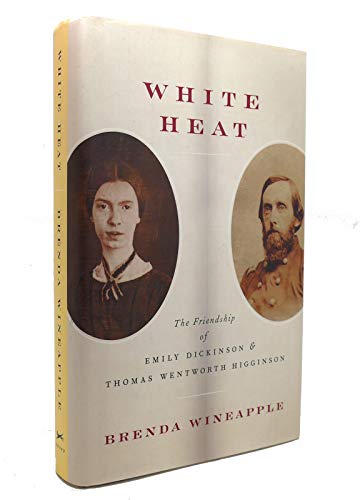

White Heat: The Friendship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson - Hardcover

Their friendship began in 1862. The Civil War was raging. Dickinson was thirty-one; Higginson, thirty-eight. A former pastor at the Free Church of Worcester, Massachusetts, he wrote often for the cultural magazine of the day, The Atlantic Monthly—on gymnastics, women’s rights, and slavery. His article “Letter to a Young Contributor” gave advice to readers who wanted to write for the magazine and offered tips on how to submit one’s work (“use black ink, good pens, white paper”).

Among the letters Higginson received in response was one scrawled in looping, difficult handwriting. Four poems were enclosed in a smaller envelope. He deciphered the scribble: “Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?”

Higginson read the poems. The writing was unique, uncategorizable. It was clear to him that this was “a wholly new and original poetic genius,” and the memory of that moment stayed with him when he wrote about it thirty years later.

Emily Dickinson’s question inaugurated one of the least likely correspondences in American letters—between a man who ran guns to Kansas, backed John Brown, and would soon command the first Union regiment of black soldiers, and the eremitic, elusive poet who cannily told him she did not cross her “Father’s ground to any House or town.”

For the next quarter century, until her death in 1886, Dickinson sent Higginson dazzling poems, almost one hundred of them—many of them her best. Their metrical forms were unusual, their punctuation unpredictable, their images elliptical, innovative, unsentimental. Poetry torn up by the roots, Higginson later said, that “gives the sudden transitions.”

Dickinson was a genius of the faux-naïf variety, reclusive to be sure but more savvy than one might imagine, more self-conscious and sly, and certainly aware of her outsize talent. “Dare you see a Soul at the ‘White Heat’?” she wondered. She dared, and he did.

In this shimmering, revelatory work, Brenda Wineapple re-creates the extraordinary, delicate friendship that led to the publication of Dickinson’s poetry. And though she and Higginson met face-to-face only twice (he had never met anyone “who drained my nerve power so much,” he said), their friendship reveals much about Dickinson, throwing light onto both the darkened door of the poet’s imagination and a corner of the noisy century that she and Colonel Higginson shared.

White Heat is about poetry, politics, and love; it is, as well, a story of seclusion and engagement, isolation and activism—and the way they were related—in the roiling America of the nineteenth century.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

This is my letter to the World

That never wrote to Me--

The simple News that Nature told--

With tender Majesty

Her Message is committed

To Hands I cannot see--

For love of Her--Sweet--countrymen--

Judge tenderly--of Me

Reprinted by Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Mabel

Loomis Todd in Emily Dickinson, Poems (1890)

Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?" Thomas Wentworth Higginson opened the cream-colored envelope as he walked home from the post office, where he had stopped on the mild spring morning of April 17 after watching young women lift dumbbells at the local gymnasium. The year was 1862, a war was raging, and Higginson, at thirty-eight, was the local authority on physical fitness. This was one of his causes, as were women's health and education. His passion, though, was for abolition. But dubious about President Lincoln's intentions--fighting to save the Union was not the same as fighting to abolish slavery-- he had not yet put on a blue uniform. Perhaps he should.

Yet he was also a literary man (great consolation for inaction) and frequently published in the cultural magazine of the moment, The Atlantic Monthly, where, along with gymnastics, women's rights, and slavery, his subjects were flowers and birds and the changing seasons.

