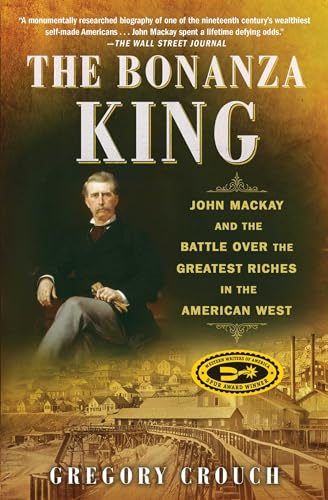

The Bonanza King: John Mackay and the Battle over the Greatest Riches in the American West - Softcover

Born in 1831, John W. Mackay was a penniless Irish immigrant who came of age in New York City, went to California during the Gold Rush, and mined without much luck for eight years. When he heard of riches found on the other side of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in 1859, Mackay abandoned his claim and walked a hundred miles to the Comstock Lode in Nevada.

Over the course of the next dozen years, Mackay worked his way up from nothing, thwarting the pernicious “Bank Ring” monopoly to seize control of the most concentrated cache of precious metals ever found on earth, the legendary “Big Bonanza,” a stupendously rich body of gold and silver ore discovered 1,500 feet beneath the streets of Virginia City, the ultimate Old West boomtown. But for the ore to be worth anything it had to be found, claimed, and successfully extracted, each step requiring enormous risk and the creation of an entirely new industry.

Now Gregory Crouch tells Mackay’s amazing story—how he extracted the ore from deep underground and used his vast mining fortune to crush the transatlantic telegraph monopoly of the notorious Jay Gould. “No one does a better job than Crouch when he explores the subject of mining, and no one does a better job than he when he describes the hardscrabble lives of miners” (San Francisco Chronicle). Featuring great period photographs and maps, The Bonanza King is a dazzling tour de force, a riveting history of Virginia City, Nevada, the Comstock Lode, and America itself.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Tens of thousands of destitute Irish immigrants lived packed into the rickety tenements of Five Points in lower Manhattan. It was the most notorious slum in the world.

The poorest and most wretched population that can be found in the world—the scattered debris of the Irish nation.

—Archbishop John Hughes, 1849

Few great men ever started further down the ladder of success than John William Mackay. He was born into dire poverty near Dublin, Ireland, on November 28, 1831. Mackay, his younger sister, and his mother and father shared a crude cottage with the family pig. That was in no way unique, for grinding need wore at the foundations of nineteenth-century Ireland. Walls of loose-stacked stone slathered in mud enclosed the one-room shelters that housed fully half the Irish population. Most didn’t have windows. A roof of tree branches, sod, and leaky thatch protected them from the worst of the Atlantic rains; an open peat fire warmed them through the dark winter months. Beds and blankets were rare luxuries. Most Irish families slept on bare dirt floors alongside their domestic animals. A British government official reporting on the living conditions of the Irish peasantry noted that “in many districts their only food is the potato, their only beverage water. . . . Pigs and manure constitute their only property.” Like many Irish families, the Mackays didn’t always get enough to eat.

They were Catholic, and in the eyes of Ireland’s Gaelic Catholic majority, theirs was a conquered country, subjugated to the foreign English crown since the mid-seventeenth century. Although Catholics constituted more than three-quarters of Ireland’s population, by 1800, 95 percent of the country’s land had passed into the hands of English or Anglo-Irish Protestant aristocrats. Interested only in extracting rents and raising grain and cattle for cash sale in England, those absentee owners typically spent the bounty of the Irish countryside supporting lavish lifestyles in England while the laborers and tenants who worked their estates endured desperate poverty.

Irish tenants exchanged their labor for the lease on the small plots of dirt they needed to feed themselves. On such meager acreages, only the potato yielded sufficiently to feed a family. Poor Irish men and women ate them at almost every meal. Chronically indigent, often underfed, unable to purchase land, deprived of political power, and ferociously discriminated against for the sin of being Catholic, more than a million people left Ireland in the first four decades of the nineteenth century.

