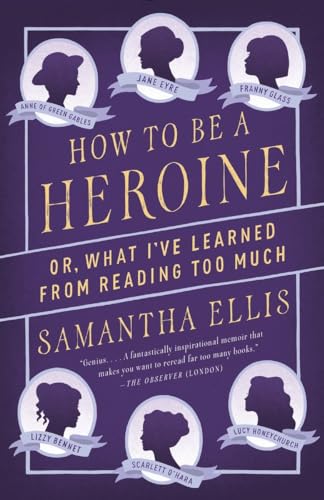

How to Be a Heroine: Or, What I've Learned from Reading too Much - Softcover

With this discovery, she embarks on a retrospective look at the literary ladies—the characters and the writers—whom she has loved since childhood. From early obsessions with the March sisters to her later idolization of Sylvia Plath, Ellis evaluates how her heroines stack up today. And, just as she excavates the stories of her favorite characters, Ellis also shares a frank, often humorous account of her own life growing up in a tight-knit Iraqi Jewish community in London. Here a life-long reader explores how heroines shape all our lives.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

1

THE LITTLE MERMAID

The summer I was four, I got lost on a beach in Italy. I wandered off from my family, and we didn’t find each other again for two whole hours. My mother says it was the worst two hours of her life. They had police helicopters out looking for me and everything. But although I knew I was lost, I wasn’t scared. It was my first time ever on my own. I walked further than I had ever walked. I made sandcastles with a small Italian boy. I went on past the tourist part of the beach, and it was just me and the sand and the sea and the sky. Walking along the very edge of the sea, splashing through the cool water, I felt amazingly free. When I was reunited with my parents, I cried. I was glad to be safe again. But it had been an adventure. And now it was a story, with me at the centre of it. And even then, I wanted to live a storybook life.

My young, beautiful mother had already had a storybook life, with a childhood in Baghdad, then persecution, a failed escape across the mountains of Kurdistan, twenty days in prison, a successful escape to London and a whirlwind romance with my father – all by the time she was 22. She was my first heroine. I thought her life was high romance. My mother did not. She wanted to shield me from suffering, she wanted me never to haveto go through what she’d gone through; she wanted me to have a boring life. Throughout my childhood, this outraged me. Never to have adventures? Never to do extraordinary things? Never to take risks? When I once wished aloud that I could go to prison because at least it would be interesting, my mother shuddered.

She wanted my life to have a happy ending: a wedding. Which I thought would be fine, if I could marry a prince. My first fictional heroine, even before I could read, was Sleeping Beauty. I liked her because she was beautiful. I wanted, very much, to have golden hair and blue eyes. My eyes had started blue and gone green, but maybe if I wished hard enough, they’d change back, and maybe my unruly brown curls would straighten and go blonde. Then I’d look like a princess, which was halfway to being one.

It was the end of the Seventies, and Lynda Carter was always on TV, as Wonder Woman, doing her dazzling spinning transformations. I would make myself dizzy in the living room, copying her, hoping my hair would fly free and a mystical ball of light would appear as my clothes were replaced, not by superheroine spangles but maybe by a dancing dress and probably a tiara.

And even though I now regard Sleeping Beauty with the proper feminist horror (her main characteristic is beauty! She spends a hundred years in a coma! She never does anything! She never wants anything!), I can’t help but feel a residual affection for her. Because she was my first fictional heroine and she gave me a desire, an aim, a goal: I wouldn’t have a boring life because although I would get married like my family wanted me to, I would marry a prince.

In the 1959 Disney film I watched over and over, the love story is the point. Sleeping Beauty is barely in danger. She’s not even asleep for very long. She meets her square-jawed prince before she pricks her finger, so the minute she falls asleep, the race is on to find her, kiss her (because only true love’s kiss will break the spell) and marry her. It all happens very quickly, and there’s a similarly swift resolution of the fairies’ argument about what colour Sleeping Beauty’s dress should be (obviously, it ends up pink). This all made sense to me, then. And when, a bit later, I read the story in Grimms’ Fairy Tales, where Sleeping Beauty is asleep for years and years, and the whole palace falls asleep with her, and a forest grows

up around them, and it takes a real hero of a prince to hack his way through, I liked that even better.

