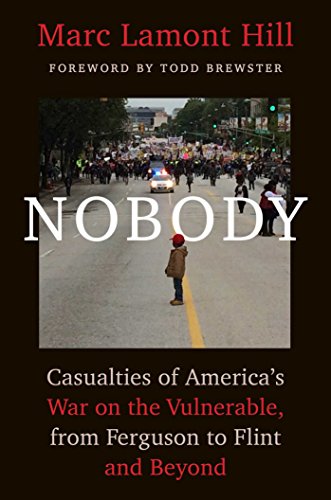

Nobody: Casualties of America's War on the Vulnerable, from Ferguson to Flint and Beyond - Hardcover

“[Nobody] examines the interlocking mechanisms that systematically disadvantage 'those marked as poor, black, brown, immigrant, queer, or trans'—those, in Hill’s words, who are Nobodies...A worthy and necessary addition to the contemporary canon of civil rights literature.” —The New York Times

“An impassioned analysis of headline-making cases...Timely, controversial, and bound to stir already heated discussion.” —Kirkus Reviews

“A thought-provoking and important analysis of oppression, recommended for those seeking clarity on current events.” —Library Journal

Unarmed citizens shot by police. Drinking water turned to poison. Mass incarcerations. We’ve heard the individual stories. Now a leading public intellectual and acclaimed journalist offers a powerful, paradigm-shifting analysis of America’s current state of emergency, finding in these events a larger and more troubling truth about race, class, and what it means to be “Nobody.”

Protests in Ferguson, Missouri and across the United States following the death of Michael Brown revealed something far deeper than a passionate display of age-old racial frustrations. They unveiled a public chasm that has been growing for years, as America has consistently and intentionally denied significant segments of its population access to full freedom and prosperity.

In Nobody, scholar and journalist Marc Lamont Hill presents a powerful and thought-provoking analysis of race and class by examining a growing crisis in America: the existence of a group of citizens who are made vulnerable, exploitable and disposable through the machinery of unregulated capitalism, public policy, and social practice. These are the people considered “Nobody” in contemporary America. Through on-the-ground reporting and careful research, Hill shows how this Nobody class has emerged over time and how forces in America have worked to preserve and exploit it in ways that are both humiliating and harmful.

To make his case, Hill carefully reconsiders the details of tragic events like the deaths of Michael Brown, Sandra Bland, and Freddie Gray, and the water crisis in Flint, Michigan. He delves deeply into a host of alarming trends including mass incarceration, overly aggressive policing, broken court systems, shrinking job markets, and the privatization of public resources, showing time and time again the ways the current system is designed to worsen the plight of the vulnerable.

Timely and eloquent, Nobody is a keen observation of the challenges and contradictions of American democracy, a must-read for anyone wanting to better understand the race and class issues that continue to leave their mark on our country today.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Todd Brewster is a longtime journalist who has worked as an editor for Time and Life and as a senior producer for ABC News. He is the coauthor with the late Peter Jennings of the bestselling books The Century, The Century for Young People, and In Search of America, and the author of Lincoln's Gamble.

Forty years from now, we will still be talking about what happened in Ferguson. It will be mentioned in high school history textbooks. Hollywood studios will make movies about it, as they now make movies about Selma. Politicians will talk about “how far we have come since Ferguson” in the same way they talk today about how far we have come since Little Rock, Greensboro, or Birmingham.

Ferguson is that important.

But why?

After all, to some, Ferguson isn’t as worthy as other markers on the historical timeline of social-justice struggle. And Ferguson’s native son Michael Brown, whose tragic death in 2014 put the small Missouri town on the map, was certainly no traditional hero. He did not lead a march or give a stirring speech. He did not challenge racial apartheid by refusing to sit in the back of a bus, attempting to eat at a “Whites only” lunch counter, or breaking the color barrier in a major professional sport. He wrote no books, starred in no movies, occupied no endowed chair at a major university, and held no political office. He was no Jackie Robinson, no Rosa Parks, no Bayard Rustin, no Fannie Lou Hamer, no Barack Obama. If he could see what has happened in reaction to his death, he would likely be stunned.

