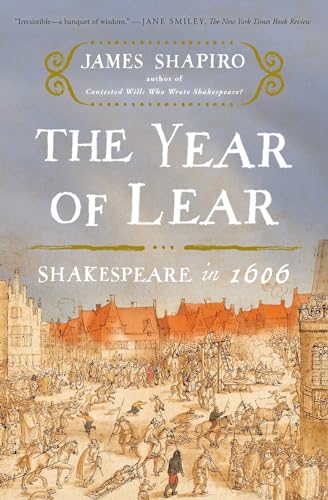

The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606 - Softcover

In the years leading up to 1606, Shakespeare’s great productivity had ebbed. But that year, at age forty-two, he found his footing again, finishing a play he had begun the previous autumn—King Lear—then writing two other great tragedies, Macbeth and Antony and Cleopatra.

It was a memorable year in England as well—a terrorist plot conceived by a small group of Catholic gentry had been uncovered at the last hour. The foiled Gunpowder Plot would have blown up the king and royal family along with the nation’s political and religious leadership. The aborted plot renewed anti-Catholic sentiment and laid bare divisions in the kingdom.

It was against this background that Shakespeare finished Lear, a play about a divided kingdom, then wrote a tragedy that turned on the murder of a Scottish king, Macbeth. He ended this astonishing year with a third masterpiece no less steeped in current events and concerns: Antony and Cleopatra.

“Exciting and sometimes revelatory, in The Year of Lear, James Shapiro takes a closer look at the political and social turmoil that contributed to the creation of three supreme masterpieces” (The Washington Post). He places them in the context of their times, while also allowing us greater insight into how Shakespeare was personally touched by such events as a terrible outbreak of plague and growing religious divisions. “His great gift is to make the plays seem at once more comprehensible and more staggering” (The New York Review of Books). For anyone interested in Shakespeare, this is an indispensable book.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

THE KING’S MAN

In the summer of 1605 John Wright began selling copies of a newly printed play called The True Chronicle History of King Leir, which had first been staged around 1590. Not long after, William Shakespeare, who lived just a short stroll from Wright’s bookshop, picked up a copy. A few years earlier Shakespeare had moved from his lodgings in Southwark, near the Globe Theatre, to quarters in a quieter and more upscale neighborhood, on the corner of Silver and Muggle Streets in Cripplegate. His landlords were Christopher and Marie Mountjoy, Huguenot artisans who made their living supplying fashionable headwear for court ladies. The walk from his new lodgings to Wright’s bookshop took just a few minutes. Crossing Silver Street, Shakespeare would have passed his parish church, St. Olave’s, before heading south down Noble Street toward St. Paul’s Cathedral, passing Goldsmiths’ Hall as Noble Street turned into Foster Lane, emerging onto the busy thoroughfare of Cheapside. With Cheapside Cross to his left, and St. Paul’s and beyond it the Thames directly ahead, Shakespeare would have turned west, passing St. Martin’s Lane and then the Shambles, home to London’s butchers. Christ Church was now in sight, and just beyond it Wright’s shop, abutting Newgate market.

The advertisement on the title page of King Leir—“As it hath been divers and sundry times lately acted”—made it sound like a recent play, an impression reinforced by the quiet omission of who wrote and performed it. But Shakespeare knew that it was an old Queen’s Men’s play and probably also knew (though we don’t) who had written it. The Queen’s Men were a hand-picked all-star troupe formed under royal patronage back in 1583. For the next decade they were England’s premier company, touring widely, known for their politics (patriotic and Protestant), their didacticism, and their star comedian, Richard Tarleton. If he wasn’t busy acting that day in another playhouse, Shakespeare may have been part of the crowd that paid a total of thirty-eight shillings to see the Queen’s Men stage King Leir at the Rose Theatre in Southwark on April 6, 1594 (in coproduction with Lord Sussex’s Men), or part of the smaller gathering two days later for a performance that earned twenty-six shillings—solid though not spectacular box office receipts.