Now I find the Grimm story a bit prissy. I like the girl stopped in time and the freeze-framed palace servants, and the brilliantly disquieting image of the many sad, young princes who try to get through the forest but die, in the flower of their youth, because ‘the thorns held fast together, as if they had hands, and the youths were caught in them, could not get loose again, and died a miserable death’. But the story still hurtles towards a kiss, a wedding and a happy ever after. The version Charles Perrault wrote in 1697, a century before the Brothers Grimm cleaned up the story, is much darker and stranger.

Perrault’s story doesn’t end with the prince waking Sleeping Beauty with a kiss. Not at all. Instead, he goes on to tell us what happens after Sleeping Beauty gets married. She’s out of the frying pan and almost literally into the fire, because her mother-in-law is a jealous ogress who orders her steward to kill and cook Beauty’s children, Dawn and Day, in ‘piquant sauce’. The kind steward fools the ogress by cooking a lamb and a kid, but when she asks for beauty to be cooked in the same sauce, he panics, because although Beauty is officially 20, she’s been asleep a hundred years. ‘Her skin, though white and beautiful, had become a little tough, and what animal could he possibly find that would correspond to her?’ He decides on venison. But the ogress knows she’s been fooled, so she decides to kill Beauty, Dawn and Day herself. She gets a vat and fills it with vipers. Luckily her son returns and catches her red-handed. She dives into the vat herself and is devoured by the hideous crea- tures inside.

Only then can Sleeping Beauty and her prince and their mawkishly named children get a shot at living happily ever after. I love the fact that Perrault’s princess goes on living and struggling after she finds her prince, and that Perrault doesn’t shrink from the weirdness of Sleeping Beauty being over a hundred years old but having the body of a lithe young thing. When the prince wakes her, he considers telling her she’s wearing the kind of clothes his grandmother used to wear, but decides it’s best not to mention it just yet. Oh, and Perrault doesn’t specify that Beauty’s hair is blonde or straight. She could well be a curly-haired brunette.

Only recently I came across Giambattista Basile’s even earlier version of the story, from 1634. His princess, named Talia, is warned that she will be in mortal danger if she ever goes near any flax. Her father duly forbids all flax, but one day Talia sees an old woman spinning, pricks her finger and falls down dead. The old woman is so scared that she runs away and, says Basile, ‘is still running now’. Talia’s grieving father has her laid out in one of his country mansions. Some time later, she is raped by a passing king and, nine months later, still unconscious, she gives birth to twins. Trying to find milk, the babies mistake her fingers for nipples and suck out the flax. The princess awakes. The rapist king returns and everyone’s delighted. The only problem is, he’s already married. So he takes Talia and her children to his palace and hides them away. His wife, understandably put out, tries to kill, cook and eat the inter- lopers. At the last minute she’s foiled, Talia becomes the new queen, and the rather queasy moral of the story is that lucky people find good luck even in their sleep.

If I’d read that version as a child, then – like the old woman – I’d still be running now. But now even this nasty tale seems preferable to the mindlessly syrupy Disney film, with its faux- medieval costumes, simpering wasp-waisted princess and long scenes where she charms the forest creatures by trilling the same song over and over. I can’t fathom why I ever wanted to be her. Though I still kind-of sort-of want her hair.

I do try to fight this retro-sexist yearning, but a few years ago, already in my thirties, I was interviewing an Orthodox Jewish wig-maker, as research for a play I was writing, and she invited me to try on a wig. I hesitated. She told me to shut my eyes. She pulled my hair taut into a bun at the nape of my neck, covered it in a net and scraped the wig’s combs in at the sides to secure it. When I opened my eyes, I couldn’t believe it. In the mirror there I was with fairy princess hair – blonde, poker-straight, shimmering to my waist. ‘Does it move?’ I whispered. She smiled. ‘Why don’t you flick it?’ I did, and there I was, like the girl in the meadow in the Timotei advert, with my very own cascade of golden hair. Clearly, I hadn’t entirely grown out of Sleeping Beauty.

