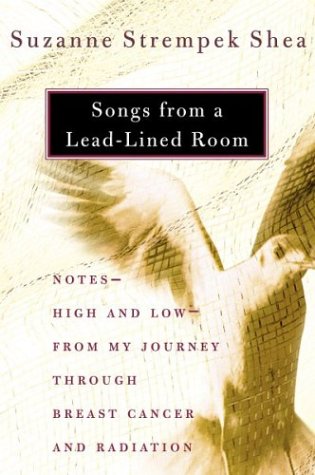

Songs from a Lead-Lined Room: Notes-High and Low-From My Journey Through Breast Cancer and Radiation - Hardcover

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

my new guru has an office on the deep-down floor of the big hospital.

The walls here are yards thick and they are lined fat with lead.

There is bad stuff being dealt with here, and it needs to be contained—not

just the danger that people who come here are carrying inside themselves,

but also the things that are aimed at them down here to try to kill that

danger. Everything here is bad. Even the radio reception. Only one station

can be caught through the fortress walls and it"s lousy. Lion King. Disco

revival.

The guru"s room is the size of a car. A budget rental. Two chairs,

and a shelf for a desk. Today she has offered me the option of having our

session observed by an intern. This hospital is a teaching place, so at least

one student in on an appointment or exam or procedure is not uncommon.

Since late winter, in the name of education, dozens of strange hands have

been placed on one of my more private areas. I"d get probed, and then

thanked, and then later they"d see me in the hall with my clothes on and they

wouldn"t even nod a greeting. Kind of like high school. The weird thing about

today is that it seems odder to have a stranger in on the listening than the

touching. But I don"t mind. I feel bad in my soul and at this point might even

say yes to a live telecast.

The intern"s name is Holly. It"s bright, and, of course, holidayish.

Holly wants to become a nurse and is attending Springfield College, so I

compliment her because that is a fine school. She smiles from a face that

belongs on a good-looking religious statue. Clear and open and ready for your

prayers, and I wonder, in years to come will she turn out to be the kind of

nurse who held my hand an hour past the end of her shift even though she

really needed to get to the grocery before it closed. Or will she get burned-out

and hateful like the one who shouted at me the time I asked again for a

painkiller. You can"t tell these things in advance, about how Holly, or

anybody, might act in time. But for now, she shows every sign of being the

type of nurse you"d want: interested, leaning in, but not getting in the way of

my guru, Wendy, who knows what to say and when to shut up.

Wendy has not had this. I know because I asked, the first time I

met with her as part of the package deal of radiation. If we have the

inclination and time, we patients down here can be connected to helpful

resources and activities that include a chaplain, massage therapists, reiki

practitioners, meditation sessions, writing groups and art workshops. Colorful

posters and leaflets hang in the waiting rooms and locker rooms, announcing

the next series of courses. I was more in the mood to complain about my

problems than to weave potholders. So I leaped at the chance for

psychotherapy, and in Wendy found one of those huge iron posts to which

they moor freighters at a dock. I was bobbing around, she was a possible line

to stability. I connected with her right off, and right off I asked her: "Did you

ever have this?" Knowing that was important to me. A lot of such things

were—and are—important: and, top of the list, am I going to die from this? I"d

asked that one three months earlier, of the nurse, on the phone the night I

received my diagnosis. Cindy later said, "Wow, you asked that? I never

thought to ask that." My bestfriend never thought to ask; even though her

diagnosis eight years before had been dire. For me, despite the blessing of

early detection and a classification of Stage One out of four, it was the first

thing I wanted to know. You hear the word "cancer" and your name in the

same sentence, and you can already see your name carved into the stone.

At least I could.

So I needed to know if Wendy had personal knowledge of what

she counseled people about while she sat all day in her tiny office on the

deep-down floor of the hospital, doing her social work. She told me no, she"d

never had it, but she went on to tell me she had known some of the forms of

hardship that befall anyone who"s alive, and I was all prepared to hear her go

on and tell me about her cesarean, thinking she might be another of the

surprising number of women who, when they learn about what"s happened to

me, scramble for a story to swap and start reciting, "Well, I went through fifty

hours of labor only to have a cesarean." They got a child for all their misery, a

bit more positive an experience than having mortality in your face, which is

how the guru put it the first time we met. In your face. That"s where it is with

cancer. Of the fingernail, or of the brain. That"s the thing. And even though

Wendy has not had this, or any cesarean that she cared to mention, I felt

she knew what she was talking about, and that she would help.

