near my home. Like anyone who has tried to stay in shape through their postcollege years, I was familiar with such aches and pains. As the years went by, fewer and fewer were the days when I didn’t feel some minor muscle or joint ache after even a light workout. I was getting older, and so was the machinery.

My internist looked me over and agreed that my pains were probably related to exercise, and he suggested I see an orthopedist at a nearby sports medicine clinic. I called and got an appointment that very morning. I walked into the orthopod’s office ready for a quick diagnosis and a pat on the head. “Someone as fit as you can expect to have occasional ligament stress,” I expected him to say. “Here’s the name of a physical therapist. Go get a massage, and check in with me on your seventy-fifth birthday.”

This is not what he said.

After hearing my description of the pain, the orthopedist rotated my hip and knee a couple of times. He seemed puzzled. This didn’t seem like a joint problem, and in any case the pain in my knee was probably “referred” pain radiating from my hip. He suggested I get an MRI to help him see a bit more clearly what was going on with my soft tissue.

Okay, I thought: people get MRIs all the time. Especially athletes. They’d probably just find a slight tear in some connective tissue, I’d buy a new pair of running shoes, and away I’d go. Worst case? A little minor surgery to fix an abraided tendon. I got an appointment that afternoon, spent forty-five unpleasant minutes inside a clanging metal tube, and went home to wait for the results—which, given the routine nature of the exam, I figured would take a few days, or even weeks.

I was standing in my living room when the phone rang just a few hours later. This was an awfully quick turnaround, I thought, looking at the caller ID. These lab techs must be having a pretty light day at the office. But when I picked up the phone and heard the orthopedist’s voice, I knew even before he spoke that something was amiss.

Hello, Mr. Jenkins, he said, then paused. You have a suspicious mass in your abdomen, he said. It’s growing inside your left hip. Here is the number for an oncologist. You need to call him right away.

—

What can you say about such moments? I remember hanging up the phone. I remember looking at my wife, Katherine, and looking at my children putting together a puzzle on the floor in the next room. My son was four, my daughter not yet eighteen months. I fell apart.

Far worse than my fears for myself were my worries about my kids. How would they get by without a father? Trying to protect them from the initial shock of the news, Katherine and I took turns taking our cell phones outside to talk to doctors and loved ones. Standing in the yard, trying to set up a date for a CT scan, I would look through the living room window to see my kids playing together. I imagined the same scene, with me gone. I felt like a ghost.

Katherine and I passed the next three weeks in a kind of silent panic. We spent anxious hours on the Internet, blindly researching what this thing was that was growing between my hip and my belly. This was a very bad idea. We called every doctor we knew.

I held it together enough to keep teaching my classes at the University of Delaware, which is about an hour north of our home in Baltimore. One day, when I returned to my office after a morning class, there was a message on my phone. It was from Katherine. I found an oncologist, she said, but you need to get here fast; he’s really busy and has only one opening this week. I ran into my classroom, scrawled “Class canceled” on the blackboard, and dashed off to my car.

When I got to the hospital, Katherine was already there, waiting in the parking lot. We hugged, and went inside. I was short of breath. A nurse escorted us into an examination room, and a few minutes later, the oncologist strode in with my MRI images under his arm. He slapped them up on a backlit screen. You see this? he asked. That’s your hip. Now, see that round thing next to it? That’s not supposed to be there.

He reached over to the examination table and began scribbling diagrams on a sheet of sanitary paper. He sketched out what he thought was going on. Although he couldn’t be certain without further tests, the tumor was likely a soft-tissue sarcoma, an ugly cancer of the fibers connecting my hip to the muscles and nerve tissues of my left leg. The prognosis depended on how big the tumor was, where precisely it was growing, exactly how aggressive it was. I could get a biopsy of the tumor, which would provide a look at its cellular profile, but there was always the risk of a biopsy needle inadvertently spreading malignant cells outside the tumor itself. What to do?

At worst, this was, well, very bad. At best, a surgeon could cut out the tumor, but might be compelled to sever my femoral nerve, the trunk line that connects the nerves in the leg to the spine. Which meant I would probably never run or ride my bike again. And then I’d have to remain vigilant to see if the cancer returned. The doctor ripped off the sheet of sanitary paper, now four feet long, and handed it to me.

As he continued to speak, I felt myself leaving my body. My mouth continued to move, but the rest of me was floating, looking in from the outside. I saw myself shake hands with the doctor. I saw Katherine take my hand and lead me outside. It wasn’t until we made it back to the parking lot and I dialed my brother on my cell phone that I returned to my body. “Brian, it’s McKay,” I said. “I just came from a doctor’s office. I have cancer.” The floodgates opened.

To this day, the ride home has remained indelible. Once-generic landmarks still vibrate with the terror I felt that day: the gas station where I stopped to call my friend Wes. The curb by our home where I called my friend Tom. Rather than relieving my anxiety, each telling made the story more concrete. This was really happening. But how? This was not a grinding descent into illness; it was a bolt from the blue. I did not feel sick, and never had. My mind raced. How could I possibly have cancer?

Beyond the panic, of course, was a question. Where had this thing, this “suspicious mass,” come from? No one seemed to know. Not my primary care doctor, not my orthopedist, not even my oncologist. In medicine, cause and effect are not always clear.

After weeks of scrambling and using every connection I could muster, I found a slot on the schedule of a renowned surgeon at a New York medical center. Katherine and I drove north, dropped our kids off at their aunt and uncle’s apartment, and went to the hospital.

