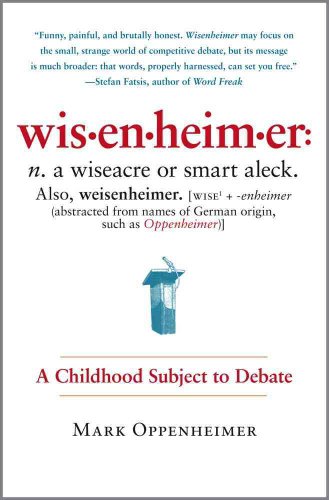

Wisenheimer: A Childhood Subject to Debate - Hardcover

Who knew big words and knew how to use them? Was he a charmer or an insufferable smart aleck—or maybe both? Mark Oppenheimer was just such a boy, his talent for language a curse as much as a blessing. Unlike math or music prodigies, he had no way to showcase his unique skill, except to speak like a miniature adult—a trick some found impressive but others found irritating. Frustrated and isolated, Oppenheimer used his powers for ill—he became a wisenheimer—pushing his peers and teachers away, acting out with prank phone calls, and worse. But when he got to high school, Oppenheimer discovered an outlet for his loquaciousness: the debate team.

This smart, funny memoir not only reveals a strange, compelling subculture, it offers a broader discussion of the splendor and power (including the healing power) of language and of the social and developmental hazards of being a gifted child. Oppenheimer’s journey from loneliness to fulfillment affords a fascinating inside look at the extraordinary subculture of world-class high-school debate and at the power of language to change one’s life.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Oppenheimer writes movingly about the art of rhetoric, of his passion for it, and of the inspiration he derived from debating and watching others do it. This smart, funny memoir not only reveals a strange, compelling subculture, it also offers a broader discussion of the splendor and power of language and of the social and developmental hazards of being a gifted child. Finally, it looks with hope at our present age, in which oratory is once again an important force in American culture.

Revealing, touching, and entertaining, Wisenheimer offers a brilliant portrait of the rarefied world of high school and college debate--and of what it's like to grow up talkative in America.

A Conversation with Author Mark Oppenheimer

Q: What was the first sign that you were going to be a "different" kind of kid?

A: Like a lot of children, I talked early and had a very big vocabulary. I think what made me a bit different was that I couldn't stop talking, and I wanted to talk instead of doing just about anything else. From the time I was about one, I took a strong pleasure in words, not just as a means of communicating but as these cool little objects that could be put to use. When I was about four, I walked around a clothing boutique asking all the women shoppers how old they were--that was the kind of thing that got me in trouble. Although, as the owner said to my dad, "At least he wasn't asking their weight."

Q: You say in the book that you had a hard time with certain teachers. What happened, and why do you think that was?

A: Some teachers just didn't like that I would correct their grammar or their spelling. In fifth grade, one teacher crossed out the word "specific," which I had used in an assignment, and wrote "pacific." When I told her that I meant "specific," she said, sweet as could be, "Honey, there is no word 'specific.' You mean 'pacific.'" And that bothered me, not just because it obviously undermined my confidence that she had anything to teach me, but also because I had a strong moral sense that my fellow students would be misled. I thought I had to look out for them. Then, one teacher in particular, who was young and pretty insecure in the classroom, really didn't like me--she could be very cruel. The incident I recount in the book is when she took a poll of all my fellow students, asking who among them liked me! This was meant to put me in my place, I guess. Hard to believe that really happened, but it did. She later had a nervous breakdown and threatened to kill the principal, for what it's worth.

Q: Did you ever feel, as a kid, that your mouth kept you from making and keeping friends?

A: Sure. Anything that makes a student stand out can work against him. Or her, I might add--I actually think life is far harder for nerdy girls, because society has more rigid expectations for them. But one of the points I make in the book is that the United States has a lot of organized activities for math, science, or music prodigies, but really nothing to occupy a word nerd--at least not until high school, when debate teams kick in.

Q: What did discovering Judy Blume's fictional Tony Miglione do for you? And Alex P. Keaton on Family Ties? How did they affect you?

A: Tony Miglione was nearly my downfall--I imitated the prank phone calls he and his friend Joel make, and I was nearly arrested. The police paid my mother a call, I was pulled out of school. It was a very ugly episode in my childhood, and I won't say more here, because I shed all those tears writing it up for the book! But Alex P. Keaton--God bless him. That TV character made the word nerd seem cool. I watched Family Ties religiously, and if I ever meet Michael J. Fox I will give him an earful about what his role meant to me. It meant a great deal, truly.

