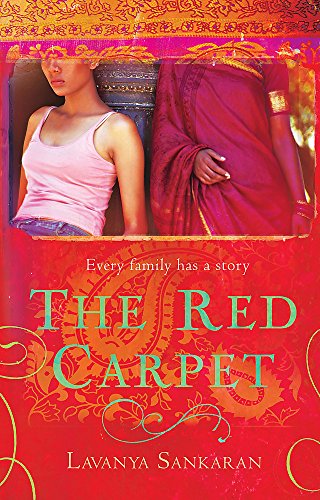

The Red Carpet - Softcover

Friction between the generations, always the stuff of great fiction, is nowhere stronger than in banglore, indias silicone valley, where software billionaires, beggars and the legacy of the raj combine and collidethe red carpet is an astonishingly enjoyable collection of stories as rich and absorbing as any novel from traditional mothers trying to marry off their westernised children and old-fashioned chauffeurs struggling with racy employers, lavanya sankarans tales of the clash between east and west are a pleasure and a revelation

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

Lavanya Sankaran's work has been published in the Atlantic Monthly and the Wall Street Journal. She attended Bryn Mawr College and has worked in investment banking in New York and consulting in India. She lives in Bangalore, where she is currently at work on her first novel.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

Bombay This

Ramu studied the animated woman in front of him, a slight smile on his lips. And apart from the minor variances: his gender, darker skin color, the carefully trimmed goatee resting on his chin, and the worrisome hairline that danced away from his forehead in the coy manner that plagued so many men in their early thirties, it was practically a Mona Lisa smile--full of mystery and hidden amusement.

The woman, Ashwini, was a recent import to the city, having moved to Bangalore with her parents after living her whole life in Bombay. After a year here, she was still going through withdrawal symptoms, and her conversation was frequently colored with Bombay this and Bombay that and in Bombay we and o god why can't Bangalore? If she were smart, he thought, she would learn that this invariably irritated her listeners, many of whom had lived in other parts of the country and indeed the world, but on the whole had managed to assimilate into this southern city with considerably more grace. One saw her everywhere however, in all the pubs and all the parties, because in addition to her list of nostalgic complaints, she was also armed with a lot of verve and fun. She was up for anything, a good-time charlie, a bustling ball of energy and laughter, a squeal and hug and kiss for everybody, her hips grinding inadvertently but pleasantly against the men she talked to as her bottom swayed happily to passing bits of music.

When she met people at parties, she didn't (as Ramu might) smile, chat, and withdraw from them until the next party. Instead she had the knack of making friends, and (before they knew it) of climbing deep into their lives. Then, there she'd be: visiting, cooing to their children, listening with concern to tales of their mothers-in-law, proffering advice on where to get the best blouse tailor versus the best pant tailor and who caters the best party souffles, all of which she amazingly seemed to know, pulled out of the air of a strange and new city by some inexplicable consumerist osmosis. Every party Ramu attended recently had some contribution by her: Ashwini did the decorations, the hostess would say. Ashwini brought the sweet. Do you like the curtains? Ashwini showed me where to buy them. And all this, of course, to Ashwini's tune of Bombay this and Bombay that.

As far as Ramu was concerned, she was just one of those women one met in the evenings and promptly forgot about in the mornings. It was only recently that his interest had taken a direct and more personal turn.

Now he studied her and realized how self-defeating her actions were. He felt a sudden urge to explain this to her (first, of course, sitting her down in a corner armchair, extinguishing her cigarette, placing her drink on a side table, and waiting for her eyes to focus on him instead of dancing about the room): Bangalore was a strange city, a potpourri of beggars and billionaires and determinedly laid-back ways. People dressed down here, not just on Fridays, but every day, and more so on occasions--and gently derided those who didn't. They spoke of their city's attractions to visitors in tones of disparaging surprise. Oh. You like the weather? Yeah, it's okay. I guess. Cool. Blue skies and all. Cosmopolitan people, you think? Yeah, they're a mixed bag. Different, one-tharah types. Not so hard-and-fast. A chill crowd, like. Doing ultra-cool things chumma, simply, for no reason other than to do it.

"See the software lads," he could say, by way of example. See the software lads shrug off their stock options. (No, no, I'm still a simple saaru-soru rasam-and-rice guy at heart.) See the software lads morph their inner Walter Mitty into Alfred Doolittle (I swear, da, it was just a little bit of blooming luck). See them stab each other in the back trying to prove that they too can please-kindly-adjust, the mantra that the city uses to exact merciless compromise from all of its denizens.