In the morning hours before my operation, I sat on a couch in a waiting room in a light-blue surgical gown. I wore headphones, listening to the Dalai Lama offering counsel about facing one’s own death. Life is a series of transitions, he said. Dying is one of them. It’s vitally important to remain clear-eyed during these times, to see things Just As They Are.

Okay, I thought. I will do my best. But seeing things clearly is not always so easy. Especially when it comes to understanding illness and its root causes.

—

At some point, I looked up to see the outstretched right palms of a pair of researchers, a man and a woman in their twenties, clipboards at their sides and kind, self-conscious expressions on their faces. I took off my headphones and we shook hands. We’d like to ask you a few questions before you go into surgery, they said. Sure, I said. I was feeling strangely serene and, I confess, a bit melodramatic: If I’m going to die, I thought, the least I can do is be a model for others. Go out gracefully. Make the Dalai Lama proud.

The researchers sat down on a couch across from Katherine and me, placed their clipboards on their laps, and began probing. The first questions were pretty standard: What ethnic group best describes you? Um, white. How far did you make it in school? I have a PhD, I said. How many packs of cigarettes have you smoked per day, on average? None, I said. Ever. The researchers nodded, and scribbled. How much alcohol? A couple of beers a week, I said. I managed a wan smile. Please don’t tell me I have a tumor because I drink beer.

Then the questions changed, from ones I had been asked by doctors dozens of times before to ones I had never been asked in my life.

How much exposure had I had to toxic chemicals and other contaminants? In my life? I asked. This seemed like an odd question. What kind of chemicals do you mean? The researcher began reading from a list, which turned out to be long. Some things I had heard of, many others I had not. Metal filings? Asbestos dust? Cutting oils? I didn’t think so. What’s a cutting oil? How about gasoline exhaust? Asphalt? Foam insulation? Natural gas fumes?

Where was this going?

I was not a machinist, or a car mechanic, or a building contractor. The words kept coming. Vinyl chloride? I wasn’t sure. What was that? How about plastics? Are you kidding? Everything is made of plastic. Dry-cleaning agents? I shot a glance at Katherine and managed a smile; I was not exactly known for my natty attire, and I hadn’t darkened a dry cleaner’s door in years. On and on it went. Detergents or fumes from plastic meat wrap? Benzene or other solvents? Formaldehyde? Varnishes? Adhesives? Lacquers? Glues? Acrylic or oil paints? Inks or dyes? Tanning solutions? Cotton textiles? Fiberglass? Bug killers or pesticides? Weed killers or herbicides? Heat-transfer fluids? Hydraulic lubricants? Electric fluids? Flame retardants?

By now I had begun to feel distinctly uncomfortable. Not about my history of “industrial” exposures, which were nonexistent, but about the myriad, and mostly invisible, chemicals the researchers seemed to be curious about. What was a flame retardant, exactly, and how in the world would I know if I had been exposed to one? I had never used pesticides, but Lord knows there were plenty in my neighborhood.

The questions shifted again.

We’d like to ask you about your job history, they said. What had I done before I became a professor? Well, I thought, I hadn’t exactly been working in a chlorine plant. Before teaching English, I spent a decade writing for newspapers. I’d spent a lot of college summers waiting tables in restaurants and, before that, washing dishes. Oh, wait—there was that one summer after college when I worked in a garage, pumping gas and changing people’s oil. Could that have been it? And was that the point of all these questions? To find a single cause of this tumor? If so, why would they be so interested in what I had done for work thirty years before?

Again, the researchers changed their tack. Now we’d like to ask you about the places you’ve lived, they said. If my employment history seemed fairly benign, I had spent a lot of time living in big, industrial cities. Again, going backward in time: Baltimore, Philadelphia, central New Jersey, Atlanta, Seattle, Annapolis, Manhattan, western Massachusetts, suburban New York.

Any cancer in my family history? My paternal grandfather had died of prostate cancer at an advanced age, I said. My mother had had malignant melanomas removed from her skin. I had, thus far, showed signs of neither.

Had I ever lived within a mile of any kind of waste incinerator, either at a city dump or a hospital? Not that I knew of. I had never worked in an industrial plant; wasn’t that where all these chemicals were concentrated? A decade earlier, I had built a couple of canoes, but I had done all my fiberglassing outdoors. I had painted a bedroom or two. Who hadn’t? Yet the longer the questioning went on, the more I began to realize that I didn’t have the faintest idea about how many of these chemicals I had come into contact with over the years. After all, just because I had never worked in a factory did not mean that I hadn’t been exposed to the products these factories made. But once chemicals were turned into products, they stayed put. Didn’t they?

The researchers, to be fair, were not there to talk about these larger questions. They were there to ask their questions, and when they were finished, they stood up to leave. The young guy gave me a parting look that seemed slightly melancholy, and they said good-bye.

—

A couple of hours later, a doctor led me into the operating room, and I lay down on the table. How in God’s name did I end up here, I wondered. The room was remarkably cold. Around me, a dozen faces in blue hats and masks scurried around, tending to monitors and swinging trays of instruments at my bedside. How you doin’? asked a man who introduced hims...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherTantor Audio

- Publication date2016

- ISBN 10 1515950328

- ISBN 13 9781515950325

- BindingAudio CD

- Rating

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

ContamiNation: My Quest to Survive in a Toxic World

Book Description Condition: Good. All pages and cover are intact (including the dust cover, if applicable). Spine may show signs of wear. Pages may include limited notes and highlighting. May include From the library of labels. Shrink wrap, dust covers, or boxed set case may be missing. Item may be missing bundled media. Ships same or next business day with tracking emailed direct to you!. Seller Inventory # 3U1IBA0036A2_ns