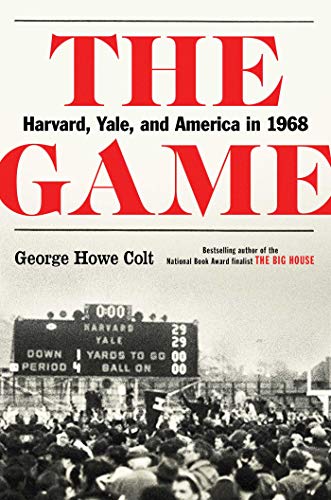

The Game: Harvard, Yale, and America in 1968 - Hardcover

From the bestselling author of The Big House comes “a well-blended narrative packed with top-notch reporting and relevance for our own time” (The Boston Globe) about the young athletes who battled in the legendary Harvard-Yale football game of 1968 amidst the sweeping currents of one of the most transformative years in American history.

On November 23, 1968, there was a turbulent and memorable football game: the season-ending clash between Harvard and Yale. The final score was 29-29. To some of the players, it was a triumph; to others a tragedy. And to many, the reasons had as much to do with one side’s miraculous comeback in the game’s final forty-two seconds as it did with the months that preceded it, months that witnessed the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy, police brutality at the Democratic National Convention, inner-city riots, campus takeovers, and, looming over everything, the war in Vietnam.

George Howe Colt’s The Game is the story of that iconic American year, as seen through the young men who lived it and were changed by it. One player had recently returned from Vietnam. Two were members of the radical antiwar group SDS. There was one NFL prospect who quit to devote his time to black altruism; another who went on to be Pro-Bowler Calvin Hill. There was a guard named Tommy Lee Jones, and fullback who dated a young Meryl Streep. They played side by side and together forged a moment of startling grace in the midst of the storm.

“Vibrant, energetic, and beautifully structured” (NPR), this magnificent and intimate work of history is the story of ordinary people in an extraordinary time, and of a country facing issues that we continue to wrestle with to this day. “The Game is the rare sports book that lives up to the claim of so many entrants in this genre: It is the portrait of an era” (The Wall Street Journal).

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

When Pat Conway decided to play football again, the one thing he didn’t want to do was embarrass himself on the field. Now he’d embarrassed himself before he’d even gotten to the field. It was the first day of practice. In the locker room, listening to the other players joking and laughing as they put on their uniforms, he had pulled on his football pants and drawn the laces tight. But something didn’t feel quite right. He snuck a glance at the players nearby and realized what it was. He had forgotten to put on his girdle, the thick cloth wrap that contained pads for his backbone and hips. The girdle went on before the pants. He looked around sheepishly, worried that someone had noticed, but everyone was busy lacing up shoulder pads or putting on cleats. Conway took off his football pants, cinched the girdle around his waist, and pulled the pants back on. He reached for a crimson stirrup sock and tugged it up his leg—until he realized that the socks, too, went on before the pants. He felt like a fool. He’d forgotten how to put on a football uniform. He unlaced his pants one more time.

Of the 117 candidates for the 1968 Harvard football team who returned to Cambridge on September 1 for three weeks of preseason practice, Pat Conway was, perhaps, the most unlikely. He was twenty-four years old, six years older than some of his teammates. He hadn’t played football in more than three years. He knew almost no one on the team. He’d be trying out for safety, a position he had never played. Six months ago, he had been dodging mortar fire in Vietnam.

Conway had played football for Harvard before. A Sporting News high school All-American from Haverhill, Massachusetts, he had arrived in the fall of 1963 and quickly established himself as a star halfback on the freshman team. (On November 22, after his 48-yard touchdown run gave Harvard a 7–6 lead over Yale, he had been standing on the goal line, ready to receive the second-half kickoff, when the referee walked over and told him that President Kennedy had been shot. Although shaken, the hyper-competitive Conway pleaded with the official not to tell anyone else so they could finish the game.) Sophomore year, Conway started at fullback for the varsity, but he was floundering academically and Harvard put him on probation. The following autumn, falling still further behind, he left school, enlisted in the Marines, and was sent to Vietnam. While his Harvard teammates were playing Yale in November 1967, he had been digging foxholes at Khe Sanh Combat Base. His tour almost up, he had reapplied to Harvard for the spring semester. By the time his paperwork came through, more than 30,000 North Vietnamese troops had surrounded the base. It would be months before Conway was able to fly home.

