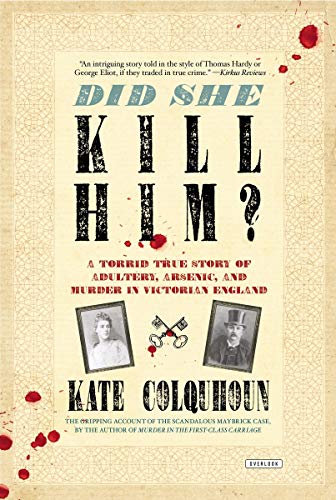

Did She Kill Him?: A Victorian Tale of Deception, Adultery, and Arsenic - Softcover

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Also by Kate Colquhoun

available from The Overlook Press

Murder in the First-Class Carriage

Copyright

For

D, F & B

... it is too painful to think that she is a woman, with a woman’s destiny before her – a woman spinning in young ignorance a light web of folly and vain hopes which may one day close round her and press upon her, a rancorous poisoned garment, changing all at once ... into a life of deep human anguish.

George Eliot, Adam Bede (1859)

I want a happiness without a hole in it ... The golden bowl ... the bowl without the crack.

Henry James, The Golden Bowl (1904)

Author’s Note

The detail of this story and all italicised speech is taken from primary record, including Home Office documents, contemporary newspaper accounts, American archives, court transcripts and Florence Maybrick’s emotionally charged memoir.

I have chosen to quote sparingly from a number of letters written by Florence and printed in earlier books about the case despite the fact that the originals have since been lost; there is no reason to believe they were not accurately quoted and they give us rare glimpses into her state of mind. Endnotes indicate where this is the case.

Although I have stuck rigorously to contemporary sources, the reconstruction of history inevitably remains to some extent a work of imagination.

ST GEORGE’S HALL, LIVERPOOL

Wednesday 7 August 1889

She had not expected them to be so quick and when the call came her pulse was still fast, her mouth dry.

She heard the key turn in the lock. Felt, rather than saw, the door swing open. Gathering her black skirts in one gloved hand and rising uncertainly from the wooden bench, she stepped out into the corridor, turning towards the stone staircase, ignoring the wardress’s offer of support.

She can hear, now, the murmur of many voices from above, the shuffling of feet, throats being cleared. The very air seems to shiver with significance. Taking each step slowly, she fights to compose her features and to calm her breathing.

Five feet, three inches tall, alabaster pale beneath a fine black veil, the slender young widow has never seemed more fragile as she emerges into the open body of a packed courtroom. Turning through a hip-height gate to her right she enters the dock, taking her seat once again towards the railings at its front. Her small hands rest deliberately in her lap. Two female prison guards are close behind, one on either side.

She woke at dawn and it is now almost ten to four in the afternoon. The stooping judge re-enters through a door directly in front of her. She is the focus of the room’s attention as she looks up at him, her eyes fixed and unflinching. To Judge Stephen’s left a dark curtain ripples before being drawn to one side. Twelve black-coated men file into the jury box. It has taken them just forty-three minutes. She wonders whether any of them will dare to turn towards her. She is determined not to look away.

Dust motes dance in the light slanting from the windows before a cloud blots out the rays. Blown by a sharp wind, raindrops scatter against the glass skylight above her. There are seconds, then, of silence.

She hears the clerk ask his final question.

She straightens her back in the chair, feels the bare board beneath her feet, tries to raise her chin.

It is time.

ONE

CHAPTER 1

March 1889

Whenever the doorbell rings I feel ready to faint for fear it is someone coming to have an account paid.

The pen had hovered for a moment above the letter while she considered.

When Jim comes home at night – she continued in her neat cursive script – it is with fear and trembling that I look into his face to see whether anyone has been to the office about my bills.

*

In one of Liverpool’s best suburban addresses, Florence Maybrick was lost in thought as she sat in a silk-covered chair before the wide bay window. The parlour was almost perfect: embossed wallpapers offset red plush drapes lined with pale blue satin; several small tables, including one with negro supports, displayed shiny ornaments. A thick Persian carpet deadened the tread of restless feet.

A letter recently addressed to her mother in Paris lay beside her. It contained little of the chatter of the old days – the reports of balls and dinners, of new dresses, of renewed acquaintances or the children. Instead, despite her effort to alight on a defiantly insouciant tone, it charted a newer reality of arguments, accusations and continuing financial anxiety.

In a while she would call Bessie to take it to the post. For the present her tapering fingers remained idle in the lap from which one of her three cats had lately jumped, bored by her failure to show it affection.