Such self-deprecation appeared modern, with its blue jeans and infotech ways, but was actually a very old courtesy. Deride yourself so others may praise you. Did Ashwini know this? Did she know she was spreading irritation before her like a virus? And here, Ramu found his thoughts slowing to a halt. Perhaps she wasn't. Perhaps no one else was really bothered by it. Actually, until recently, neither was he, previously just swatting her behavior out of his mind as he might a fly. At parties, after all, one met all sorts of people and thought nothing further of it.

Until recently.

"Oh god," Ashwini was saying, "you should just see them, yaar. Everybody does it, all the time. In parties, in bars, in people's houses. You're talking to somebody, and then suddenly, they're doing a line. It's crazy!"

The people listening to the excited pitch of her voice did so with an air of fascinated disapproval, like height-of-empire englishwomen being regaled with missionary tales of naughty hindoo heathens. Ashwini was just back from a trip north, and deeply impressed by the spread of cocaine in polite Bombay society. I mean, she said, you don't see anything like that here. In Bangalore. No indeed, thought her listeners primly, all of whom smoked the occasional joint, but nothing more. They were strictly old-fashioned in that way.

"Did you try any?" someone asked.

"Oh god, no! Even though my friends--from good families, you know, from big industrial families--even though they all kept asking me to do it, I said no. They kept saying: god, you're so cool, so hip, why don't you try it? I said, nothing doing, I'll drink all the vodka and smoke as many joints as you like," said Ashwini, proceeding to demonstrate, "but this, nothing doing! Shit yaar, imagine me doing cocaine!"

Shit, thought Ramu, imagine anyone giving a damn.

Three days later, Ramu left his mother's presence with a vague feeling of doom.

This was not going to work.

Entrusting such a crucial mission to his mother was becoming a farce: like sending someone to the market with strict instructions to buy luscious, juicy fruit, and having them repeatedly, idiotically, come home with boring, healthy-for-you vegetables.

Yet Ramu couldn't extricate himself easily. He was, like any unmonk, a captive of his desires.

In recent months, Ramu had found himself attracted, regrettably, not to the pretty young things he met all over the place (for apart from a fierce desire to shag them, there was nothing else he could imagine doing with them); rather, he found himself being drawn to the wives in his circle of friends. Women his own age, claimed by marriage and scarred by childbirth years before; women who waded comfortably between dirty diapers and smelly spouses and stressful jobs and thieving servants and occasional bright evenings filled with beer and good cheer. They laughed easily with him, without that brittle coquetry that younger, single women offered in the name of flirting. They sometimes shone with all the gloss of a recent visit to the beauty parlor, but were more frequently without makeup, displaying casually hirsute underarms and rough-stubbled legs dressed in old shorts. Yet he was seized with feverish desires to taste the beaded sweat on their upper lips as they frowned over some chore, and to bury his nose and mouth and body in the liquid warmth between their thighs. He wanted to make homes with them. He wanted to fill himself with their comfortable, lazy sexuality. He wanted to spend hours in their kitchens cooking vast and creative Sunday meals with them, and then spend hours more eating and drinking, and lounging around with newspapers, absentmindedly rubbing toes to the distant clatter of maids cleaning up the debris in the kitchen. He wanted to father their children. He wanted to have little domestic quarrels about curtains, and long conversations about career issues, and exchange bright little secret jokes in whispers about people they both knew.

It was time to be married.

Ramu's decision to supplement his wife-finding efforts with his mother's was a purely practical one. Ma had resources he would never have access to. Ma had a lifetime membership to that hidden, systemic device, specially designed for men in his position: the matrimonial industry, a sinister social syndicate redolent with its own brokers and goons and gossip.

Ma was a blessing. Effectively disguised.

As he'd expected, she shot into action. Ma had first broached the subject of his marriage five years earlier, but had been shouted at for her pains. Mind your own business, Ramu had said. She was doing nothing else, but she didn't tell him that, instead biding her time, waiting patiently for the right psychological moment to bring to her son's disposal a vast arsenal of resources, contacts, and networking facilities. Ma was a one-woman marriage-bureau-in-waiting. Waiting, that is, to match her Long-lived Chiranjeevi with someone else's Very-lucky Sowbhagyavathi; and to print up those invitations: Chi. Ramu, son-of-herself, to wed Sow, girl-from-good-family. Please do come.

This afternoon's conversation, like so many in recent days, was littered with the fruits of her research and followed a pattern that Ramu, with veteran discomfort, was beginning to recognize: Ma, bright, cheerful, animated; himself, uneasy, like a tethered animal sensing a storm; uneasy, and wondering about the forces of nature he had inadvertently released.

