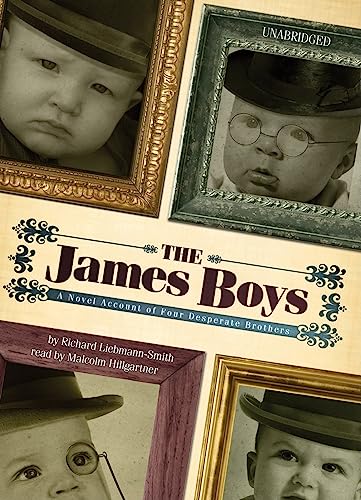

The James Boys: A Novel Account of Four Desperate Brothers

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Richard Liebmann-Smith, a former editor of The Sciences magazine, is co-creator an animated Comedy Central TV show. He has written for the New Yorker and National Lampoon, among others. He lives in New York City.

At four-forty-five on the afternoon of July 7, 1876, the Number 4 Missouri Pacific Express, made up of two sleeping cars, three day coaches, and two baggage cars, pulled out of Kansas City, headed east for St. Louis. Among the passengers aboard that day, along with the usual contingent of rough-clad farmers, itinerant preachers, and high- collared Chicago drummers, was Henry James, who was completing a tour of the western states and territories he had embarked on six weeks earlier at the behest of John Hay, editor of The New York Tribune. Such journalistic journeys had become all the rage ever since the great linkage of the nation's eastern and western rail lines in 1869, opening the continent for commerce, settlement, and an exotic new brand of tourism that the railroad companies and newspapers hoped might appeal to wealthy Americans jaded with the fashionable Grand Tour of Europe.

In fact, Henry was not so much completing his western tour as aborting it-cutting short his travels, as he complained to his editor, on account of "excruciating gastric distress." Indeed, the Jamesian digestive apparatus had been in chronic disrepair ever since its exposure a month earlier to the cuisine of St. Louis, a series of "desperate variations upon the inherently unpromising culinary theme of fried catfish." To make matters worse, Henry's back was killing him. In the terminology of today's psychiatry, the Jameses were notorious somaticizers: Their psychological conflicts often manifested in the form of such physical symptoms as painful digestive disturbances, crippling constipation, mysterious visual weaknesses, and blazingly aching backs. (William James, fresh out of the Harvard medical school, diagnosed his brother's spinal symptoms as "dorsal insanity.") In this instance, we might suspect that an underlying reason for Henry's distress-and Henry James was never one to deny any reason its fair weight and then some-was that the young author had come to realize he had neither talent nor taste for newspaper writing. "Try as he might," wrote his biographer Leon Edel, "Henry James could never speak in the journalistic voice. It was as if a man, fluent, suddenly reduced himself to a stutter." In his own mind, James was destined to be a great literary artist, not a newspaper hack, and his true vocation would hardly suffer a whit, he no doubt told himself, if he were never to describe another thundering herd of bison, painted Red Indian, or towering Rocky Mountain. Mark Twain could have the lot. Henry's idea of "roughing it" was any hotel under a two-star rating, and the truth, which must have been painfully apparent to him as he stared out over the western Missouri landscape described by Jesse James's biographer T. J. Stiles as resembling "a rug pushed into a corner: rumpled, wrinkled, rippled with ravines," was that all of that open space-those endless empty miles with scarcely a shanty, much less a café or cathedral to break the sheer geology of it all-had literally made him sick.

Fortunately, the interior scenery of the coach was to prove far more to Henry's taste: Across the aisle from the writer sat a young woman who would soon introduce herself as Elena Phoenix and who would come to play a singularly significant role in the lives of the entire James clan. Though he scarcely could have been characterized as a ladies' man in the vulgar, predatory sense, Henry James was nonetheless a connoisseur of what he once described as the "more complicated" sex. Even at this early stage of his literary career, he had long since determined that womanhood, particularly the freshly emerging American strain, was to be a salient subject of his work. ("My Bible is the female mind," declares a diarist in Henry's 1866 tale "A Landscape Painter.") Like Winterbourne, the protagonist of Daisy Miller, Henry had a great relish for feminine beauty; he was addicted to observing and analyzing it, and though the features of the specimen presently under his scrutiny were partially obscured by the magazine in which she was engrossed, he could not have helped but discern that the coils of her golden tresses framed a face of remarkable beauty-though it was a beauty, he might have been compelled to note, of the sort more properly designated "handsome" than "pretty." If contemporary photographs of Elena are a suitable guide, Henry's practiced eye doubtless would have registered a slightly too firm set to her mouth, which seemed to war with the sensuous fullness of her lips, and that the angles of her glowing cheeks were perhaps a shade too sharply chiseled for one of the "gentle gender." Nonetheless, the softness of her sex and age-she was then only twenty-two-no doubt lent a sweetness and vulnerability to her patrician countenance that served to take the chill off its sheer sculptural achèvement.

