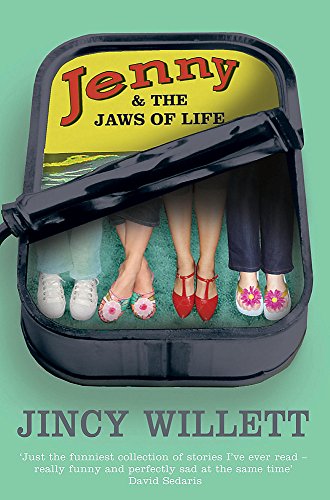

Jenny and the Jaws of Life - Softcover

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Chapter One

The Lingards were not a flashy couple, but people admired and envied their marriage, the symmetry of their mutual regard, their serene and constant intimacy. This perfect marriage was often held up as a standard against which other couples disparaged their own. In a typical argument the wife would say, "Kenneth never cuts her down in public," and the husband would perhaps reply that "Maybe that’s because he respects her, because Anita doesn’t get bombed and blab her husband’s private remarks at parties. And even if Anita couldn’t hold her booze," he might add, with somewhat more fervor, "she’d find some subtle way to let him know that they ought to leave early"; "And if she did," his wife would shout, "he wouldn’t pretend not to notice her"; and so on. Marital tension was high in their close-knit community, where most of the husbands and some of the wives were research immunologists, and the nonprofessional half of the couple (for there was no profession but medicine) was often lonely and alienated because the professional half worked hard and played hard, or worked hard and fell asleep. Had the Lingards not been so amiable, they would have been widely resented, like the one brilliant student who ruins a bell curve. Common wisdom in the group (especially those on their second marriages) held that, while opposites may attract, they repel in the long run, and here again the Lingards were often cited, this time as the exception that proved the rule. He was lean and fair and austere, and she was plump and dark and voluble. To relax, he devised cryptic crosswords, and she practiced her violin, which she played, semiprofessionally, with a local quartet. His intelligence was disciplined and objective, hers unruly and bluntly intuitive. They were absolutely unalike, and yet no one ever wondered what one Lingard saw in the other, or if each Lingard sometimes yearned for the company of its own kind. They had never been known to disagree on any issue of substance, and almost never even on trifling matters of fact. When they spoke, recounting some story, arguing some position, consecutive paragraphs, sentences, even phrases within a single sentence flowed seamlessly between them. And their spontaneous behavior was so often identical and synchronous that, for instance, the Lingard Laugh, sudden and coincident, was a generally recognized phenomenon, and one not too well understood, as the occasion for amusement was often impossible for others to detect. Talking to the Lingards, as Saul Goldberg said, you often felt as though you addressed one person with two faces, like the perfect multilimbed creature of Platonic myth, or the Lingards’ own freakish child. (The Lingards were childless.) Of course no one knew what their sexual life was like—these people were not young, and the Lingards were especially discreet—but friends of both sexes imagined their marriage bed as a sunny place devoid of mystery and strife, their sex foreordained and utterly peaceful, and therefore oddly, and enviably, perverse.In fact, in private fact, the Lingards were so perfectly suited that they were not even aware of the joy they took in each other, joy being their natural state. With other mates they might have known ecstasy, romance, resentment, the thrill and risk of sexual war; they settled, in their ignorance, on kindness and the modest pleasures of companionship. Their sex really was sunny, pleasant, free of effort and ambition. They were mated for life, simply, like greylag geese, and like those plain purposeful fliers they were incapable of imagining any other life but this. They hadn’t the sense to be smug. Which is not to say they were inhuman. Once, while they were driving across Florida, Kenneth told Anita to "Shut up." One morning he said "Look, I don’t want Grape-Nuts" with absurd emphasis, in a querulous voice that saddened and diminished them both. Once when she was practicing the violin, with an all-Beethoven concert upcoming, she told him to fix his own damn dinner. But with a single exception this was the extent of their empathic failure. They were two complex individuals who made a simple miraculous whole. In the middle of a sleepless night, at a boisterous gathering, in front of a television set blaring dreadful news of the perilous world, one would reach out and touch the other lightly, unconsciously, like a talisman. They had only one real fight in twenty years, and that very early in their marriage, when Anita made an offhand remark about her horoscope in the morning paper. "According to the stars," she told him at the breakfast table, "I must avoid undertaking any important projects today." She was trying to think of a way to turn this into a joke when he asked her to repeat herself, as he had been reading the front page. She obliged, feeling a little foolish, since she had not meant anything by it in the first place. Kenneth, who had been up working late five nights running, and who was ordinarily the most easygoing of men, was suddenly outraged that a reputable newspaper would run an astrology column. It was just that sort of bleak, caffeine-driven morning for him: any innocuous thing could have brought on his sudden, hungry outrage. Anita, who agreed that astrology was an insult to the intelligence, made a mild remark about the public’s right to get what they want, even if it’s bad for them. "And anyway," she said, "it doesn’t really hurt anybody." For a long time they seemed not to be arguing at all, but merely carrying on an extended intellectual debate, the locus shifting from breakfast table to kitchen sink while she washed dishes, to the bathroom while he shaved, to the bedroom while they dressed, and at first they seemed mostly in accord, with Kenneth agreeing that people had the right to believe that the world is flat or that you can talk to the dead, and Anita agreeing that it was contemptible for nonbelievers to exploit their folly. But it gradually emerged that they did not see eye to eye on what was folly and what was not: under the general heading of "claptrap" Kenneth included theories of ESP and telekinesis, which Anita had casually assumed were plausible; and when he refused to allow that scientists had any sort of duty to test these theories out she was unpleasantly surprised. Surely, she said, the sighted should lead the blind, and outright fraud should be exposed by those best qualified to do so."That takes time, Anita," said Kenneth, tying his tie. "You can’t expect a Ph.D. to sacrifice a big chunk of his career just because some moron wants to believe that vegetables love chamber music." Anita then supposed she too must be a moron, for she had more or less come to believe in the secret life of plants; and after this the argument became wildly emotional. Kenneth came from a long line of scientists, academics, and agnostics. Anita was the most rational woman in her family. Her mother and her father’s sister had each had out-of-body experiences, her sister was always talking about Velikovsky, and both her grandmothers had met Jesus Christ. Yet except for her sister these women were quite phlegmatic and otherwise sensible, and though she had always felt more intellectually favored than they were, she did not at all like to hear her husband call them "morons." In the end Anita lost control and bitterly reminded him, in barely coherent, tremulous sentence

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherHeadline Book Publishing

- Publication date2005

- ISBN 10 0755304497

- ISBN 13 9780755304493

- BindingPaperback

- Rating

(No Available Copies)

Search Books: Create a WantIf you know the book but cannot find it on AbeBooks, we can automatically search for it on your behalf as new inventory is added. If it is added to AbeBooks by one of our member booksellers, we will notify you!

Create a Want