Looking back, Shakespeare would have recognized that their appearance at the Rose marked the beginning of the end for the Queen’s Men, who the following month sold off copies of some of their valuable play-scripts to London’s publishers, then took to the road, spending the next nine years touring the provinces until, upon the death of Queen Elizabeth, they disbanded. That year also marked the ascendancy of the company Shakespeare had recently joined as a founding shareholder, the Chamberlain’s Men, who soon succeeded the Queen’s Men as the leading players in the land, a position they had held ever since. King Leir had been among the plays the cash-poor Queen’s Men had unloaded in 1594, and Edward White, who bought it, quickly entered his right to publish the play in the Stationers’ Register. But for some reason, perhaps sensing that the play had little prospect of selling well, White never published it. Over a decade would pass before his former apprentice John Wright obtained the rights from him and the play finally appeared in print.

One of the many towns where the Queen’s Men had performed in the late 1580s had been Stratford-upon-Avon. In the absence of any information about what Shakespeare was doing in his early twenties, biographers have speculated that he may have begun his theatrical career with this company, perhaps even filling in for one of the Queen’s Men, William Knell, killed in a fight shortly before the troupe was to perform in Stratford in 1587. It’s an appealing story—something, after all, must have brought him from Stratford to London—but there’s no evidence to substantiate it, nor is there any that would confirm that Shakespeare briefly acted with or wrote for this veteran company. But what is certain from the evidence of his later work is that he was deeply familiar with their repertory.

Scholars can identify with confidence fewer than a dozen plays, mostly histories, performed by the Queen’s Men during their twenty-year run. Several of their titles will sound familiar: The True Tragedy of Richard the Third, The Troublesome Reign of King John, and The Famous Victories of Henry the Fifth. A defining feature of Shakespeare’s art was his penchant for overhauling the plots of old plays rather than inventing his own, and no rival company provided more raw material for Shakespeare than the Queen’s Men. He absorbed and reworked their repertory in a series of history plays from the mid to late 1590s now familiar to us as Richard the Third, King John, the two parts of Henry the Fourth, and Henry the Fifth. Shakespeare’s attitude to the Queen’s Men was surely ambivalent. Their plays, which likely thrilled and inspired him in his formative years as playgoer, actor, and then playwright, had stuck with him. Yet he also would have recognized that their jingoistic repertory had become increasingly out of step with the theatrical and political times.

Shakespeare was a sharp-eyed critic of other writers’ plays and his take on the Queen’s Men’s repertory could be unforgiving, rendering these sturdy old plays hopelessly anachronistic. For a glimpse of this we need only recall his parody of an unforgettably bad couplet from their True Tragedy of Richard the Third: “The screeking raven sits croaking for revenge / Whole herds of beasts come bellowing for revenge.” These lines from the old play, whose awfulness had clearly stuck with Shakespeare, resurface years later when Hamlet, interrupting the play-within-the-play and urging on the strolling players, deliberately mangles the couplet: “Come, ‘the croaking raven doth bellow for revenge’” (3.2.251–52). At best this was a double-edged tribute, reminding playgoers of the kind of old-fashioned revenge drama they once enjoyed while showing how a naturalistic revenge play such as Hamlet had supplanted the dated and over-the-top style of the Queen’s Men.

Six years had passed since Shakespeare had last refashioned a Queen’s Men’s play in Henry the Fifth, a brilliant remake of their popular The Famous Victories of Henry the Fifth. If anything, the pace of change in those intervening years, especially the last three, had wildly accelerated. The Elizabethan world that had produced King Leir and in which the play had once thrived, like the playing company that had performed it, was no longer. But these years had enabled Shakespeare, as part owner of his playhouse and shareholder in his acting company, to prosper financially. When Wright began selling copies of King Leir in July of 1605 (two months usually lapsed between the time a book was registered and sold, and he had registered it in May), Shakespeare was likely away in Stratford-upon-Avon to close on a large real estate deal, so he couldn’t have picked up a copy until his return to London.

King Leir, like so many histories and tragedies of the 1590s, was fixated on royal succession. These plays spoke to a nation fearful of foreign rule or the outbreak of civil war after its childless queen’s death. For a decade that stretched from Titus Andronicus and his Henry the Sixth trilogy through Richard the Third, King John, Richard the Second, the two parts of Henry the Fourth, Henry the Fifth, Julius Caesar, and Hamlet, Shakespeare displayed time and again his mastery of this genre, exploring in play after play who had the cunning, wit, legitimacy, and ambition to seize and hold power. Those concerns peaked in the opening years of the seventeenth century as the queen approached her end, but vanished after 1603, when King James VI of Scotland, who was married and had two sons and a daughter, succeeded peacefully to the throne of England. There would be no Spanish invasion and no return to the kind of civil strife that had torn the land apart in the late fifteenth century. In an unusually explicit allusion to the political moment, Shakespeare writes in Sonnet 107 shortly after James’s accession that:

The mortal moon hath her eclipse endured,

And the sad augurs mock their own presage;

Incertainties now crown themselves assured,

And peace proclaims olives of endless age.