Brown was just eighteen years old on the morning of Saturday, August 9, 2014, when he decided to meet up with his friend Dorian Johnson—who would later become Witness 101 in the Department of Justice (DOJ) federal investigation report—and together they settled on a mission to get high. Johnson, who was twenty-two, had not known Brown very long but, being older, considered himself as somewhat of a role model to the teen. Although he was unemployed, Johnson worked whenever he could find available jobs, paid his rent on time, and consistently supported his girlfriend and their baby daughter.

Brown had just graduated, albeit with some difficulty, from Normandy High School, part of a 98 percent African-American school district where test scores are so low that it lost state accreditation in 2012.1 In addition to low test scores, incidents of violence have become so common at Normandy that it is now considered one of the most dangerous schools in Missouri.2 Conditions in the Normandy School District are so dire that it has become a talking point in the school-choice debate, with conservatives pointing to the schools’ failures as evidence that privatized educational options are necessary.3 Despite this troublesome academic environment, Brown, like many teenagers of color, had a positive and eclectic set of aspirations. He wanted to learn sound engineering, play college football, become a rap artist, and be a heating and cooling technician; he also wanted to “be famous.”4, 5 All of this was part of the conversation between Brown and Johnson that morning.

In need of cigarillos to empty out for rolling paper for their marijuana blunts, Brown and Johnson entered Ferguson Market and Liquor, a popular convenience store at 9101 West Florissant Avenue. As video footage shows, Brown swiped the cigarillos from the counter without paying. The store’s owner, an immigrant from India6 who did not speak English, came around to challenge him. Brown, whose nickname “Big Mike”7 derived from his six-foot-four-inch and nearly three-hundred-pound frame, gave a final shove8 to the shopkeeper before departing. While the surveillance camera captured the entire interaction, it did not show how badly the incident shocked Johnson. He had never seen Brown commit a crime, nor had Brown given him any reason to think he would. “Hey, I don’t do stuff like that,” he said to Brown as they walked home, knowing that the shopkeeper had promised to call the police. Quickly, Johnson’s feelings shifted from shock and anxiety about being caught on camera to genuine concern for Brown. He turned to him and asked, “What’s going on?”9

While interesting, all of this was mere overture to the main event that tragically awaited Brown and Johnson, one that would make both of them unlikely entries in the history books. Brown and Johnson were in the middle of residential Canfield Drive a few minutes later when twenty-eight-year-old police officer Darren Wilson saw the two jaywalking “along the double yellow line.”10 According to Johnson, Wilson told them to “get the fuck on the sidewalk,” though Wilson denies using profanity.11, 12 Regardless of the tone of their initial exchange, the interaction created room for Wilson to link Johnson and Brown to the robbery report and suspect description that had been given over the police radio. The next forty-five seconds—disputed, dissected, and debated ad nauseam throughout the ensuing months—would soon became the focus of international attention.

But how could such a random encounter, in the largely unknown St. Louis suburb of Ferguson, possibly mean so much?

Until the killing of Michael Brown, this city of twenty thousand people spread across six square miles was unknown to just about anyone outside of St. Louis. One of ninety incorporated municipalities that surround St. Louis,13 located a few minutes from the famous Gateway Arch, Ferguson was established in 1855 as Ferguson Station, a train depot named for William B. Ferguson, the farmer who deeded the land to the North Missouri Railroad. Michael McDonald—the White baritone soul singer famous for his time performing with Steely Dan and the Doobie Brothers, as well as his albums paying tribute to the “Motown sound”—is from Ferguson;14 so was the aviation pioneer Jimmy Doolittle, who received the Medal of Honor for the Doolittle Raid on Tokyo in 1942. In the late 1940s, while he was a member of the St. Louis Cardinals, baseball slugger Enos “Country” Slaughter lived in Ferguson as well. Slaughter is famous for scoring the winning run against the Boston Red Sox in Game 7 of the 1946 World Series, a “mad dash” from first to home that is still remembered fondly by old-timers in the town. He was also among the most vocal of the hundreds of racial catcallers who greeted Jackie Robinson from the opposing dugout when Robinson became the first African-American to play Major League baseball a year later. Robinson himself recalled in his autobiography that Slaughter purposely cleated him while running through first base, an incident which, ironically, unified Robinson’s Brooklyn Dodgers in defiance.15