Today, the twenty-six-year-old was wonderfully put together, her clothes painstakingly considered if a little over-fussed. Loose curls, dark blonde with a hint of auburn, were bundled up at the back of her head and fashionably frizzed across her full forehead. Slim at the waist, wrists and ankles, but with softly voluptuous bust and hips, she was all sensuousness, with large blue-violet eyes that made her irresistibly charming and aroused protective instincts in men. Yet a lack of angle in the line of her jaw conspired against Florence being a beauty, and a careful observer might even have noticed a peculiar detachment about her, for the young American was impressionable and egotistical, worldly but not wise.

Her glance lingered on the Viennese clock on the mantelpiece and slid across the cool lustre of the pair of Canton porcelain vases. Through the broad archway, early spring blossoms had been gathered into cut-glass vases and set on the Collard & Collard piano. Further down was the dining room with its Turkey carpet, leather-seated Chippendale chairs and sturdy oak dining table spacious enough for forty guests.

Each of these formal public rooms opened on to a broad hall where double doors led to steps and a gravel sweep that snaked out towards substantial gates set into walls draped with ivy. At the back of the hall a dark-wood staircase rose to a half-landing where a stained-glass window scattered coloured drops of light about the walls and floors. A narrower set of stone steps went down to the flagged kitchen, servants’ dining room, scullery, pantry, china and coal stores and the washroom with its large copper tub.

The parlour fire smouldered. Occasionally a log resettled with a gentle plume of ash.

Outside, beyond lace-draped French windows, lawns reached down towards the river, covered by a layer of thick snow that muffled the memory of happier summers. A pair of peacocks high-stepped – screaming at the cartwheeling flakes – past shrubberies, flowerbeds and summerhouses, round a large pond and through the thickest drifts lumped over the long grass in the orchard. The chickens ruffled their feathers against the cold; in the kennels and stables the dogs and horses breathed white into the cold air. A fashionable three-seated phaeton was locked away in its shed, protected from the encroaching white.

Upstairs, on the first floor, was the Maybricks’ substantial master bedroom with its adjoining dressing room containing a single bed. Next door to it was a large, square guest room and, further along the corridor, a night nursery for the two children – seven-year-old James (known as Sonny or Bobo) and Gladys, who would soon turn three. A linen cupboard was at one end of the landing and a lavatory and bathroom at the other, along with a separate ‘housemaid’s closet’ with a large sink and shelves. On the second floor were lower-ceilinged rooms, a day nursery where the children took their lessons and three smaller bedrooms shared by the female staff – a cook, housemaid, parlour maid and the children’s nurse.

Battlecrease House spoke of prosperity and stability, proclaiming Florence and her solid English husband – twenty-four years her senior – to be an ambitious couple attuned to the envy game. It was a private, family space but also an assertion of their conformity to conventional taste and morality, a stage for the formal dinners and whist suppers that oiled the wheels of society and business. As Henry James’ Madame Merle noted, one’s house, one’s furniture, one’s garments, the books one reads, the company one keeps – these things are all expressive.

One half of a substantial, squarely built building divided into two separate homes, Battlecrease had been James’ choice. Next door lived the Steels: Maud and her solicitor husband Douglas. Over the road was the Liverpool Cricket Club, its spacious grounds ensuring that the plot was not overlooked – that it was private if not remote. Turn left from the driveway and narrow Riversdale Road soon joined broad Aigburth Road with its clusters of small shops: grocers, butchers and several chemists. Turn right instead, cross the bridge over a little railway line and the road ended with a fine view of the slate-grey Mersey, an expanse of river and sky raked by slanting light and bracing winds. On the far bank were the tree-studded hills of the Wirral.

Right on the border of the southern suburbs of Aigburth and Grassendale, the district was all fresh air, birdsong and a slow pace of life. Yet it took only half an hour to reach the heart of the robust city by train or carriage and servants and workers could easily grab a penny seat in the tram running down Aigburth Road.

Just five miles away, Liverpool – the principal city of Lancashire and known as ‘the Port of Empire’ – might have been another world. As the nation’s second most important city, goods and passengers crowded the shipping basins, warehouses and factories that lined the six miles of its industrialised shore. Mercantile ambition and civic power had triumphed here: wrought-iron lamp-posts stood sentinel on the corners of the main streets and grand new classical structures graced the city centre, including St George’s Hall (1838), the Walker Art Gallery (1874) and the County Sessions House (1884). For a swelling bourgeoisie clamouring for cultural pastimes there was a thriving Philharmonic Hall and Society, as well as an ever-growing number of theatres, concert and music halls, libraries and various other improvement societies.

Six hundred thousand souls called it home. A system of over two hundred horse-drawn trams ran on tracks down the centre of arterial roads and from its five railway termini lines radiated to the north, south and east. Streets had been re-developed for shops that offered the latest Paris fashions and everything an aspiring couple could need in order to make their lives appear ‘just so’. There was Lewis’s – one of the earliest department stores – as well as auction houses and salerooms. There was a thriving city press and W. H. Smith’s red carts dashed across the roads, piled high with the latest newspapers. Over whelmingly, there was noise and action: the shriek of trains pitted against the rumble of coal wagons, the tramp of policemen’s boots, the whir of machinery, the clatter of horses: what theLiverpool Review described as the roar of the great caravansary.