Conway hadn’t expected to play football when he returned to Harvard for his senior year. But that summer he’d gotten a letter from Coach John Yovicsin saying he had a year of eligibility left; did he want to rejoin the team? Yovicsin told Conway they already had someone—the captain, Vic Gatto—at right halfback, his favorite position. But they needed a safety. Conway said he’d give it a try.

The last time he had touched a football was at Khe Sanh, before all hell broke loose. Someone had come across a battered old ball, and Conway and a few other marines had tossed it around for half an hour one afternoon. Conway never saw the ball again; he assumed it had blown up in a mortar attack.

He had no real expectation of making the team. But ever since he’d started playing Pop Warner in the seventh grade, fall had meant football. Returning to college after almost three years away wouldn’t be easy. Playing football might help him get back to his old life.

Besides, Conway was lonely. He had spent July and August in Cambridge, going to summer school and living alone in a dorm in Harvard Yard, where he had spent his freshman year five years before. He was almost as old as some of his teachers. Everyone he’d been with at Harvard the first time around was off at graduate school or out in the real world. Playing football, he would meet some people. And not just any people, his kind of people: blue-collar guys, regular guys, guys who knew how to work hard. If he didn’t make the team, at least maybe he’d make a few friends.

That summer, Conway took long runs on the Charles River footpath. He “did stadiums”—bounding up and down the steep Harvard Stadium steps. Once in a while he was able to persuade an old high school teammate to throw a football with him. Most of the time, he was on his own. By the start of preseason, he was in pretty good shape, but football shape was something different, and he had no idea what to expect once the hitting began.

* * *

For most of the 116 other players who showed up that first day, there was a comfortable, back-to-school feel. They joshed and kidded, giving each other grief about a particularly colorful T-shirt or the length of someone’s sideburns. At the same time, they were surreptitiously sizing one another up: whose biceps looked especially prominent, which of the incoming sophomores looked as if they might be players. Over dinner they talked about their summers.

It had been a strange, unsettling few months. The summer had seemed to begin on June 6, when Robert Kennedy was assassinated, only nine weeks after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. Quarterback George Lalich and linebacker John Emery had been up late watching a movie in a Connecticut motel room, preparing to play for Harvard in the NCAA baseball tournament, when the show was interrupted with news of the shooting. They spent the rest of the night watching the coverage and wondering what the country was coming to.

The summer had ended, a week before preseason began, with the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. Offensive tackle Joe McGrath had been there, working as a congressional aide and staying in a hotel across from Grant Park, where the antiwar demonstrators gathered. One night McGrath had been in the hotel basement, mimeographing the latest draft of the party platform, when a few dozen Chicago policemen, bloodied and furious after an encounter with rock-throwing protestors, came in to regroup. Another night, he’d walked out of the hotel and seen a mass of policemen lined up across from thousands of demonstrators, who were shouting “Oink oink” and “Fascist pigs.” Every so often, billy clubs flailing, the police charged into the crowd, which scattered into the park before coming forward to renew its taunts—at which point the police charged again. For several nights, as delegates at the convention argued over whether to adopt an antiwar plank into the party platform, downtown Chicago itself resembled something of a war zone, as thousands of police and National Guardsmen, employing what one senator called “Gestapo tactics,” teargassed and clubbed protestors, bystanders, and journalists alike.