Ferguson was, for all intents and purposes, an exclusively White city in those days, as it had been since its establishment. Its demographic profile was well guarded by both custom and law. When municipally drawn racial zoning was made illegal in 1917 with the Supreme Court’s decision in Buchanan v. Warley, the court invalidated ordinances like the one that designated certain areas of St. Louis as “Negro Blocks” and forbade Blacks from housing elsewhere.16 But privately drafted “restrictive racial covenants”—contractual obligations between two private parties requiring that a piece of real estate be sold only to White buyers in perpetuity17—still ensured that suburban neighborhoods like Ferguson and others around St. Louis remained exclusively White.18

In St. Louis—once described by civic leader Elwood Street as “northern in industrial development, but largely southern in its inter-racial attitude”19—racial covenants were used as a defense against the Great Migration that brought African-Americans north after World War I. While Blacks make up nearly 50 percent of St. Louis’s population today, only 6 percent of St. Louis’s population was Black in 1900.20 But with the growth of manufacturing opportunities in the industrial north, as well as the continuing deterioration of conditions in the old Confederacy—the decline of the cotton industry due to boll weevil infestation, the harsh realities of Jim Crow, and the arrival of a new, second-era Ku Klux Klan, with all its attendant terrorism and lynchings—thousands of southern Blacks took the journey up the Mississippi River each year, resulting in the movement of roughly six million people from 1910 to 1970. Henry Louis Gates Jr. accurately called this odyssey “the largest movement of Black bodies since slavery.”21

The transition was an uneasy one. In 1917, the same year that the Supreme Court found civil-government-instituted segregation illegal, the city of East St. Louis—just across the Mississippi River—erupted in one of the worst race riots in American history. Marauding gangs of White workers, angry that Blacks had been recruited to take their jobs and inspired by unfounded fears that Black migrants had brought smallpox and other diseases from the South, burned down whole blocks of the city’s Black neighborhoods, killing at least forty people, though likely many more.22, 23 Some police and National Guardsmen were complicit in the violence. More riots followed in the “Red Summer” of 1919, when Whites were once again the aggressors in Washington, DC, Charleston, South Carolina, and dozens of other American cities. Particularly deadly riots consumed Chicago that year, sparked by the killing of a Black sunbather who was stoned to death after crossing an invisible racial line and venturing into a “Whites only” area on Lake Michigan.24

Yet even after the violence subsided, what Blacks found in cities like St. Louis was merely a more subtle version of the structural and interpersonal racism to which they had been subjected in the South. While Black men did not have to tip their hats in deference to White men on the street or use separate public facilities, as was tradition in the South, Blacks arriving in northern cities were nonetheless greeted as a Du Boisian “problem” that needed to be contained, lest disease, vice, and even “Bolshevism” overtake the heartland. To White traditionalists, much was at stake. It was one thing for White Northerners to have fought for an end to slavery and speak glowingly about the principle of equality, so long as they could do it from afar. But when Blacks came north to live with them, to enter into their neighborhoods, their churches, their schools, their workplaces—what Black intellectual Harold Cruse called the “sacred spaces” of life—a line had been crossed that brought the Negro too close.

Real estate agents participated in the defense of their homogeneous neighborhoods. Protection from the encroaching tide of African-Americans was trumpeted in the same way as one might argue for protection from fire or burglary. To promote the 1916 segregation ordinance, for instance, one realty association produced pamphlets showing pictures of blighted areas of the city over captions declaring “An entire block ruined by Negro invasion” and pleading with people to “Save your home! Vote for segregation!”25 Even when that ordinance was declared illegal, agents followed an unwritten edict: sell homes in White neighborhoods to Black buyers and you will lose your license.

Things got more complicated in 1948, with a case involving the sale of a house roughly eight miles from Ferguson in which the Supreme Court took down restrictive racial covenants as well. The justices’ decision did not bar such private agreements per se, but said that courts could not uphold such contractual provisions, since it would involve the State acting in a discriminatory manner barred by the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. To the surprise of almost no one, the high court’s determination coincided with the sentiments that brought about “White flight,” or the movement of White families (and necessary resources) out of the cities and into the suburbs. This trend largely animated the decline of urban America in the second half of the twentieth century. Over the next twenty years, nearly 60 percent of the White population of St. Louis left the city.26