(Sonnet 107, 5–8)

The language is elliptical but the meaning clear enough: all those anxious predictions that preceded the eclipse of Elizabeth—that “mortal moon”—were misplaced; the crowning of the new king who promoted himself as a peacemaker had put an end to these “Incertainties.”

But other uncertainties remained. The period leading up to and following the change in regime appeared less smooth in retrospect than Sonnet 107 would on its surface suggest, for the nation and for Shakespeare professionally. The Chamberlain’s Men, now established at the Globe, found themselves facing stiffer competition than ever. Back in 1594 there had been only three permanent outdoor playhouses in London: the Theatre and the Curtain in Shoreditch, and the Rose on Bankside. Since then, new theaters continued to sprout around the City, competing for the pennies and shillings of London’s playgoers. Spectators were now flocking to see the Admiral’s Men at the Fortune Theatre (to the northwest, in the parish of St. Giles without Cripplegate), as well as to see Worcester’s Men perform at the Boar’s Head Inn (in Whitechapel), and to playhouses at St. Paul’s and Blackfriars, smaller indoor sites where boy companies performed plays by London’s edgier young dramatists. Aging public playhouses—the Curtain and the Swan in Southwark near Paris Garden Stairs—also peeled away customers.

Other and unexpected threats to the prosperity of Shakespeare and his fellow shareholders soon emerged. In early 1603, their influential patron, the Lord Chamberlain George Carey (second cousin to Queen Elizabeth), became seriously ill. More bad news followed. First came a Privy Council announcement on March 19, 1603, that because of concerns about civil unrest as Elizabeth lay dying, all public performances were canceled “till other direction be given.” News the following week of the queen’s death and the declaration that the King of Scots was now King of England as well, while reassuring the English that regime change would not be bloody, also meant that during this mourning period the playhouses were unlikely to open anytime soon. London’s playing companies must have been rocked by the next piece of disturbing news, as they waited to see how supportive of the theater King James would be. One of James’s first royal proclamations, on May 7, 1603, was to ban performances on the Sabbath. It was a punishing decree that cut into theatrical profits, for Sunday was the only day of the week that most playgoers weren’t laboring at work. Was this merely a sop to theater-hating Puritans or was it a sign that the new king saw little value in public theater?

The drumbeat of setbacks for Shakespeare and his company continued. King James didn’t wait for the ailing George Carey to die before replacing him as Lord Chamberlain. This meant that Shakespeare was no longer a Chamberlain’s Man, merely the servant of the disempowered Carey (who passed away in early September). The theater companies were facing their own succession struggle, one that would have to be resolved in the wake of the national one. At stake were royal patronage and the chance to be favored at court. It could not have been reassuring that the Earl of Nottingham, patron of their longtime rivals the Admiral’s Men, had secured a place in the new monarch’s inner circle.

Other unexpected and nagging threats emerged as the change in government encouraged those who wanted a share of the lucrative business of staging plays. Richard Fiennes, an aristocrat badly in need of money, proposed that in exchange for an annual payment of forty pounds he be awarded a patent allowing him to collect a poll tax of “a penny a head on all the playgoers in England.” Fiennes argued that since playgoing was a voluntary activity (much like what the king himself had deemed the “vile custom of tobacco taking”), it could be regulated and taxed by the state, and he would be happy to pay for overseeing that activity in exchange for a hefty cut of box office receipts. Since admission to the public playhouses started at a penny, Fiennes’s proposal was outrageously greedy. Luckily for London’s actors, nothing came of this nor of another proposal not long after from the other end of the social ladder, by a disabled veteran of the Irish wars, Francis Clayton. Fiennes had hoped to obtain a royal patent to tax playgoers; Clayton appealed to Parliament to tax performances, seeking for himself a “small allowance of two shillings out of every stage play that shall be acted . . . to be paid unto me or my assigns during my life by the owners and actors of those plays and shows.” It must have struck the players as absurd: anyone with a scheme and some political connections could submit a plan to cut into their hard-earned profits. Fiennes’s and Clayton’s proposals—although they went nowhere—were one more headache for Shakespeare and his fellows, vulnerable at this time of transition and of freewheeling and often unpredictable political largess.

