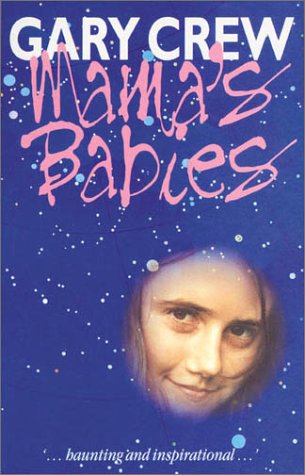

Mama's Babies - Softcover

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Chapter 1: A Parcel Changes Hands

By the time I was nine years old I had begun to doubt that Mama Pratchett, the woman with whom I had lived for as long as I could remember, was in fact my mother. My doubts were based upon a growing understanding that no woman, not even Mama Pratchett, could possibly have given birth to five further children aged at that time between one year and five, especially since none were twins. Yet there we were, living under one roof, all six of us calling her "Mama."

With so many little ones about, it also seemed strange that there was no "Papa Pratchett," and question Mama as I might, I was unable to establish that there ever had been.

There were more sinister reasons for my doubts. While all of Mama's children, from babes in arms to toddlers, seemed simply to appear, there were others who disappeared just as suddenly, often before I had even learned their names.

It was sudden appearances and disappearances, more than any other circumstance, that led me, at last, to suspect Mama Pratchett. And to observe her ways.

"Sarah," Mama said to me one morning, "I want you to come down to the station with me. Leave the children. We won't be long."

That Mama was going "down to the station" was not at all unusual. In fact, railways in general seemed to be a part of her reason for being. No matter how often we shifted house (which was very often, and for no good reason that I could detect), our new abode was always beside the line, often a former railway worker's shack, now cheaply rented, or once, when we were very lucky, a little stone cottage that had been the station master's. But the strange thing about Mama's going this morning was that I had been invited, a circumstance which had never occurred before. For this reason alone I was eager to oblige.

"When?" I asked, giving a firm wring to the diapers I was washing.

"I'm due to meet the ten-fifteen from Peachester," she said. "I have a parcel to collect. I mustn't be late."

"A parcel?" I queried. "If it's only a bundle of sewing, couldn't it be left with the station master? I could collect it when I have finished here."

Mama made what little money came into our house by working at home as a seamstress. It was quite common for her customers to send her bundles of clothes by rail. But in this case it seemed that my assumption was wrong.

"No," she declared in a tone that would brook no argument, so I left the diapers to soak, pulled on my bonnet, and waited dutifully by the gate with a swarm of little ones hanging on my skirt and begging to come with me.

Mama appeared soon after, decked out in her best to meet the train. Perched upon her steely gray hair, which she parted in the center and pulled back into a bun, she wore a pillbox hat of black satin, tied beneath her many chins with a most audacious bow. Mama was a naturally imposing woman, big-boned and heavy-set, but when these physical attributes were accentuated by her particular choice of clothing, especially severely cut skirts and jackets (usually of battleship gray), her black stockings, walking shoes, and an enormous black leather handbag, she was truly a force to be reckoned with.

"Hurry up," she called as she reached the gate, and when I had disengaged myself from the children, I followed hastily, feeling a little like a dinghy dragged in the wake of a mighty vessel.

To be addressed gruffly was not new to me. Being the eldest of the children and the one who had been with Mama the longest, it had fallen to my lot to be treated more as a maid than as a daughter -- except that a servant would have been paid and a daughter would have been loved. I had never been fortunate enough to receive either love or money. In those days I believed that this lack of attention or affection was due to my being plain. It is true that I was pale and thin, my face pinched, my eyes gray, and my hair mousy and lank. Nor did I have a vivacious or winning personality. Still, since it was pointed out to me daily that I was lucky to have a roof over my head and food in my stomach, I did not complain.

So I hurried along behind Mama, thankful for the opportunity of breaking the monotony of my day and excited at the thought of seeing Mama's mysterious parcel, particularly as it was too important -- or possibly too precious -- to leave in the care of the station master.

At that time we were living on the outskirts of a village called Waterford. It was a miserable place. Once, they said, it had thrived on the extraction of peat from the swampy, wind-driven wasteland that surrounded it, but when the peat proved to be of too poor a quality to extract, the industry had failed and the population moved away. Now the village was almost deserted. One or two old folk remained, including the grocer, Mr. Dibbs, who sold little more than moldy potatoes. And there was the railway station, manned solely by the station master, Mr. Quaver. He was aptly named considering that, through either age or some terrible affliction, he spoke in a curious high-pitched tremolo, rendering most of what he said -- which was not much, since he was a solitary individual -- very difficult to understand.

Yet everything about Waterford was not as gloomy as the picture that I have painted. There was one salvation. This was the nephew of the wretched Mr. Quaver, a boy called Will who would often take the train from Ipswich, where he lived and went to school, to spend the weekend with his lonely uncle or, more correctly, to wander among the reedy pools and dense thickets of the swamp in search of adventure.

I first met Will Quaver when he passed our shack one day. Hearing my charges squealing in the front yard, I left my sweeping and went to the door to look. In the middle of the road was a gangly red-headed boy, perhaps a year or two older than myself, entertaining the children by performing cartwheels and handstands. I saw the boy as no more than a show-off and would have shooed him away with my broom if he had not caught sight of me and ceased his display immediately.

"Hello there," he said. "I'm Will Quaver. My Uncle Bertie's the station master." His manner was so pleasant that I could even forgive him his shock of hair, which appeared to have been struck by lightning. "Are all of these kids your brothers and sisters?"

As amiable as he seemed, the boy was still a stranger and, as such, a threat that Mama would never tolerate -- particularly a stranger who asked questions about her children. Once, when I had plucked up the courage to ask her why other children couldn't visit, she turned upon me and said, "What? Aren't there enough already?" Which was true, I suppose.

And so, when Will Quaver asked about the children, reasonable as his question was, I replied, "That is none of your business. Now be off with you," adding, as Mama would have done, "Children, come inside this minute." The pity was that I was not Mama, and neither the boy nor the children moved. "Do you hear me?" I bawled again, at which Will Quaver laughed.

"Well, well," he said, "it seems that you have no control over your little family. And you have none over me either, since I am on a public road."

At this I turned on my heel to fetch Mama, but by the time she had reached the door, the boy was gone, though the children still hung over the gate, calling after him as he skipped cheekily down the road.

That was my first meeting with Will, and in the three or four that followed, little advance was made, except that his persistence became more evident and my amusement at his antics and devil-may-care boldness increased. Finally, on a day when Mama had gone to the Saturday market in a neighboring town, I discovered Will in our front yard playing leapfrog with the children, and from that day on,

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherLothian

- Publication date1998

- ISBN 10 0850918278

- ISBN 13 9780850918274

- BindingPaperback

- Edition number1

- Rating

(No Available Copies)

Search Books: Create a WantIf you know the book but cannot find it on AbeBooks, we can automatically search for it on your behalf as new inventory is added. If it is added to AbeBooks by one of our member booksellers, we will notify you!

Create a Want