Out fell a letter, scrawled in a looping, difficult hand, as well as four poems and another, smaller envelope. With difficulty he deciphered the scribble. "Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?"

This is the beginning of a most extraordinary correspondence, which lasts almost a quarter of a century, until Emily Dickinson's death in 1886, and during which time the poet sent Higginson almost one hundred poems, many of her best, their metrical forms jagged, their punctuation unpredictable, their images honed to a fine point, their meaning elliptical, heart-gripping, electric. The poems hit their mark. Poetry torn up by the roots, he later said, that took his breath away.

Today it may seem strange she would entrust them to the man now conventionally regarded as a hidebound reformer with a tin ear. But Dickinson had not picked Higginson at random. Suspecting he would be receptive, she also recognized a sensibility she could trust--that of a brave iconoclast conversant with botany, butterflies, and books and willing to risk everything for what he believed.

At first she knew him only by reputation. His name, opinions, and sheer moxie were the stuff of headlines for years, for as a voluble man of causes, he was on record as loathing capital punishment, child labor, and the unfair laws depriving women of civil rights. An ordained minister, he had officiated at Lucy Stone's wedding, and after reading from a statement prepared by the bride and groom, he distributed it to fellow clergymen as a manual of marital parity.

Above all, he detested slavery. One of the most steadfast and famous abolitionists in New England, he was far more radical than William Lloyd Garrison, if, that is, radicalism is measured by a willingness to entertain violence for the social good. Inequality offended him personally; so did passive resistance. Braced by the righteousness of his cause--the unequivocal emancipation of the slaves--this Massachusetts gentleman of the white and learned class had earned a reputation among his own as a lunatic. In 1854 he had battered down a courthouse door in Boston in an attempt to free the fugitive slave Anthony Burns. In 1856 he helped arm antislavery settlers in Kansas and, a loaded pistol in his belt, admitted almost sheepishly,

"I enjoy danger." Afterward he preached sedition while furnishing money and morale to John Brown.

All this had occurred by the time Dickinson asked him if he was too busy to read her poems, as if it were the most reasonable request in the world.

"The Mind is so near itself--it cannot see, distinctly--and I have none to ask--" she politely lied. Her brother, Austin, and his wife, Susan, lived right next door, and with Sue she regularly shared much of her verse. "Could I make you and Austin--proud--sometime--a great way off--'twould give me taller feet--," she confided. Yet Dickinson now sought an adviser unconnected to family. "Should you think it breathed--and had you the leisure to tell me," she told Higginson, "I should feel quick gratitude--."

Should you think my poetry breathed; quick gratitude: if only he could write like this.

Dickinson had opened her request bluntly. "Mr. Higginson," she scribbled at the top of the page. There was no other salutation. Nor did she provide a closing. Almost thirty years later Higginson still recalled that "the most curious thing about the letter was the total absence of a signature." And he well remembered that smaller sealed envelope, in which she had penciled her name on a card. "I enclose my name--asking you, if you please--Sir--to tell me what is true?" That envelope, discrete and alluring, was a strategy, a plea, a gambit.

Higginson glanced over one of the four poems. "I'll tell you how the Sun rose-- / A Ribbon at a time--." Who writes like this? And another: "The nearest Dream recedes--unrealize--." The thrill of discovery still warm three decades later, he recollected that "the impression of a wholly new and original poetic genius was as distinct on my mind at the first reading of these four poems as it is now, after thirty years of further knowledge; and with it came the problem never yet solved, what place ought to be assigned in literature to what is so remarkable, yet so elusive of criticism." This was not the benign public verse of, say, John Greenleaf Whittier. It did not share the metrical perfection of a Longfellow or the tiresome "priapism" (Emerson's word, which Higginson liked to repeat) of Walt Whitman. It was unique, uncategorizable, itself.