So I regularly will be going to see her in her office on the deep-

down floor, where the waiting room is packed with people wondering what do

you have and how bad is it? I should note, that is what I am wondering:

what"s he got? And what about her? A couple is sitting together, and you try

to guess which one of them is the patient. Most of the people I see there are

older. Some look terrible. But some look pretty good, and you have to remark

about that, if only to yourself. One elderly man was showing off a diploma

today. They actually give you a diploma when your treatments are over,

which I think is a ridiculous thing. But this man apparently didn"t. He

appeared to be very proud. And, I have to say, he looked great. He didn"t look

sick. But then, I don"t look sick. I don"t feel sick. Yet I"m to be coming here

five days a week for the next six and a half weeks, to get myself radiated

while the theme from The Lion King plays and the technicians answer my

fears by saying no, don"t worry, this is not a dangerous thing being done to

you here, and then they file from the room and shut the door and a red

warning light beams from the ceiling so nobody will come back in until it"s

safe again.

This machine on which I am to be radiated is so old the

technicians admit they don"t even know its age. It is the dull tan color of the

IBM Selectrics I used in the newsroom when I first worked as a reporter. Like

the Selectrics, it is worn and scratched. But unlike a typewriter, it takes up

an entire end of a room and has a moving arc-shaped part that curves around

your body to the sound of a compressor, and if you were claustrophobic you

might have trouble here. There is a new high-tech machine at the other end of

the hall and there is to be an open house next week to show it off to the

public. I have been given a laser-printed invitation to this event, which will

include refreshments, and I ask if this means I will be treated on the newer

model. No, I"m told, it is for dealing with parts found only in men. The cobalt

machine—mine—does what"s needed for me, I"m assured, has done the job

for women for who knows how many years, and certainly will for my six and a

half weeks. Maybe so, but to look at my machine, you"d think the power

source was a crank and a pair of hamsters on a treadmill. Somebody has

stuck pictures onto the part that encircles you. Transfers, the kind that

people once dipped in water and applied to their kitchen walls. Two cardinal

birds, both boldly red males, sit on a pine branch. A big pink flower blossoms

nearby. These are supposed to cheer you, I guess. They don"t work.

I feel rotten, I tell Wendy afterward, back in her little office with

Holly in a chair she"s jammed into the corner behind the door. I am worn out

and defeated and I don"t want to be coming to this hospital or anywhere near

this hospital and I"m not happy that it"s going to take no less than three

weeks for the country"s number-one antidepressant to kick in and give me a

leg up and over the wall. I don"t want to have cancer. I don"t like having

cancer. I turn to Holly even though the deal is I"m supposed to be pretending

she isn"t there. I tell her this has been going on for way too long, in my

opinion. Since March. Fucking March. And here it is, September. Annual

mammogram at the tail end of winter—what"s this here? Another appointment

to find out—no, that was nothing after all. But can you come back so we can

take a look at the other breast?

I"m forty-one and in the best physical shape of my life. Or so I thought. Go

down the waiting room–posted list of preventative measures, and I"ve met

them all. Because I thought my parents would kill me, I never once smoked.

Or inhaled. Anything. Because I love being outdoors, I walk daily, in all

weather. Because I woke up to the cruelty involved, I stopped eating meat

more than a decade ago. Because it doesn"t take much, I don"t drink much. I

was happy without having to force it. If this counts for anything, I went to

church, I gave to charities, I packed groceries at the local food pantry, I

recycled, I captured and released any bugs found in the house. I even bought

the postal service"s special breast cancer postage stamps, despite their

costing seven cents more than the regular kind. Nothing"s perfect, but I was

in a life that always had made me feel lottery-lucky. I didn"t squander that—I

took care. I have no family history of the disease, but since age thirty-three

faithfully have been going for mammograms due to a benign cyst discovered

the same exact month Cindy was diagnosed. And about which, due to my

guilt over escaping away free that time, I did not tell her until this year. Until

my own bad news. Eight years back, though, from the unscathed side of our

parallel universes, I watched her fight for her life. And I guess I have never

stopped fearing for my own.

So at end of this past winter, I went for my usual look-see and

was asked to return. And to come back again. There were more

examinations for me. More mammograms in a single day than there are m"s

in the word. An ultrasound in May. An extremely uncomfortable three-hour

stereotactic core biopsy in June, my left breast dangling through a hole in a

raised table while, seated below like a car mechanic working on a rattling

muffler, a radiologist drilled repeatedly for samples.