To minimize the chance that Blacks would follow Whites there, many of these suburban communities adopted strict zoning regulations. While they did not overtly exclude Blacks, these rules eliminated the kinds of environments—such as multifamily housing or industrial districts with factory jobs—that Blacks would need and desire. Ferguson, as one of these first ring suburbs, used zoning to block Black access, creating dead-end streets where roads would naturally have met the incorporated Black town of Kinloch and even barricading through streets to prevent their use for passage. But since its establishment predated the mid-century migration of Whites out of the central cities, Ferguson did not have zoning laws prohibiting apartment buildings or factories.27 As a result, places like the Canfield Green apartments, where Michael Brown and Dorian Johnson lived, and factories like the now demolished seven-thousand-square-foot Emerson Electric Company plant on West Florissant Avenue provided the types of housing and employment opportunities that drew Black people to the city.28

Named for John Wesley Emerson, the Civil War commander for the Union Army and Missouri Circuit Court judge who helped found it, Emerson Electric Company was a major defense contractor and the largest producer of airplane gun turrets for the American effort in World War II. Like many American firms, it has since become much more diversified, focusing now on the manufacture of equipment for monitoring industrial processes and components for HVAC systems.29 To do so, Emerson has taken advantage of the labor markets of the low-wage, low-regulation Far East, where most of its manufacturing is now done. The Ferguson factory first outsourced labor overseas in the late 1970s and began shutting down operations in the 1980s.30 All that remains locally is the Emerson corporate headquarters, situated within minutes of where Michael Brown was killed. There, as much of the town lives in suburbanized poverty, Emerson’s CEO, David Farr, guides the company while pulling in annual compensation worth as much as twenty-five million dollars.31

. . . .

THERE WAS, AND IS, no disagreement as to the result of Darren Wilson’s confrontation with Michael Brown. After a brief struggle at Wilson’s car,32 Brown fled the scene and was pursued by the officer in a chase that ended with the unarmed Brown struck dead by bullets fired from Wilson’s Sig Sauer S&W .40-caliber semiautomatic pistol. What remains, however, is the dispute about whether the shooting was criminal. Both the St. Louis County grand jury, which met for twenty-five days over a three-month period and heard a total of sixty witnesses,33 as well as a separate investigation done by the USDOJ that investigated potential civil-rights violations, determined that there was no cause to indict Wilson for his actions. The seven men and five women who made up that grand jury—three Black and nine White, chosen to reflect the racial makeup of St. Louis county, though not the overwhelmingly Black population of Ferguson itself—and the FBI investigators working on the federal study concluded that Brown had not been shot in the back, as some had initially said. Assertions that Brown had put his hands in the air and said “Don’t shoot” in the moments before he was killed—an image so disturbing, it became a rallying cry for protesters determined to see that Wilson was indicted—were also not supported by witnesses who watched the encounter. Those conclusions, when matched with Wilson’s testimony that he feared for his life in the confrontation with Brown and with Missouri’s broad latitude for police use of deadly force,34 left little legal room to justify an indictment. But the law does not tell the full story.

The law is but a mere social construction, an artifact of our social, economic, political, and cultural conditions. The law represents only one kind of truth, often an unsatisfying truth, and ultim...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherAtria Books

- Publication date2016

- ISBN 10 1501124943

- ISBN 13 9781501124945

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages272

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 3.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Nobody: Casualties of America's War on the Vulnerable, from Ferguson to Flint and Beyond

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new1501124943

Nobody: Casualties of America's War on the Vulnerable, from Ferguson to Flint and Beyond

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # newMercantile_1501124943

Nobody: Casualties of America's War on the Vulnerable, from Ferguson to Flint and Beyond

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_1501124943

Nobody: Casualties of America's War on the Vulnerable, from Ferguson to Flint and Beyond

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon1501124943

Nobody: Casualties of America's War on the Vulnerable, from Ferguson to Flint and Beyond

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think1501124943

Nobody: Casualties of America's War on the Vulnerable, from Ferguson to Flint and Beyond

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. 1. Seller Inventory # 1501124943-2-1

Nobody: Casualties of America s War on the Vulnerable, from Ferguson to Baltimore and Beyond

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: Brand New. 320 pages. 9.00x6.00x1.25 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # 1501124943

Nobody: Casualties of America's War on the Vulnerable, from Ferguson to Flint and Beyond

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard1501124943

Nobody: Casualties of America's War on the Vulnerable, from Ferguson to Flint and Beyond

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover1501124943