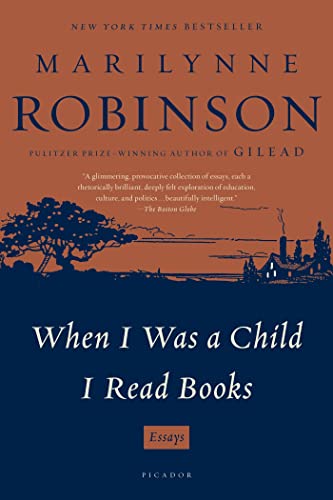

When I Was a Child I Read Books: Essays - Softcover

A New York Times Book Review Editors' Choice

A New York Times Bestseller

A New York Magazine Best Book of the Year

An Economist Best Book of the Year

Pulitzer Prize–Winning Author of Gilead

Marilynne Robinson has built a sterling reputation as not only a major American novelist but also a rigorous thinker and an incisive essayist. In this lucid but impassioned collection, Robinson expands with renewed vigor the themes that have preoccupied her work. When I Was a Child I Read Books tackles the charged political and social climate in this country, the deeply embedded role of generosity in Christian faith, and the nature of individualism and the myth of the American West. Clear-eyed and forceful as ever, Robinson demonstrates once again why she is regarded as one of our essential writers.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Marilynne Robinson is the author of the novels Housekeeping (FSG, 1981), Gilead (FSG, 2004), winner of the Pulitzer Prize, and Home (FSG, 2008), and three books of nonfiction, Mother Country (FSG, 1989), The Death of Adam (1998) and Absence of Mind (2010). She teaches at the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop.

Wondrous Love

I have reached the point in my life when I can see what has mattered, what has become a part of its substance—I might say a part of my substance. Some of these things are obvious, since they have been important to me in my career as a student and teacher. But some of them I could never have anticipated. The importance to me of elderly and old American hymns is certainly one example. They can move me so deeply that I have difficulty even speaking about them. The old ballad in the voice of Mary Magdalene, who “walked in the garden alone,” imagines her “tarrying” there with the newly risen Jesus, in the light of a dawn which was certainly the most remarkable daybreak since God said, “Let there be light.” The song acknowledges this with fine understatement: “The joy we share as we tarry there / None other has ever known.” Who can imagine the joy she would have felt? And how lovely it is that the song tells us the joy of this encounter was Jesus’s as well as Mary’s. Epochal as the moment is, and inconceivable as Jesus’s passage from death to life must be, they meet as friends and rejoice together as friends. This seems to me as good a gloss as any on the text that tells us God so loved the world, this world, our world. And for a long time, until just a decade ago, at most, I disliked this hymn, in part because to this day I have never heard it sung well. Maybe it can’t be sung well. The lyrics are uneven, and the tune is bland and grossly sentimental. But I have come to a place in my life where the thought of people moved by the imagination of joyful companionship with Christ is so precious that every fault becomes a virtue. I wish I could hear again every faltering soprano who has ever raised this song to heaven. God bless them all.

There is another song I think about—“I Love to Tell the Story.” The words that are striking to me are these: “I love to tell the story, for those who know it best / Seem hungering and thirsting to hear it like the rest.” This is true. Of course those who know it best would be those who, over time, put themselves in the way of hearing it. Nevertheless, if Western history has proved one thing, it is that the narratives of the Bible are essentially inexhaustible. The Bible is terse, the Gospels are brief, and the result is that every moment and detail merits pondering and can always appear in a richer light. The Bible is about human beings, human families—in comparison with other ancient literatures the realism of the Bible is utterly remarkable—so we can bring our own feelings to bear in the reading of it. In fact, we cannot do otherwise, if we know the old, old story well enough to give it a life in our thoughts.