Then, suddenly, came news that profoundly altered the trajectory of Shakespeare’s career: King James chose Shakespeare and his fellow players as his official company. After May 19, 1603, Shakespeare and eight others were to be known as the King’s Men, authorized to perform not only at the court and the Globe but also throughout the realm, if they wished to tour. It was more than a symbolic title; Shakespeare was now a Groom of the Chamber, and he and the other shareholders were each issued four and a half yards of red cloth for royal livery to be worn on state occasions.

Exactly how and why Shakespeare’s company was elevated to the position of King’s Men has never been satisfyingly explained. Their talent and reputation surely played a part. So too did a little-known English actor named Laurence Fletcher. Fletcher had spent time acting in Scotland, where King James had come to know and like him. This relationship accounts for why Fletcher’s name appears first, right before Shakespeare’s, in the list of those designated as the King’s Men, though he had never been affiliated with the company before this. Fletcher was merely a player; though a valuable go-between, he could not, by himself, have been responsible for Shakespeare’s company’s swift promotion. More powerful brokers were undoubtedly involved. One of them might have been the younger brother of their dying patron, Sir Robert Carey, who had ridden posthaste from London to Edinburgh to bring James word of Elizabeth’s death. Others might have been Shakespeare’s former patron, the Earl of Southampton, newly released from the Tower, or perhaps the Earl of Pembroke, an admirer of Richard Burbage and a patron of poets and artists. Mystery will always surround how Shakespeare and his fellow players were chosen to be the King’s Men. What matters is that it happened and that they had won their own succession struggle—and the plays that Shakespeare would subsequently write would be powerfully marked by this turn of events.

The King’s Men did not have much of a chance to celebrate their good fortune, for London was soon struck by a devastating outbreak of ...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherSimon & Schuster

- Publication date2016

- ISBN 10 1416541659

- ISBN 13 9781416541653

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages384

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606

Book Description paperback. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 1416541659-11-29068337

The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606 by Shapiro, James [Paperback ]

Book Description Soft Cover. Condition: new. Seller Inventory # 9781416541653

The Year of Lear Format: Paperback

Book Description Condition: New. Brand New. Seller Inventory # 9781416541653

Year of Lear : Shakespeare in 1606

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 26420014-n

The Year of Lear (Paperback)

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Paperback. Preeminent Shakespeare scholar James Shapiro, author of Shakespeare in a Divided America, shows how the tumultuous events in 1606 influenced three of Shakespeare's greatest tragedies written that year--King Lear, Macbeth, and Antony and Cleopatra. "The Year of Lear is irresistible--a banquet of wisdom" (The New York Times Book Review). In the years leading up to 1606, Shakespeare's great productivity had ebbed. But that year, at age forty-two, he found his footing again, finishing a play he had begun the previous autumn--King Lear--then writing two other great tragedies, Macbeth and Antony and Cleopatra. It was a memorable year in England as well--a terrorist plot conceived by a small group of Catholic gentry had been uncovered at the last hour. The foiled Gunpowder Plot would have blown up the king and royal family along with the nation's political and religious leadership. The aborted plot renewed anti-Catholic sentiment and laid bare divisions in the kingdom. It was against this background that Shakespeare finished Lear, a play about a divided kingdom, then wrote a tragedy that turned on the murder of a Scottish king, Macbeth. He ended this astonishing year with a third masterpiece no less steeped in current events and concerns: Antony and Cleopatra. "Exciting and sometimes revelatory, in The Year of Lear, James Shapiro takes a closer look at the political and social turmoil that contributed to the creation of three supreme masterpieces" (The Washington Post). He places them in the context of their times, while also allowing us greater insight into how Shakespeare was personally touched by such events as a terrible outbreak of plague and growing religious divisions. "His great gift is to make the plays seem at once more comprehensible and more staggering" (The New York Review of Books). For anyone interested in Shakespeare, this is an indispensable book. Shipping may be from multiple locations in the US or from the UK, depending on stock availability. Seller Inventory # 9781416541653

The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # DADAX1416541659

The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. 0.75. Seller Inventory # 1416541659-2-1

The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new1416541659

The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published 0.75. Seller Inventory # 353-1416541659-new

The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_1416541659