Last year, as I watched Disney’s recent film Tangled, I longed to have hair like Rapunzel’s, not just blonde but so long she can use it to tie a man up, let herself down from a tower, and as a zip wire, lasso and swing. Rapunzel’s hair even has magic healing powers. When it is cut and changes to a lovely burnished chestnut brown, she finds out that her tears can heal as well as her hair ever did; because, it turns out, brunettes are magic too. (Also in Tangled, when they kiss at the end, she dips him. Revolutionary stuff!)

Then, though, my hair wasn’t the only thing stopping me becoming a princess. There was a bigger obstacle. I loved sitting on the edge of my mother’s dressing table, watching her put on her make-up, and playing with the kohl pots she’d brought from Baghdad, two shaped like trees, one shaped like a peacock, with a tail you pressed down to release the stopper. One evening, I confided my life plan, but she said, ‘You can’t marry a prince.’ Just like that. ‘There are no Jewish princes.’ I was crestfallen. It did not occur to me that I didn’t have to marry a Jew, or marry at all. I thought my dream was over. How would I ever become a princess now?

This conversation was the beginning of my realising we were different. My mother would say ‘We are Jews. We never know when they might not like us any more and we’ll have to get on a boat and just get out.’ We had to stick together, we had to be alert, we had to avoid non-Jewish princes. And as Iraqi Jews, we were different even from other Jews. We ate rice instead of gefilte fish, we belly-danced instead of watching Woody Allen. We were a tiny community, a self-contained little world. So rarely did I meet anyone who wasn’t an Iraqi Jew that until I went to school, I thought all grown-ups spoke Judeo-Arabic, and that English was just a children’s language. I assumed that when I grew up I’d be fluent in Judeo-Arabic, just as I’d be taller. And married. And allowed to drive.

At the weekends, my family would sit around a table at my grandparents’ house in Wembley, chain-smoking and talking about Baghdad. Their stories emerged from a grey-blue cloud. One of my earliest memories is of sitting under the table, pulling the stalks off parsley to make tabbouleh while above my head, the women made sambousek bi tawa (pastry crescents filled with spiced chickpeas), or purdah pilau (chicken and rice cooked in a ‘veil’ of pastry), or ras asfoor b’shwander (literally, little birds’, heads, actually small meatballs cooked with beetroot in a sweet and sour sauce). Iraqi Jewish food is all mixed up, sweet and sour together, and so were the stories.

They talked about sleeping on the roof in the hot summers and seeing shooting stars, which they thought were UFOs; about the gazelle they kept as a pet; about learning to swim in the Tigris; about eating water buffalo cream for breakfast, sold by women who carried it on their heads in round, flat trays. It was as thick as cake, and the women would slice it with a hairpin for them to take home and eat with warm pitta bread and black, sticky date syrup.

They had ice cream that was chewy because it was made with mastic from crushed orchid roots – I’ve tasted it in a Turkish café in London so I know it exists. But I’ve never eaten masgouf, the enormous flat fish hauled from the Tigris and roasted on the riverbank, with spices, over an open flame. I’ve never seen the sandstorms that turned the skies red or the blind master musicians in dark glasses playing languorous songs of lost love.

I desperately wanted to go to Baghdad, preferably by magic carpet. I’d watched The Thief of Bagdad and Sinbad the Sailor, and I had a very clear image of my grandmother setting off for the copper market (where the banging was so loud you had to communicate in signs) perched elegantly on a fringed rug. But the red-and-blue carpet in our house wouldn’t fly, no matter how long I spent sitting on it and wishing.

It was at synagogue, at Purim, that I found a possible solution to my princess problem. A loophole. The festival of Purim celebrates a heroine, Esther, who is Jewish and a queen – which was almost as good as being a princess. Like all small girls, I was less interested in queens than in princesses. Usually once a fairytale princess has married her prince, there’s nothing more for her to do and the story is over. But Esther’s story goes on after her marriage to King Ahasuerus as she saves the Jews of Persia from the prime minister who wants to kill them all.