There is something about being human that makes us love and crave grand narratives. Greek and Roman boys memorized Homer. This was a large part of their education, just as memorizing the Koran is now for many boys in Islamic cultures. And this is one means by which important traditions are preserved and made in effect the major dialects of their civilizations. Narrative always implies cause and consequence. It creates paradigmatic structures around which experience can be ordered, and this certainly would account for the craving for it, which might as well be called a need. Homer was taken to have great moral significance, as the Koran surely does, so there is nothing random in the choices civilizations make when literatures are sacred to them. I have a theory that the churches fill on Christmas and Easter because it is on these days that the two most startling moments in the Christian narrative can be heard again. In these two moments, narrative fractures the continuities of history. It becomes so beautiful as to acquire a unique authority, a weight of meaning history cannot approach. The stories really will be told again on these days because a parsing of the text would diminish the richness that, to borrow a phrase from the old Puritan John Robinson, shines forth from the holy Word. And everyone knows the songs, especially at Christmas, and becomes in that hour another teller of the story embedded in them. What child is this? A very profound question. Christmas and Easter are so full of church pageant and family custom that it is entirely possible to forget how the stories told on these two days did indeed rupture history and leave the world changed, implausible as that may seem. At the same time, they have created a profound continuity. If we sometimes feel adrift from humankind, as if our technology-mediated life on this planet has deprived us of the brilliance of the night sky, the smell and companionship of mules and horses, the plain food and physical peril and weariness that made our great-grandparents’ lives so much more like the life of Jesus than any we can imagine, then we can remind ourselves that these stories have stirred billions of souls over thousands of years, just as they stir our souls, and our children’s. What gives them their power? They tell us that there is a great love that has intervened in history, making itself known in terms that are startlingly, and inexhaustibly, palpable to us as human beings. They are tales of love, lovingly enacted once, and afterward cherished and retold—by the grace of God, certainly, because they are, after all, the narrative of an obscure life in a minor province. Caesar Augustus was also said to be divine, and there aren’t any songs about him.

We here, we Christians, have accepted the stewardship of this remarkable narrative, though it must be said that our very earnest approach to this work has not always served it well. There is a great old American hymn that sounds like astonishment itself, and I mention it here because even its title speaks more powerfully of the meaning of our narrative than whole shelves of books. It is called “Wondrous Love.” “What wondrous love is this that caused the Lord of bliss / to bear the dreadful cross for my soul?” If we have entertained the questions we moderns must pose to ourselves about the plausibility of incarnation, if we have sometimes paused to consider the other ancient stories of miraculous birth, this is no great matter. But if we let these things distract us, we have lost the main point of the narrative, which is that God is of a kind to love the world extravagantly, wondrously, and the world is of a kind to be worth, which is not to say worthy of, this pained and rapturous love. This is the essence of the story that forever eludes telling. It lives in the world not as myth or history but as a saturating light, a light so brilliant that it hides its source, to borrow an image from another good old hymn.

If we understand this to be true, what response do we make? How do we act? How do we live? We respond by loving the world God loves, presumably. But there is something about human beings that too often makes our love for the world look very much like hatred for it. Jesus said, “Do not think that I have come to bring peace on earth: I have not come to bring peace, but a sword” (Matthew 10:34). He said a number of things: “Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you” (Matthew 5:44), for example, and “Put your sword back in its place; for all who take the sword will perish by the sword” (Matthew 26:52). But for whatever reason—as a Calvinist I propose the reason might be our fallen state—human beings and Christians have found obedience to the commandment to love one another modified by the statement I quoted first, which does not have the form of a commandment, though it has been taken to have the force of one, and it has inspired the response “Send me, Lord,” with far more passion and consistency than the commandment tradition says is the last Jesus gave us, that we love one another (John 15:17). As a consequence, Christians have too often loved their enemies to death. Those enemies being, in the majority of cases, other Christians. The Inquisition is the most notorious case in point, but it is by no means isolated. Then as always the rationale was that those people with a different heritage or a different conception of the faith are not real Christians. They should be denounced, converted, or eliminated—for the sake of Christianity. And, fortunately, Jesus has provided us with that sword. This is a narrative that has been a major force in Christian history—God gives us the means and the obligation to smite his enemies. And we know who they are, so the story goes.