Then it"s the Fourth of July and we are visited by this blowhard

guy and his wife and his two little kids, all of them out from Ohio. They lived

here long ago, they knew my husband Tommy then, they always had meant

to visit on trips back. And finally here they are in my home and I don"t know

any of them and I don"t want to know any of them and I don"t want them to be

there and the night is dragging and the wife is nice enough but the guy won"t

shut up about downloading music from the Internet and when I finally find

something to insert into the conversation, the name of an album I"d been

listening to recently, he says, "Oh, you just heard of them?" The "just" is big,

the size of a movie screen on which can be shown a film of my general lack

of knowledge of what is hip. The kids don"t care who knows what. They are

restless and want to run in the rain that is pouring and when their parents say

they cannot, they shout how they hate them and even though I don"t know

them I hate them, too, and I"m just begging them in my head to get out my

house and leave me alone because tomorrow I"ll be told what I"ve got or not

got, growing in what the clinic"s paperwork maps out as the upper left

quadrant of my left breast.

The family eventually leaves, of course, and the next day arrives,

of course. And, of course, the call does not come anywhere as swiftly as I

would like. I"m waiting all the day and on the hour I"m pestering the nurse on

the line, she says the doctor"s in surgery and I"m thinking how it"s an awful

long operation already, taking this many hours—somebody must have

something really bad that needs repair. I pray for whoever it is. I"ve always

liked to pray for strangers. They"ll never know. It"s as if you"re sending

something out there, invisible, unexpected, the source unknown if the

beneficiary ever did stop to wonder why things maybe ended up the way they

were hoping. Powerful stuff it can be. But I don"t pray for myself on this day.

And I haven"t since, even though I have spent much of my life begging daily

for favors, most of them for me me me. The instinct to do that has vanished.

Lots of things have fallen away in these months and don"t seem to matter,

and I wonder if they ever will.

I have a basket of get-well cards, the wicker almost dissolving

from the sweetness of the messages. Everybody offers to take up the slack

of the praying for favors. I don"t even know some of these people. I am on

actual lists at local churches, my name typed under the heading of "sick" and

placed at the feet of the statues of saints known for their great batting

averages in interceding. I"ve not personally seen any of these lists, and I don"t

want to. I don"t look sick. I don"t feel sick. Why should my name be on a list

that says I am? I go to the CVS to pick up the country"s number-one

antidepressant and a stranger stops me to ask what"s wrong with me—her

whole entire church is praying for me and she wants to know: "What"s

wrong?" Other than "Who are you?"—which I do not reply—I don"t know what

to answer. I just shrug, "Oh, well, things. . . . " but I would like to add that

maybe the praying should have begun a little earlier. Like three months

before, on the fifth of July, when I was waiting for the doctor to phone me.

Tenth call to his office. Last few times, the nurse has been saying yes, yes,

she has the results now, but only the doctor can give them out. So I ask her

this: if it was good news, would I have to wait for the doctor to tell me? That

gets her thinking, and even though she prefaces how it is against the rules,

she reads me the results. I have Cindy"s medical book in front of me. I"m

looking up the words as the woman is giving them to me.

My fifty minutes are up. Holly will be able to do an entire term paper now. I

repeat to her face that I don"t want this—what"s happened so far in these six

months and what is to come. The prognosis is good, I realize things could be

much worse, but it"s happening to me. And that makes it bad enough. I slide

from feeling as if I"m whining to feeling justified about the whining, then back

again, sometimes with Olympian luge speed. I whoosh unprotected down the

icy incline of helplessness and unknowing, no sled beneath me, no snowsuit

padding, no clothing at all, no cap or mittens or boots, no nothing, no skin

even, it"s like my bones are showing, I feel so down to the base of whoever I

am, more naked than the moment I was conceived, feeling everything. Same

time, feeling nothing.

"I just don"t want this," is how I condense all that. And however

Holly views this, she doesn"t let on. Wendy does, though, and she

asks, "Well, what do you want?" which is a good question, both right then or

anytime.

I tell her this:

"I just want my life back the way it was."

My life.

I liked it.

I liked it the way it was.

I had it good, and was smart enough to realize that. To be grateful.

Well into adulthood, I still held the practice of evening prayers, still

moving through a trio I"ve said in my family"s native Polish, long ago having

hitche...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherBeacon Pr

- Publication date2002

- ISBN 10 080707246X

- ISBN 13 9780807072462

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages204

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Songs from a Lead-Lined Room: Notes-High and Low-From My Journey Through Breast Cancer and Radiation

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_080707246X

Songs from a Lead-Lined Room: Notes-High and Low-From My Journey Through Breast Cancer and Radiation

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think080707246X

Songs from a Lead-Lined Room: Notes-High and Low-From My Journey Through Breast Cancer and Radiation

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard080707246X

Songs from a Lead-Lined Room: Notes-High and Low-From My Journey Through Breast Cancer and Radiation

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks569021

Songs from a Lead-Lined Room: Notes-High and Low-From My Journey Through Breast Cancer and Radiation

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new080707246X

SONGS FROM A LEAD-LINED ROOM: NO

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.85. Seller Inventory # Q-080707246X