At Purim, when we read the story, we would shout, stamp and rattle noisemakers to drown out the baddies’ names. Grown-ups were required to drink so much they forgot the difference between good and evil. Iraqi Jews gamble at Purim, so my synagogue would hire baize tables and roulette wheels to become, thrillingly, for just one night, a makeshift mini Monte Carlo. But the best thing about Purim was that it was the festival of fancy dress. All the girls wanted to go as Esther. In Tel Aviv, the whole city celebrates with a boozy, three-day carnival, and in the Orthodox suburbs hundreds of girls dress as Esther, all in white, with sparkly tiaras and wispy veils and bouquets of orange blossom; endless tiny brides. My Esther dress, made by my mother, was cream satin with gold braid and a tiara of silk roses. She zipped me into it and even daubed my eyelids with her best Seventies disco blue. I wanted to be Esther every day of the year.

My Hebrew teachers said I should like Esther for saving the Jews, but I was more interested in the bit before that, where she gets her king by winning a beauty contest. I imagined her as pretty as Sleeping Beauty, but a brunette. With green eyes. All right, I imagined her as a gorgeous, grown-up version of myself. And she was Jewish, and she did become a queen. (At Hebrew school, we skated over the fact that she married a man who wasn’t Jewish. Everything was forgivable in a heroine who saved the Jews.)

Later, in synagogue again as a bored teenager, refusing to dress up and irritated by the noisemakers, I actually read the Megillah myself and I was shocked. There is no beauty contest. Ahasuerus is no doe-eyed prince. He’s already executed his first wife, the captivating Vashti, for the monstrous crime of refusing to come when he sends for her. Esther attracts his attention when her uncle gets her to join the sex-starved king’s harem.

Once queen, she does save the Jews. But she does it so passively. When she hears that the prime minister plans to kill her people, she’s too timorous even to go and see the king. Instead she starts fasting. It doesn’t say why. Does she fast for luck? Does she fast because thin girls win? No one knows. After three days, she invites Ahasuerus to d...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherVintage

- Publication date2015

- ISBN 10 1101872098

- ISBN 13 9781101872093

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages272

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 3.99

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

How to Be a Heroine: Or, What Ive Learned from Reading too Much

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 4JSXJ6000IND

How to Be a Heroine: Or, What I've Learned from Reading too Much by Ellis, Samantha [Paperback ]

Book Description Soft Cover. Condition: new. Seller Inventory # 9781101872093

How to Be a Heroine: Or, What I've Learned from Reading Too Much

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. unused book from closed bookstore inventory; clean, tight and square, no spine crease, no tears or other creases, text is clean and unmarked. Seller Inventory # 500364

How to Be a Heroine Format: Paperback

Book Description Condition: New. Brand New. Seller Inventory # 9781101872093

How to Be a Heroine: Or, What I've Learned from Reading too Much

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # ABLIING23Mar2317530259121

How to Be a Heroine (Paperback)

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Paperback. While debating literatures greatest heroines with her best friend, thirtysomething playwright Samantha Ellis has a revelationher whole life, she's been trying to be Cathy Earnshaw of Wuthering Heights when she should have been trying to be Jane Eyre. With this discovery, she embarks on a retrospective look at the literary ladiesthe characters and the writerswhom she has loved since childhood. From early obsessions with the March sisters to her later idolization of Sylvia Plath, Ellis evaluates how her heroines stack up today. And, just as she excavates the stories of her favorite characters, Ellis also shares a frank, often humorous account of her own life growing up in a tight-knit Iraqi Jewish community in London. Here a life-long reader explores how heroines shape all our lives. "A Vintage Books original"--Title page verso. Shipping may be from multiple locations in the US or from the UK, depending on stock availability. Seller Inventory # 9781101872093

How to Be a Heroine: Or, What Ive Learned from Reading too Much

Book Description Condition: New. . Seller Inventory # 52GZZZ00M2FZ_ns

How to Be a Heroine: Or, What I've Learned from Reading too Much (Vintage Original)

Book Description Condition: New. 272. Seller Inventory # 26372316154

How To Be a Heroine or, What I've Learned from Reading Too Much

Book Description Trade Paperback. Condition: New. No Jacket. New Book. Seller Inventory # 307593

How to Be a Heroine: Or, What I've Learned from Reading too Much

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Original. Special order direct from the distributor. Seller Inventory # ING9781101872093