The Mackays held firm until 1840, but when young John reached the age of nine, the family immigrated to America. In 1800, some 35,000 Irish men and women lived in the United States. When the Mackay family arrived forty years later, that number had bloated to 663,000, the overwhelming majority of them poor and barely educated. Unskilled laborers nailed to the cross of extreme poverty, most Irish male immigrants did casual day labor, taking whatever employment they could find. Ten to twelve hours a day, six days a week, they performed the brutal, backbreaking toil nobody else would do, for paltry wages, digging sewers and canals, excavating foundations, loading ships and wagons, carrying hods of bricks and mortar for skilled masons, paving streets, and building railroad beds. Irish women worked as washerwomen and domestic servants, or sewed piecework in the needle trades. Widows took in boarders and collected rags they recycled into “shoddy,” a cheap cloth made from shredded scraps of wool. In New York City, Irish peddlers lugged merchandise to every neighborhood, hawking sweet corn, oranges, root beer, bread, charcoal, clams, oysters, buttons, thread, fiddle strings, cigars, suspenders, and a host of other inexpensive items. Rag-clad Irish children scavenged wood, coal, scrap metal, and glass, swept street crossings for tips, shined shoes, dealt apples and individual matches, and sold newspapers.

Rather than be grateful for their inexpensive labor and service, established Yankee Protestants despised the Irish immigrants, scorning them as “superstitious papists” and “illiterate ditch diggers.” The huge numbers of Irish-born Catholics enfranchised by the universal white male suffrage of Jacksonian democracy terrified native-born Americans. Many Protestants judged Catholicism—with its devotion to an imagined papal dictatorship—to be philosophically incompatible with the ideals of American democracy. Established, respectable Americans discriminated ferociously against the filthy Irish suddenly infesting the slums of eastern cities and manning the work camps of railroad- and canal-building concerns. Help wanted advertisements often carried the qualifier “any color will answer except Irish.” The twin millstones of being Irish and Catholic kept most Irish immigrants firmly anchored to the bottom of the American social spectrum.

In 1840, the year the Mackay family crossed the Atlantic, nearly half of the eighty-four thousand immigrants received in the United States came from tiny Ireland, and like thousands of their countrymen, the Mackays settled in New York City. The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 had transformed the city into the most important port in the Western Hemisphere. Dense forests of masts and spars sprouted from ships docked against the piers, wharfs, quays, and slips cramming the southern shores of Manhattan Island. Banking, insurance, and manufacturing industries developed alongside the trade. New York’s population grew from 123,700 in 1820, five years before the canal opening, to 202,000 in 1830 and roughly 313,000 in 1840, making New York three times the size of Baltimore, America’s second largest urban concentration.

The Mackay family took quarters on Frankfort Street in the heart of the Fourth Ward. In their earliest days, the city’s Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth wards running from the East River to the Hudson River between City Hall Park and Canal Street had housed a mixed community of free blacks and French, German, Polish, and Spanish immigrants, but as more and more people abandoned Ireland for the United States, those neighborhoods acquired a distinctly Irish flavor, an influence that spread north into the Fourteenth Ward and east to permeate the Seventh. When the Mackays arrived in 1840, the Irish presence filled much of lower Manhattan,I and it centered on the Five Points intersection, just a few hundred yards from the Mackay family’s front door. At that time, Five Points was the most notorious slum in the United States.

Originally, Five Points had been an attractive marshy pond, the Collect. As the city expanded, tanneries and slaughterhouses set up on its banks and dumped their effluents into the pond. The Collect grew so disgusting that it depressed local real estate values. The municipality dug a canal to drain it (and gave a name to Canal Street), and when that didn’t improve conditions, filled in the pond. Without bedrock beneath it, the landfill proved too unstable to support major construction. Speculators bought the land and erected cheap one- to two-and-a-half-story wooden houses among the businesses of the neighborhood.