The Springfield Republican, a staple in the Dickinson family, regularly praised Higginson for his Atlantic essays. "I read your Chapters in the Atlantic--" Dickinson would tell him. Perhaps at Dickinson's behest, her sister-in-law had requested his daguerreotype from the Republican's editor, a family friend. As yet unbearded, his dark, thin hair falling to his ears, Higginson was nice looking; he dressed conventionally, and he had grit.

Dickinson mailed her letter to Worcester, Massachusetts, where he lived and whose environs he had lovingly described: its lily ponds edged in emerald and the shadows of trees falling blue on a winter afternoon. She paid attention.

He read another of the indelible poems she had enclosed.

Safe in their Alabaster Chambers--

Untouched by Morning--

And untouched by noon--

Sleep the meek members of the Resurrection,

Rafter of Satin and Roof of Stone--

Grand go the Years,

In the Crescent above them--

Worlds scoop their Arcs--

And Firmaments--row--

Diadems--drop--

And Doges--surrender--

Soundless as Dots,

On a Disc of Snow.

White alabaster chambers melt into snow, vanishing without sound: it's an unnerving image in a poem skeptical about the resurrection it proposes. The rhymes drift and tilt; its meter echoes that of Protestant hymns but derails. Dashes everywhere; caesuras where you least expect them, undeniable melodic control, polysyllabics eerily shifting to monosyllabics. Poor Higginson. Yet he knew he was holding something amazing, dropped from the sky, and he answered her in a way that pleased her.

That he had received poems from an unknown woman did not entirely surprise him. He'd been getting a passel of mail ever since his article "Letter to a Young Contributor" had run earlier in the month. An advice column to readers who wanted to become Atlantic contributors, the essay offered some sensible tips for submitting work--use black ink, good pens, white paper--along with some patently didactic advice about writing. Work hard. Practice makes perfect. Press language to the uttermost. "There may be years of crowded passion in a word, and half a life in a sentence," he explained. "A single word may be a window from which one may perceive all the kingdoms of the earth. . . . Charge your style with life." That is just what he himself was trying to do.

The fuzzy instructions set off a huge reaction. "I foresee that 'Young Contributors' will send me worse things than ever now," Higginson boasted to his editor, James T. Fields, whom he wanted to impress. "Two such specimens of verse came yesterday & day before--fortunately not to be forwarded for publication!" But writing to his mother, whom he also wanted to impress, Higginson sounded more sympathetic and humble. "Since that Letter to a Young Contributor I have more wonderful expressions than ever sent me to read with request for advice, which is hard to give."

Higginson answered Dickinson right away, asking everything he could think of: the name of her favorite authors, whether she had attended school, if she read Whitman, whether she published, and would she? (Dickinson had not told him that "Safe in their Alabaster Chambers" had appeared in The Republican just six weeks earlier.) Unable to stop himself, he made a few editorial suggestions. "I tried a little,-- a very little--to lead her in the direction of rules and traditions," he later reminisced. She called this practice "surgery."

"It was not so painful as I supposed," she wrote on April 25, seeming to welcome his comments. "While my thought is undressed-- I can make the distinction, but when I put them in the Gown--they look alike, and numb." As to his questions, she answered that she had begun writing poetry...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherKnopf

- Publication date2008

- ISBN 10 1400044014

- ISBN 13 9781400044016

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages432

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

White Heat: The Friendship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Book Description Condition: New. Buy with confidence! Book is in new, never-used condition. Seller Inventory # bk1400044014xvz189zvxnew

White Heat: The Friendship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Seller Inventory # 353-1400044014-new

White Heat: The Friendship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_1400044014

White Heat: The Friendship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard1400044014

White Heat: The Friendship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think1400044014

White Heat: The Friendship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover1400044014

White Heat: The Friendship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon1400044014

White Heat: The Friendship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks451935

White Heat: The Friendship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson Wineapple, Brenda

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # QCAD--0134

WHITE HEAT: THE FRIENDSHIP OF EM

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.65. Seller Inventory # Q-1400044014