On this occasion, the softer aspect of her being was accentuated by a fashionable mauve frock, which blossomed with fantastic frills and flounces and from which a daring flash of lemon-yellow petticoat peeped fetchingly at the ankle. Her narrow waist was garnished with a crimson sash, and around her neck, falling low over her rounded bosom, hung a double strand of glowing amber beads. But more striking to Henry James than the young woman's fine features and modish attire would have been a certain larger-than-life aspect of her bearing, an altogether "finished" quality proclaiming the presence of a public personage. She might have seemed to him-in a phrase he would later apply to Isabel Archer in The Portrait of a Lady-to have "the general air of being someone in particular." Here, he could have been moved to speculate, was a talented diva bearing the bright torch of the operatic art to the benighted provinces of the West, or perhaps a celebrated comedienne-a radiant Juliet or heartrending Camille honing her art on the coarser sensibilities of the hinterlands before essaying to captivate the more sophisticated audiences of the great metropoli back east.

Yet it was neither her elegant apparel, nor her exquisite facial contours, nor even her "general air," to which his gaze was ultimately drawn, but rather to the reading matter upon which her own attention appeared so fiercely fixed. Henry could not have helped but recognize the familiar typography of The Atlantic Monthly-indeed, one of the issues in which his first novel, Roderick Hudson, had recently been serialized.

In his later years, after the turn of the century, James would be widely revered as "The Master," with an imposing oeuvre comprising dozens of novels, scores of novellas, and hundreds of short stories. But in that centennial summer of 1876, all of this was far ahead of him and by no means assured as his destiny. He was still in the thrall of what he once called "the hungry futurity of youth," and we can only imagine the maelstrom of emotion generated by the fledgling author's realization that this lovely young woman was in fact perusing his very own words. Her lips moved silently, voluptuously forming the shape of his every syllable-a reading habit he might normally have deemed jejune but which, considering the exquisite syllables in question (to say nothing of the exquisite lips), must have struck him as infinitely charming.

To achieve a better view, he cranked his reclining chair to its forward-most position so energetically that he may have feared pitching himself headlong into the aisle. Sensing the high voyeuristic voltage being generated across the way, the young woman lifted her eyes to intercept the writer's intense gaze with a cool, quizzical look of her own. (Though proper ladies of the era were conventionally admonished never to encourage "acquaintanceship" with strangers on trains, Elena was hardly one to abide by the rigid strictures of mid-Victorian propriety.)

"I beg your pardon, sir?"

Henry James colored as if caught in some particularly unclean act.

"I gather from your, ah, oscillations," she went on, "that you must be exceedingly interested in my magazine." She held out The Atlantic, offering it across the aisle. "Would you care to peruse it at closer range?"

"I . . . I . . . I . . . no . . . I . . . " Henry stammered, for however gracefully his words may have glided across the smooth plane of the printed page, in the more turbulent atmosphere of the three- dimensional world, they often flapped wildly about, like chimney swallows flushed into a drawing room.

"Well, if you don't care to read it, then I would be most grateful if you would kindly desist from staring at it so." The young woman delivered this remonstrance with a prim nod and a satisfied half- smile, feeling, as she later recorded in her diary, in equal measure pleased and amused by the firmness of tone she was taking with this imposing stranger. James was now thirty-three and, by at least one account, a fine figure of a man: "He had mildly swelled, not to fatness, not to stoutness, but well nigh to the brink of plumpness," wrote William H. Huntington, a colleague at the Tribune. "Also hath whiskers, full but close trimmed. By reason of these fulfillments . . . he has much more waxed in good lookingness, and is in his actual presentment (specially qua head) a notably finer person than one in the next 10,000 of handsome men."

All these fine fulfillments notwithstanding, at this moment Henry appeared to Elena "for all the world like a schoolboy harshly scolded" as he hurriedly averted his gaze and made an elaborate show of scribbling in the pages of the notebook on his lap.

"Really," the young woman insisted, "I'd be most happy to let you have the magazine. But I simply cannot abide anyone reading over my shoulder. It gives me the willies."

This remark, accompanied by an exaggerated mock shudder that no doubt struck Henry-especially in conjunct...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherBlackstone Audiobooks, Inc.

- Publication date2008

- ISBN 10 1433215403

- ISBN 13 9781433215407

- BindingAudio CD

- EditorReader: To Be Announced

- Rating

Shipping:

US$ 3.99

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The James Boys: A Novel Account of Four Desperate Brothers - Audio Book on CD

Book Description Audio CD Plastic Box. Condition: Very Good. Dust Jacket Condition: Very Good. Audio book on CD. This audio book has 8 CD's in very good condition with a library's circular sticker on each one. The plastic case is in very good condition with some stickers on it. This book is read by Malcolm Hillgartner and lasts about 9.5 hours. Audio CD Ex-Library. Seller Inventory # 007029

The James Boys: A Novel Account of Four Desperate Brothers

Book Description AUDIO CD. Condition: Good. 8 AUDIO CDs withdrawn from the library collection. Library sticker and stamp. We will take care to polish the Audio CDs for a clear listening experience. Enjoy this reliable AUDIO CD performance. Seller Inventory # ORIGINALCDs 91