Property owners originally designed the houses for artisans, their families, and their workshops, but as budding manufacturing industries undercut the prosperity of individual craftsmen, landlords discovered that they made much larger profits by partitioning the buildings into tiny rooms rented to immigrants. Originally known as “tenant houses,” the term morphed into the word “tenements.” The rickety wooden fabrications were damp and frigid in winter, sticky and sweltering in summer, and always choked with foul, smoky air from the fires of cooking and warming. Inside, entire families crammed into single rooms entered from dim, lightless corridors. Unceasing din harried the inhabitants. Street noise reverberated in the front rooms. Rooms in the rear filled with the sounds of neighbors facing the backyards and alleys—spouses argued, babies screamed, siblings fought. Occupants shared filthy, overflowing outhouses with dozens of neighbors and drew water from common hydrants outside. The horses, mules, and oxen used everywhere for drayage defecated in the streets. The municipal government sponsored no garbage collection. Foot, animal, and wheeled traffic churned the improperly drained streets and alleys into fetid quagmires choked with animal corpses, human and animal waste, kitchen slops, and ashes. The stench was overwhelming.

Mice, rats, roaches, fleas, lice, maggots, and flies thrived in the squalor. Thousands of feral pigs roamed the streets. Despite the pigs’ grotesque snouts, coarse hair, and black-splotched skin, New York residents tolerated them because the pigs were far and away the city’s most effective street cleaners, even as they waged pitched battles with wild dogs for choice morsels of food. Among their own kind, the pigs rutted with loud, gleeful abandon. Refined Knickerbocker ladies sent up howls of protest, complaining that exposure to such indiscriminate sexual behavior undermined their respectability and lowered the moral tone of the whole city. For Irish women, most of whom had been raised in a rural countryside, fornicating domestic animals barely seemed worth a raised eyebrow. Besides, the pigs supplied valuable meat.

The outrageous quantities of animal and human feculence contaminated local wells. Dysentery, typhoid fever, diarrhea, and other waterborne diseases wreaked far more havoc in the immigrant wards than they did in the rest of the city, as did tuberculosis, diphtheria, smallpox, measles, mental disorders, and alcoholism. Crime and prostitution were ubiquitous, murder commonplace. Astronomical mortality rates haunted New York’s immigrant neighborhoods.

America’s new penny newspapers thrilled readers with lurid descriptions of the violence, dirt, mayhem, poverty, and moral depravity of Five Points. Visiting journalists could seldom resist characterizing the Irish neighborhoods as nests of vipers and sinks of filth and iniquity, unable or unwilling to do justice to the poor, working-class families who lived there. Most scribes, making brief forays into the slums, had eyes only for the dark side of the Irish wards. They failed to credit the immigrants’ ferocious struggle, or to perceive the community strength building in their churches, saloons, benevolent societies, fraternal orders, and fire companies. Immigrant families bent on improving their lot in the new country fought a constant battle to maintain any semblance of dignity in the face of such filth, squalor, and anarchic ruckus. The vast majority of Irish immigrants worked as hard as humanly possible to better their lives and the lives of their children as they fought to claw their way up from circumstances so desperate they were difficult for established Yankees to comprehend.

Among the thousands of immigrant families in New York City, the Mackays struggled forward in anonymity, and for their first two years in the United States, the family did reasonably well. Mr. and Mrs. Mackay scraped together enough money to send their ten-year-old son to school. In that, John Mackay was lucky. Only about half the school-age Irish children then living in New York City received any education at all.

Disaster struck the family in 1842. John Mackay’s father died of a cause lost to history. The catastrophe forced eleven-year-old John Mackay to quit school and work to support his mother and sister. Mackay could read, write, and figure, but he would never receive another day of classroom schooling. A taciturn lad who spoke slowly and awkwardly, fighting a stutter, he’d regret his lack of formal education for the rest of his life.

In an age devoid of social safety nets, when circumstances forced Irish boys not yet old enough to apprentice to earn money to help their family survive, most of them started selling newspapers or shining shoes. No resident of Frankfort Street would have been surprised that John Mackay fell into the world of the New York newsboys after his father’s death—most of the city’s newspapers had their headquarters on Park Row a few blocks west of the Mackay family lodgings.