Between those disturbing events, the Harvard players had settled into their summer jobs. Many of them had worked in construction, which not only paid well but helped them stay in shape. Lalich had been a rod buster at a Chicago steel mill. Cornerback Mike Ananis had unloaded two-by-fours at Boston lumberyards. Not every player did heavy lifting: tackle Bob Dowd had been a counselor at a boys’ camp in New Hampshire; guard Tommy Lee Jones had acted in a summer repertory theater at Harvard, playing the title role in a blues adaptation of the fifteenth-century morality play Everyman; halfback Ray Hornblower had run with the bulls at Pamplona before bumming around Spain. Defensive tackle Rick Berne had driven across the country with a friend. It had been a mind-expanding trip: from the Deep South, where their shaggy hair and New York license plates had earned them hard stares that Berne would recall the following summer when he saw a movie called Easy Rider, to San Francisco, where they’d wandered among the flower children in Haight-Ashbury before ending up in Golden Gate Park in a vast swirl of barefoot, half-naked hippies smoking pot in broad daylight.

* * *

The first few days of preseason were always a time of unbridled optimism. The grass on the fields had just been cut, the lines were newly chalked, the uniforms were freshly washed. Everything seemed possible. Before practice even began, there was Picture Day, in which the players, dressed in their crimson game uniforms, posed for Boston photographers on the emerald greensward of Harvard Stadium, where they were encouraged to assume a variety of “action” poses rarely, if ever, seen in games: helmetless halfbacks in stiff-arming, Heisman-esque positions; quarterbacks, arms cocked, leaping like ballet dancers in mid-jeté; linebackers pouncing like cartoon cats on footballs that lay, conspicuously unattended, on the grass.

The players’ spirits were high, their coach’s somewhat less so. John Yovicsin was cautious by nature, and he had even more reason to be this year, his twelfth at Harvard. Despite having ended the previous season with a near-upset of heavily favored Yale, Harvard had tied for fourth place in the eight-team Ivy League. Of twenty-two starters, fourteen had graduated, including five who had been named All-Ivy. There were only fourteen returning lettermen, the fewest in the league. By the time preseason started, due to injuries over the summer, they were down to eleven. The biggest blow was the loss of senior defensive back John Tyson, whom the press book described as “Harvard’s top candidate for All-East and All-American honors.” Yovicsin told reporters that Tyson couldn’t play because the knee he’d injured last season hadn’t healed, but most of the players knew the real reason: Tyson had quit the team to devote himself to black activism. It was Tyson’s shoes that Yovicsin hoped Pat Conway could fill.

Harvard did have one bona fide star: its captain, Vic Gatto, the squat, muscular halfback who entered the season as the fourth-leading rusher in Harvard history. Gatto was joined by junior Ray Hornblower, a whippet-fast halfback who had come out of nowhere the previous year to finish fifth in the league in rushing, to give Harvard what might be the top running tandem in the league. Whether the offensive line—it had only one returning letterman, the aspiring actor Tommy Lee Jones—would be able to open holes for their talented running backs was another matter. “At offensive tackle the picture is desperate,” the Crimson observed. On defense, there were a few veteran linebackers and several promising sophomores, but, as Yovicsin told the press, “I’ve never gone into a season with as many question marks.” In almost every preseason poll, Harvard was picked to finish in the bottom half of the Ivy League. “Harvard Outlook Not Too Bright” was the gleeful headline in the Yale Daily News. Even Harvard’s director of sports information, whose job required him to be optimistic, conceded that the football team, after overachieving for two seasons, might have its first losing campaign in ten years. “The well,” he said, “has finally run dry.”

* * *

Two-a-days, as the twice-daily preseason practice sessions were known, were all about finding out who wanted to hit. This year, the players had a temporary reprieve before the hitting began. Alarmed by the number of cases of heat exhaustion in the early days of practice—including twenty-four deaths among high school and college players in the previous eight years—the NCAA had decreed that the first three days of the 1968 preseason be conducted without pads. Coaches grumbled. You couldn’t tell who the real football players were until you saw them hit. But for a brief honeymoon period, practice had a summer-camp feel, as the players, in T-shirts, shorts, and helmets, improved their conditioning, rehearsed their footwork, and learned plays. On the morning of the fourth day, the walk to the fields was quieter than usual.