"So, what do you think?" she pressed him, as she served him with crisp fried vadas and a cup of tea.

Ramu dragged a vada through the coconut chutney, not willing to commit himself.

"So there is this Sundaram girl," she said, repeating herself. "Very nice. Very pretty. Good choice."

Ramu couldn't sit through it all again without comment. "Pretty? Please, Ma! She has a face like a dog's behind."

"Okay. Not so pretty, then. But a very good family, nevertheless. Very well-to-do. Eat."

She eyed him with speculative hope. "Or there is that othe...

Ramu studied the animated woman in front of him, a slight smile on his lips. And apart from the minor variances: his gender, darker skin color, the carefully trimmed goatee resting on his chin, and the worrisome hairline that danced away from his forehead in the coy manner that plagued so many men in their early thirties, it was practically a Mona Lisa smile--full of mystery and hidden amusement.

The woman, Ashwini, was a recent import to the city, having moved to Bangalore with her parents after living her whole life in Bombay. After a year here, she was still going through withdrawal symptoms, and her conversation was frequently colored with Bombay this and Bombay that and in Bombay we and o god why can't Bangalore? If she were smart, he thought, she would learn that this invariably irritated her listeners, many of whom had lived in other parts of the country and indeed the world, but on the whole had managed to assimilate into this southern city with considerably more grace. One saw her everywhere however, in all the pubs and all the parties, because in addition to her list of nostalgic complaints, she was also armed with a lot of verve and fun. She was up for anything, a good-time charlie, a bustling ball of energy and laughter, a squeal and hug and kiss for everybody, her hips grinding inadvertently but pleasantly against the men she talked to as her bottom swayed happily to passing bits of music.

When she met people at parties, she didn't (as Ramu might) smile, chat, and withdraw from them until the next party. Instead she had the knack of making friends, and (before they knew it) of climbing deep into their lives. Then, there she'd be: visiting, cooing to their children, listening with concern to tales of their mothers-in-law, proffering advice on where to get the best blouse tailor versus the best pant tailor and who caters the best party souffles, all of which she amazingly seemed to know, pulled out of the air of a strange and new city by some inexplicable consumerist osmosis. Every party Ramu attended recently had some contribution by her: Ashwini did the decorations, the hostess would say. Ashwini brought the sweet. Do you like the curtains? Ashwini showed me where to buy them. And all this, of course, to Ashwini's tune of Bombay this and Bombay that.

As far as Ramu was concerned, she was just one of those women one met in the evenings and promptly forgot about in the mornings. It was only recently that his interest had taken a direct and more personal turn.

Now he studied her and realized how self-defeating her actions were. He felt a sudden urge to explain this to her (first, of course, sitting her down in a corner armchair, extinguishing her cigarette, placing her drink on a side table, and waiting for her eyes to focus on him instead of dancing about the room): Bangalore was a strange city, a potpourri of beggars and billionaires and determinedly laid-back ways. People dressed down here, not just on Fridays, but every day, and more so on occasions--and gently derided those who didn't. They spoke of their city's attractions to visitors in tones of disparaging surprise. Oh. You like the weather? Yeah, it's okay. I guess. Cool. Blue skies and all. Cosmopolitan people, you think? Yeah, they're a mixed bag. Different, one-tharah types. Not so hard-and-fast. A chill crowd, like. Doing ultra-cool things chumma, simply, for no reason other than to do it.

"See the software lads," he could say, by way of example. See the software lads shrug off their stock options. (No, no, I'm still a simple saaru-soru rasam-and-rice guy at heart.) See the software lads morph their inner Walter Mitty into Alfred Doolittle (I swear, da, it was just a little bit of blooming luck). See them stab each other in the back trying to prove that they too can please-kindly-adjust, the mantra that the city uses to exact merciless compromise from all of its denizens.

Such self-deprecation appeared modern, with its blue jeans and infotech ways, but was actually a very old courtesy. Deride yourself so others may praise you. Did Ashwini know this? Did she know she was spreading irritation before her like a virus? And here, Ramu found his thoughts slowing to a halt. Perhaps she wasn't. Perhaps no one else was really bothered by it. Actually, until recently, neither was he, previously just swatting her behavior out of his mind as he might a fly. At parties, after all, one met all sorts of people and thought nothing further of it.

Until recently.

"Oh god," Ashwini was saying, "you should just see them, yaar. Everybody does it, all the time. In parties, in bars, in people's houses. You're talking to somebody, and then suddenly, they're doing a line. It's crazy!"