For a job so near the bottom of the capitalist ladder, selling newspapers forced the young boys to accept a whopping ton of risk. Most New York dailies sold for two cents, and newsboys made a half-cent profit on every sale. However, wholesalers forced the newsboys to purchase their supply outright, for 1.5 cents per paper, and the newsboys couldn’t return unsold stock. Any newspapers they didn’t sell therefore cut a significant chunk from their earnings. The newsboys called it “getting stuck,” and they hated it. The more fortunate ones, like John Mackay, knew how to read, since basic literacy conveyed a major selling advantage. A literate newsboy could scan the leading stories and make a snap judgment about how many papers he’d sell. Ones who couldn’t read had to find a trusted ally to perform the service.

Newsboys bought their stock of morning papers before sunrise and immediately hit the streets crying the headlines, their clear, young voices among the all-pervasive sounds of the New York streets. Astute newsboys tailored their cries to their intended marks, touting commercial news at the approach of a Wall Street sharp or social happenings to a fashionable lady, and they all led a rough-and-tumble territorial existence. Newsboys staked claims to the best street corners and selling locales and fiercely defended their fiefdoms against interlopers. Fistfights were common, and John Mackay both received and administered his fair share of thrashings.

Midmorning, newsboys who had exhausted their stock grabbed a bite to eat and then hustled odd jobs—perhaps sweeping street crossings or carrying packages for tips at a ferry terminal—until the late papers dropped in the afternoon. They’d repeat their selling routine into the evening. An average newsboy, on an average day, earned twenty-five to fifty cents. A good salesman, on a good day, hustling hard until he’d sold his last paper, took home between sixty cents and a dollar. A day with incendiary headlines might earn a newsboy as much as two dollars.

Selling newspapers was an endless grind, but the newsboys reveled in their self-sufficient autonomy and liberty. Each boy worked on his own account, suffering no boss. Off-duty, they crowded the rowdy galleries of the Bowery and Chatham theaters, notorious aficionados of low entertainments and equally ardent spectators at prizefights and cockfights. A love of musical and dramatic productions and sporting entertainments, engrained as welcome relief from his sharp-elbowed New York upbringing, would persist for the rest of John Mackay’s life. The man he thought the greatest in the world was innovative newsman James Gordon Bennett, founder and owner of the New York Herald, a Scottish immigrant whom Mackay often watched hustle through City Hall Square with a bundle of newspapers tucked under his arm. Unnoticed, Mackay peddled Bennett’s newspaper on New York’s dirty streets.

John Mackay sold newspapers and scrounged odd jobs for four or...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherScribner

- Publication date2019

- ISBN 10 1501108204

- ISBN 13 9781501108204

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages480

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Bonanza King: John Mackay and the Battle over the Greatest Riches in the American West by Crouch, Gregory [Paperback ]

Book Description Soft Cover. Condition: new. Seller Inventory # 9781501108204

The Bonanza King: John MacKay and the Battle Over the Greatest Riches in the American West (Paperback or Softback)

Book Description Paperback or Softback. Condition: New. The Bonanza King: John MacKay and the Battle Over the Greatest Riches in the American West. Book. Seller Inventory # BBS-9781501108204

The Bonanza King: John Mackay and the Battle over the Greatest Riches in the American West

Book Description Condition: New. Brand New! Not Overstocks or Low Quality Book Club Editions! Direct From the Publisher! We're not a giant, faceless warehouse organization! We're a small town bookstore that loves books and loves it's customers! Buy from Lakeside Books!. Seller Inventory # OTF-S-9781501108204

The Bonanza King Format: Paperback

Book Description Condition: New. Brand New. Seller Inventory # 1501108204

Bonanza King : John Mackay and the Battle Over the Greatest Riches in the American West

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 35155586-n

The Bonanza King: John Mackay and the Battle over the Greatest Riches in the American West

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Brand New!. Seller Inventory # 1501108204

The Bonanza King: John Mackay and the Battle over the Greatest Riches in the American West

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # I-9781501108204

The Bonanza King: John Mackay and the Battle over the Greatest Riches in the American West

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. Seller Inventory # 1501108204-2-1

The Bonanza King: John Mackay and the Battle over the Greatest Riches in the American West

Book Description Condition: New. . Seller Inventory # 52GZZZ00D99J_ns

The Bonanza King

Book Description PAP. Condition: New. New Book. Shipped from UK. Established seller since 2000. Seller Inventory # IB-9781501108204