Jesus spoke as a man, in a human voice. And a human voice has a music that gives words their meaning. In that old hymn I mentioned, as in the Gospel, Mary is awakened out of her loneliness by the sound of her own name spoken in a voice “so sweet the birds hush their singing.” It is beautiful to think what the sound of one’s own name would be, when the inflection of it would carry the meaning Mary heard in the unmistakable, familiar, and utterly unexpected voice of her friend and teacher. To propose analogies for the sound of it, a human name spoken in the world’s new morning, would seem to trivialize it. I admire the tact of the lyric in making no attempt to evoke it, except obliquely, in the hush that falls over the birds. But it is nevertheless at the center of the meaning of this story that we can know something of the inflection of that voice. Christ’s humanity is meant to speak to our humanity. We can in fact imagine that if someone we loved very deeply was restored to us, the joy in his or her voice would anticipate and share our joy. We can imagine how someone bringing us wonderful news might say our name tenderly to soften the shock of our delight. The mystery of Christ’s humanity must make us wonder what of mortal memory he carried beyond the grave, and whether his pleasure at this encounter with Mary would have been shadowed and enriched by the fact that, not so long before, he had had no friend to watch with him even one hour. Scholars use the word “pericope”—where does a story begin and end? How much we would know about this dawn, this meeting of friends in a garden, if only we could hear his voice.

I tell my students, language is music. Written words are musical notation. The music of a piece of fiction establishes the way in which it is to be read, and, in the largest sense, what it means. It is essential to remember that characters have a music as well, a pitch and tempo, just as real people do. To make them believable, you must always be aware of what they would or would not say, where stresses would or would not fall. Those of us who claim to be Christian, Christ-like, generally assume we know what this word means, more or less—that we know the character of Christ. For Protestants, this understanding of him is mediated through the Bible. Our saints and doctors, however brilliant and heroic, are rarely looked to for wisdom or example. The figure of Christ is our authority. No distinction can be made between his character and his meaning. No distinction can be made between his character and the great narrative of his life and death. But the fact is that we differ on this crucial point, on how we are to see the figure of Christ.

This scene, the account of the first hours of the Resurrection, written two thousand years ago in a dialect of an ancient language, by whom and in what circumstances no one can really know, inevitably raises questions. How faithfully did the writer’s Greek approach the Aramaic of the original story—assuming that Mary would have told the story in Aramaic, and that Jesus would have spoken to her in that language? And how faithful have all the generations of translation been since then to the writer’s Greek? It must be said of the origins of this powerful text that the Lord made thick darkness its swaddling band.

We understand even the narrative of the origins of the narrative very differently. There are interpreters who insist on finding simplicity in just those matters where complexity is both great and salient. It is my feeling that reverence for the text obliges a respectful interest in its origins, and respect too for all its origins seem to imply about the kind of interpretation the text permits, as well as the kind it seems to preclude. I would say, for example, that the work of the group called the Jesus Seminar proceeded on assumptions that grossly simplify these questions and, in effect, impugn the authenticity of the text, as many writers have done over the last few centuries. Some humility would be appropriate—there are those who earnestly believe that To Kill a Mockingbird was written by Truman Capote. The limits to what can be certainly known about such things are narrow at best. I suppose most Christians assume that the creation over time of the Gospels and the New Testament as a whole was an event of at least as great moment as the giving of the Law to Moses, or the moving of the Prophets to voice their oracles. The literal “how” of these events we cannot know, but we have the Law, and we have the poetry. If some intervening rabbinical hand strengthened or polished either of them, this may only have brought it closer to its true and original meaning. I am assuming here that Providence might be active in such matters.