Q: You first debated at age 12 with the Wilbraham & Monson Academy high school team--and your partner was an 18-year-old Hendrix-burning-the-guitar-era metalhead. What was your first tournament like?

A: Yeah, I was quite lucky. For junior high, my parents sent me to a grades 7-12 school, and the high school had a debate team. The kids on the debate team were basically a bunch of rejects (and I mean that in a nice way!): they were stoners, theater kids, other people who didn't fit into the jock culture of the school. And as a 12-year-old I got paired with this guy Todd, a senior who smoked cigarettes and played guitar. He was actually nice guy, pretty shy. I think he scared me and I scared him. But we won most of our rounds that winter.

Q: Then, you got thrown in a river. What happened?

A: You had to bring that up? I was reprising some of my Tony Miglione, prank-phone-call type stuff, and this other senior on the debate team caught on that I was harassing him. He was really mean, and I was scared of him, so I acted out the way I knew how. And he threw me in the Rubicon, which was this little creek that ran through campus. I went back to the scene of the crime not long ago, and the Rubicon was dried up. Damned global warming.

Q: Graduating to prep school level debate, you made a near-fatal error in your first prep school tournament--pulling at the judges' heart-strings too much. What did you learn from that? How did you recover?

A: Initially, I coasted on just being articulate, in this very dramatic way. Over time, however, I learned that you had to have good argumentation, too. It's always a balance, I think, between eloquence and argument. You need both. Most American high school debaters have a lot of argument, but aren't very eloquent. I had the opposite problem. (Of course, most of our politicians have neither!)

Q: What were some other crucial debating skills and strategies you learned along the way?

A: My coach, Mr. Robison, to whom the book is dedicated, had gone to graduate school in philosophy, and he would talk to us about the importance of really using philosophical concepts. It was from him, not from any classroom, that I first learned about utilitarianism, Kantian ethics, and other ideas like that. I owe him a lot, not just because he taught me how to succeed in debate but also because he shaped my thinking in so many ways. Also, his father was a Baptist minister, so we would talk about religion--and now I write about religion for the New York Times.

Q: What was the best part of debate for you?

A: The community! Here were other word nerds, other kids who liked to argue. Through debate I met kids like me from about 20 states and 10 countries. It was amazing. Plus, I met one very cute girl at a debate tournament, although that ended disastrously, as anyone reading the book will see. I wince just thinking about it.

Q: Why didn't you make the debate team at Yale your freshman year?

A: I had a lot of conspiracy theories at the time, but probably I was just too cocky. Of course, I will never truly know, will I?

Q: When you did, eventually, make the team, how was college debate--Yale, in particular, as a member of American Parliamentary Debate Association (APDA)--different from your high school form of debate?

A: APDA, which includes most of the Ivy League teams plus other schools, like Stanford and the University of Chicago, was riddled with corruption, because all the judging was done by other students. So if you lost to a Princeton debater one week, you might be judging him--and able to settle the score--the next. Plus, nobody really took the topics seriously. They just ignored the topic and debated whatever they wanted. It was sick, twisted, and bizarre.

Q: How did your love of debate and oratory lead you to study religion?

A: I think the common denominator was preaching. Who are the best public speakers in America? Preachers. Because, let's face it, most of our politicians can't speak their way out of a paper bag.

Q: Are you a lot like the child you used to be?

A: Well, my editors still get on my case about using words nobody understands. In an article I just wrote for the Times, my editor queried "shtiebel" and "elevenses." (You can look them up.) But in some ways I am pretty different. I have more self-confidence in other areas of life, so I am less attached to proving how articulate I can be. Then again, I write for a living, so who am I kidding? OK, gotta go have elevenses now. Talk to you later.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherFree Press

- Publication date2010

- ISBN 10 1439128642

- ISBN 13 9781439128640

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages256

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Wisenheimer: A Childhood Subject to Debate

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Dust Jacket Condition: New. First Edition; First Printing. Book and DJ New. NO notes or other names, NO markings. DJ not clipped ($25) ; Inscribed and signed by author at title page in 2020.; 237 pages; Signed by Author. Seller Inventory # 68205

Wisenheimer: A Childhood Subject to Debate [Hardcover] Oppenheimer, Mark

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.65. Seller Inventory # Q-1439128642