Alongside the city’s elegant late-Georgian districts Victorian terraces had multiplied and a string of urban parks, punctuated with developments of pretty detached villas, proclaimed the gentrification of the suburbs. By com parison, along the line of docks that described Liverpool’s western margin the smell of seawater mingled with the tang of creosote, sweat and smoke. Past tall stone buildings and warehouses bursting with tobacco, cotton and spices, an assortment of vehicles swerved through dense traffic. Extending for miles, the tall masts of boats pricked at the sky – their rigging slapping fractiously in the wind – while above them lowered the broad funnels of the transatlantic steamers delivering immigrants to England or waiting for the flood tide to transport passengers to the New World.

By the late 1880s other English ports were beginning to compete, but about a third of all the country’s business and almost all of her American trade still passed through Liverpool. As a result, alongside its middle-class entertainments, its concert halls and hospitals, the city was pitted with sugar refineries, iron and brass foundries, breweries, roperies, alkali and soap works, cable and anchor manufactories and tar and turpentine distilleries. Neighbouring collieries fuelled its industry. Canal and rail links with nearby Manchester boosted its wealth.

Liverpool’s connection with America’s Southern cotton growers was so close that the city had supported the Southern states during the American Civil War, hoisting Confederate flags on its public buildings. Cotton was the king: around six million bales arrived each year from America’s Atlantic and Gulf ports, accounting for almost half of Liverpool’s imports, destined for the forty million spindles and half a million looms of the Lancashire cotton mills. Bundled in the heat of the cotton fields, it was unloaded in a city where, during the autumn and winter, river fog slicked the cobbled streets and drizzle diffused the light from shop windows as pedestrians turned their shoulders to the squalls blown in from the sea.

The great industrial city was powerfully exciting, providing the opportunity to accumulate significant wealth and offering numberless chances for improvement. Yet its renaissance was rooted in the dirty profits of the slave trade and the place still had, for all its self-regard, its ambition and its pride, a rotten underbelly. Slums straggled back from the waterfront; ragged, malnourished and deformed children swarmed through shambolic rookeries and courts where forty families might be forced to share a single water tap and latrine, and where filth seeped into the walls. Regardless of the City Corporation’s vigorous attempts at slum clearance and the fact that it was the first both to appoint a Medical Office of Health and to establish district nurses, the bustle of commerce masked a city of extremes. Under the surface of thrusting progress, beneath the skin of propriety and manners, vicious poverty, a violent gang culture and physical suffering persisted. I had seen wealth. I had seen poverty, Richard Armstrong would write in 1890, but never before had I seen streets ... with all that wealth can buy loaded with the haunts of hopeless penury ... the gaunt faces of the poor, the sodden faces of the abandoned, the indifferent air of so many who might have been helpers and healers of woe.

Battlecrease House and suburban Aigburth were financed by the profits of this industrial trade but they stood apart from its poverty, providing protection from the distressing shadow of material want, the city’s stench as much as its noise and speed. Attuned to the distant boom of the ships’ blasts, to the ebb and flow of the mighty river that reflected and magnified the light, the only complaints here were from the mournful seagulls whose pulsing cries seemed unceasingly to stitch together the land, sea and sky.

*

Sitting in the Battlecrease parlour that Saturday morning, 16 March 1889, Florence felt suffocated. It wa...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherAbrams Press

- Publication date2015

- ISBN 10 1468311190

- ISBN 13 9781468311198

- BindingPaperback

- Edition number1

- Number of pages432

- Rating

Shipping:

US$ 5.63

From United Kingdom to U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Did She Kill Him?: A Victorian Tale of Adultery, Arsenic, and Murder I Victorian England

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Very Good. Did She Kill Him?: A Victorian Tale of Adultery, Arsenic, and Murder I Victorian England This book is in very good condition and will be shipped within 24 hours of ordering. The cover may have some limited signs of wear but the pages are clean, intact and the spine remains undamaged. This book has clearly been well maintained and looked after thus far. Money back guarantee if you are not satisfied. See all our books here, order more than 1 book and get discounted shipping. . Seller Inventory # 7719-9781468311198

Did She Kill Him?: A Victorian Tale of Adultery, Arsenic, and Murder I Victorian England

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Very Good. Shipped within 24 hours from our UK warehouse. Clean, undamaged book with no damage to pages and minimal wear to the cover. Spine still tight, in very good condition. Remember if you are not happy, you are covered by our 100% money back guarantee. Seller Inventory # 6545-9781468311198