It wasn’t that the players hated hitting—you didn’t play football unless you liked to hit. It was that there was so much of it. Even the quarterbacks, running backs, and ends—the so-called skill positions—did a lot of hitting, when they weren’t throwing and catching and handing off. The linemen who, by implication, toiled at unskilled positions, did nothing but hit, spending four hours a day smashing into each other. There were a variety of ways to accomplish the smashing. There was the Hamburger Drill, in which a defensive lineman squared off against an offensive lineman and a running back. There was Bull in the Ring, in which the players formed a circle with one man in the center, and, as a coach called out their names, the players on the perimeter, in quick succession, tried to knock him down. There was the Board Drill, in which two linemen, straddling a two-by-four on the ground, rammed into each other like sumo wrestlers, each trying to toss the other aside. When the linemen weren’t smashing into each other, they were smashing into inanimate objects like the seven-man sled, which they shoved back and forth across the field, with a coach going along for the ride on the steel frame, goading them like a galley master. When practice was almost over and the hitting finally, mercifully, stopped, there were wind sprints—fifty yards at top speed, over and over, until the players were so exhausted they could hardly stand up.

All this took place in the heat and humidity of the city at the end of summer, when even the faintest breeze off the Charles felt like a blessing. In high school, most of the players had coaches who made it clear that only sissies drank water during practice. Mindful of the NCAA’s concerns about dehydration, the Harvard coaches weren’t quite so draconian, but they were loath to spare even a minute for a water break. The players lived for the rare occasions when the managers appeared on the field, scurrying from group to group with metal trays stocked with water-filled Dixie cups, half of whose contents had sloshed out along the way. Some of the players had heard about a new Day-Glo lemon-lime “sports drink” called Gatorade, developed by scientists at the University of Florida, and they pleaded with the trainers to get them some, but were told to make do with water. If they were feeling faint, they could gobble down some salt pills. When his teammates complained about the 90-degree heat, Tommy Lee Jones, who, before taking up acting had spent his summers working on oil rigs, would growl, “You pussies, it’s a hundred degrees in Texas.”

Unlike other Division I colleges, Ivy League schools prohibited spring practice, so there had been no organized football since the final snap of the Yale game nine months earlier. Although the coaches issued a manual of suggested exercises, there was no required off-season conditioning program. The players were expected to arrive at camp in shape; how they accomplished this was up to them. For those, like Gatto, who, the moment his Park League summer baseball season was over, launched into a systematic regimen of push-ups, pull-ups, sprints, and distance runs (Gatto was never really out of shape), preseason was exhausting enough. For those who had put off exercising till the waning days of August and then jogged around the block a few times, it was agony. Even if you came to camp in shape, hitting shape was something else. For the first three or four days of full-pad workouts, your body was so sore it took several minutes to get out of bed in the morning. Just when you...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherScribner

- Publication date2018

- ISBN 10 1501104780

- ISBN 13 9781501104787

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages400

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.99

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Game: Harvard, Yale, and America in 1968

Book Description hardcover. Condition: New. Hardcover and dust jacket. Good binding and cover. Clean, unmarked pages. Seller Inventory # 2405020074

The Game: Harvard, Yale, and America in 1968

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 4JSXJ6000IC4

The Game: Harvard, Yale, and America in 1968

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_1501104780

The Game: Harvard, Yale, and America in 1968

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover1501104780

The Game: Harvard, Yale, and America in 1968

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new1501104780

The Game: Harvard, Yale, and America in 1968

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think1501104780

The Game: Harvard, Yale, and America in 1968

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard1501104780

The Game: Harvard, Yale, and America in 1968

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon1501104780