To return again to what has been called “the sword of the Lord”: that phrase is itself an interpretation, since nothing in Jesus’s words suggests that the sword should properly be called his. The note in the always useful 1560 edition of the Geneva Bible says of the divisions among families and households that are the effect of this sword, “Which thing cometh not of the propertie of Christ, but proceedeth of the malice of men, who loveth not the light, but darkness, and are offended with the word of salvation.” This same phrase does appear in Judges, where the sword is wielded by Gideon. The book of Judges is a somber and impressively clear-eyed account of the crimes and catastrophes that beset primitive Israel. If Gideon avenges his brothers in his rout of the Midianites, in doing this he also acquires power so coveted by his son Abimelech that he kills his seventy brothers in order to make himself Gideon’s successor. And the phrase appears in fierce old Jeremiah, where it occurs as a lament: “Ah, sword of the Lord! How long till you are quiet? Put yourself into your scabbard, rest and be still!” (Jeremiah 47:6). The sword seems to have been wielded in this case by Nebuchadnezzar, who was attacking the Philistines. So this context does not support the idea that here violence is undertaken in the cause of righteousness by persons with any positive interest in the God of Israel. The prophet sees this disaster, like any other, as a judgment of the Lord, not as an endorsement of those who are his instruments in exacting it.

When he spoke these words, Jesus might well have foreseen that in bringing a new understanding of a traditional faith he would divide families—the “sword” he speaks of is the setting of fathers against sons and mothers against daughters. This is both inevitable and regrettable. In the narrative as I understand it, his words would be heavy with sorrow.

I have spent time over this phrase because it has been important in the history of Christendom and because I think it is important yet, an opinion I had arrived at before I looked it up on the Internet. Even among those Christians who are not so wedded to what some call literalism that they refuse to consider context, there is still an old habit of conflict within the house hold of Christ, the family of Christ, that flies in the face of that last...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherPicador

- Publication date2013

- ISBN 10 1250024056

- ISBN 13 9781250024053

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages224

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.25

From Canada to U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

When I Was a Child I Read Books: Essays

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Paperback. Publisher overstock, may contain remainder mark on edge. Seller Inventory # 9781250024053B

When I Was a Child I Read Books: Essays by Robinson, Marilynne [Paperback ]

Book Description Soft Cover. Condition: new. Seller Inventory # 9781250024053

When I Was a Child I Read Books Format: Paperback

Book Description Condition: New. Brand New. Seller Inventory # 9781250024053

When I Was a Child I Read Books

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 19007533-n

When I Was a Child I Read Books: Essays

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. Seller Inventory # 1250024056-2-1

When I Was a Child I Read Books: Essays

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Seller Inventory # 353-1250024056-new

When I Was a Child I Read Books (Paperback)

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Paperback. A New York Times Book Review Editors' ChoiceA New York Times BestsellerA New York Magazine Best Book of the YearAn Economist Best Book of the Year Pulitzer Prize-Winning Author of Gilead Marilynne Robinson has built a sterling reputation as a writer of sharp, subtly moving prose, not only as a major American novelist, but also as a rigorous thinker and incisive essayist. In When I Was a Child I Read Books she returns to and expands upon the themes which have preoccupied her work with renewed vigor. In Austerity as Ideology, she tackles the global debt crisis, and the charged political and social political climate in this country that makes finding a solution to our financial troubles so challenging. In Open Thy Hand Wide she searches out the deeply embedded role of generosity in Christian faith. And in When I Was a Child, one of her most personal essays to date, an account of her childhood in Idaho becomes an exploration of individualism and the myth of the American West. Clear-eyed and forceful as ever, Robinson demonstrates once again why she is regarded as one of our essential writers. In this new collection of incisive essays, Robinson returns to the themes which have preoccupied her work: the role of faith in modern life, the inadequacy of fact, the contradictions inherent in human nature. Shipping may be from multiple locations in the US or from the UK, depending on stock availability. Seller Inventory # 9781250024053

When I Was a Child I Read Books: Essays

Book Description Paper Back. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 104338

When I Was a Child I Read Books: Essays

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_1250024056

When I Was a Child I Read Books: Essays

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon1250024056