The people listening to the excited pitch of her voice did so with an air of fascinated disapproval, like height-of-empire englishwomen being regaled with missionary tales of naughty hindoo heathens. Ashwini was just back from a trip north, and deeply impressed by the spread of cocaine in polite Bombay society. I mean, she said, you don't see anything like that here. In Bangalore. No indeed, thought her listeners primly, all of whom smoked the occasional joint, but nothing more. They were strictly old-fashioned in that way.

"Did you try any?" someone asked.

"Oh god, no! Even though my friends--from good families, you know, from big industrial families--even though they all kept asking me to do it, I said no. They kept saying: god, you're so cool, so hip, why don't you try it? I said, nothing doing, I'll drink all the vodka and smoke as many joints as you like," said Ashwini, proceeding to demonstrate, "but this, nothing doing! Shit yaar, imagine me doing cocaine!"

Shit, thought Ramu, imagine anyone giving a damn.

Three days later, Ramu left his mother's presence with a vague feeling of doom.

This was not going to work.

Entrusting such a crucial mission to his mother was becoming a farce: like sending someone to the market with strict instructions to buy luscious, juicy fruit, and having them repeatedly, idiotically, come home with boring, healthy-for-you vegetables.

Yet Ramu couldn't extricate himself easily. He was, like any unmonk, a captive of his desires.

In recent months, Ramu had found himself attracted, regrettably, not to the pretty young things he met all over the place (for apart from a fierce desire to shag them, there was nothing else he could imagine doing with them); rather, he found himself being drawn to the wives in his circle of friends. Women his own age, claimed by marriage and scarred by childbirth years before; women who waded comfortably between dirty diapers and smelly spouses and stressful jobs and thieving servants and occasional bright evenings filled with beer and good cheer. They laughed easily with him, without that brittle coquetry that younger, single women offered in the name of flirting. They sometimes shone with all the gloss of a recent visit to the beauty parlor, but were more frequently without makeup, displaying casually hirsute underarms and rough-stubbled legs dressed in old shorts. Yet he was seized with feverish desires to taste the beaded sweat on their upper lips as they frowned over some chore, and to bury his nose and mouth and body in the liquid warmth between their thighs. He wanted to make homes with them. He wanted to fill himself with their comfortable, lazy sexuality. He wanted to spend hours in their kitchens cooking vast and creative Sunday meals with them, and then spend hours more eating and drinking, and lounging around with newspapers, absentmindedly rubbing toes to the distant clatter of maids cleaning up the debris in the kitchen. He wanted to father their children. He wanted to have little domestic quarrels about curtains, and long conversations about career issues, and exchange bright little secret jokes in whispers about people they both knew.

It was time to be married.

Ramu's decision to supplement his wife-finding efforts with his mother's was a purely practical one. Ma had resources he would never have access to. Ma had a lifetime membership to that hidden, systemic device, specially designed for men in his position: the matrimonial industry, a sinister social syndicate redolent with its own brokers and goons and gossip.

Ma was a blessing. Effectively disguised.

As he'd expected, she shot into action. Ma had first broached the subject of his marriage five years earlier, but had been shouted at for her pains. Mind your own business, Ramu had said. She was doing nothing else, but she didn't tell him that, instead biding her time, waiting patiently for the right psychological moment to bring to her son's disposal a vast arsenal of resources, contacts, and networking facilities. Ma was a one-woman marriage-bureau-in-waiting. Waiting, that is, to match her Long-lived Chiranjeevi with someone else's Very-lucky Sowbhagyavathi; and to print up those invitations: Chi. Ramu, son-of-herself, to wed Sow, girl-from-good-family. Please do come.

This afternoon's conversation, like so many in recent days, was littered with the fruits of her research and followed a pattern that Ramu, with veteran discomfort, was beginning to recognize: Ma, bright, cheerful, animated; himself, uneasy, like a tethered animal sensing a storm; uneasy, and wondering about the forces of nature he had inadvertently released.

"So, what do you think?" she pressed him, as she served him with crisp fried vadas and a cup of tea.

Ramu dragged a vada through the coconut chutney, not willing to commit himself.

"So there is this Sundaram girl," she said, repeating herself. "Very nice. Very pretty. Good choice."

Ramu couldn't sit through it all again without comment. "Pretty? Please, Ma! She has a face like a dog's behind."

"Okay. Not so pretty, then. But a very good family, nevertheless. Very well-to-do. Eat."

She eyed him with speculative hope. "Or there is that othe...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherReview

- Publication date2005

- ISBN 10 0755327853

- ISBN 13 9780755327850

- BindingPaperback

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 60.07

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Red Carpet

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. Seller Inventory # 0755327853-2-1

Buy New

US$ 60.07

Convert currency