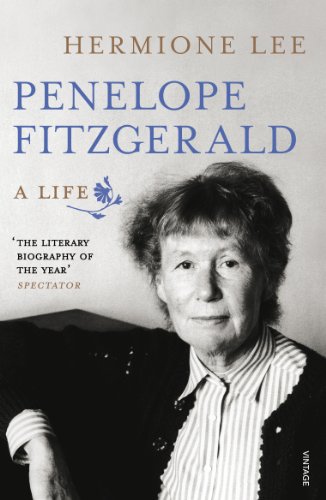

Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life - Hardcover

Penelope Fitzgerald (1916-2000) was a great English writer, who would never have described herself in such grand terms. Her novels were short, spare masterpieces, self-concealing, oblique and subtle. The first group of these drew on her own experiences -- a boat on the Thames in the 1960s; the BBC in war time; a failing bookshop in a Suffolk; an eccentric stage-school. The later ones opened out to encompass historical worlds which, magically, she seemed to possess entirely: Russia before the Revolution; post-war Italy; Germany in the time of the Romantic writer Novalis.

Fitzgerald's life is as various, as cryptic and as intriguing as her fiction. It spans most of the twentieth century, and moves from a Bishop's Palace to a sinking barge, from a demanding intellectual family to hardship and poverty, from a life of teaching and obscurity to a blaze of renown. She started publishing at sixty and became famous at eighty. This is a story of lateness, patience and persistence: a private form of heroism.

Loved and admired, and increasingly recognised as one of the outstanding novelists of her time, she remains, also, mysterious and intriguing. She liked to mislead people with a good imitation of an absent-minded old lady; but under that scatty front were a steel-sharp brain and an imagination of wonderful reach. This brilliant biography -- by a biographer whom Fitzgerald herself admired -- pursues her life, her writing, and her secret self, with fascinated interest.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

The Bishops’ Granddaughter

“Must We Have Lives?”

The Old Palace of the Bishop of Lincoln was freezing cold and full of hectic activity in the winter of 1916. The Bishop’s younger daughter, Christina Frances, had said goodbye to her husband, Eddie Knox, in peacetime a journalist and poet, now second lieutenant in the Lincolns, a regiment he had joined because of its connection to her family home. He was waiting to embark for France. They had been married four years and had a three-year-old son, Rawle. Christina was thirty-one, and heavily pregnant. She and Eddie had set up home in rural Hampstead, but because of the war she had moved into the Palace with Rawle and a young nursemaid, to have their second child under her parents’ care.

But the Bishop, Edward Lee Hicks, and his wife, Agnes, were under strain. They had thrown open the Palace at the start of the war to a group of pitiful Belgian refugees, some of whom were still living nearby and doing odd jobs for them. Lincoln, because it had munitions factories, was a target for Zeppelin raids. The town was full of war-wounded and displaced persons and housewives coping with bereavements, air raids and rationing. The Bishop was shocked to see police controlling huge queues for margarine at the shops. He was working so hard—visiting camps and hospitals, protesting against the ill-treatment of conscientious objectors, giving sermons all over the country—that he had come down with a dangerous attack of the flu. Agnes was doing everything.

He was too ill to see Christina when her baby, Penelope Mary Knox, was born, without much fuss, on the Sunday afternoon of 17 December 1916. The Bishop was still not well enough to officiate at the baptism on 18 January 1917. Penelope Mary was baptised by the Dean of Lincoln, with two aunts from either side of her family (Eddie Knox’s sister Ethel and Christina’s sister-in-law Margaret Alison Hicks) as her sponsors. Her given names, though, were never used by the family. She was always called Mops, or Mopsie, or Mopsa.

The great frost lasted into March. The Bishop had barely recovered from his illness, and his granddaughter was only a few months old, when the news came of his oldest son’s death. Christina’s brother Edwin Hicks caught trench fever at Amiens, then died of an attack of meningitis. The Bishop, a pacifist who opposed the war, asked that “nothing about ‘victory’ should be put on the grave of his dead son.” The young widow, Margaret Alison, married for less than two years, bore up valiantly: this was a comfort to his parents. Weeks later, Bishop Hicks and his family turned the Old Palace over to the Red Cross for a hospital, and moved into a much smaller house, cramped quarters for Christina, her parents, her little boy and the new baby.

In September 1917, Eddie Knox, who had been shooting rats in the trenches, observing “ordinary behaviour under terrible conditions” and finding himself unable to write comic pieces from the front line for Punch, was reported missing. He had been shot in the back by a sniper at the Battle of Passchendaele, then found in a shell hole in a pool of blood. He was invalided out, operated on, and brought to a Lincoln hospital to convalesce. Christina, meanwhile, was playing her part on the home front, looking after the children, helping her father, and organising an exhibition of women’s war work at the local branch of Boots. In April 1919, when Eddie was finally demobbed, she was being visited by the Hickses in a Lincoln hospital for women and children, and was said to be only slowly improving; perhaps she had had a miscarriage. Just then, the Bishop, finally worn out, retired from his duties. He died in August 1919. Christina and her children were at his bedside, but Penelope, aged two, was too young to remember. Nevertheless, Bishop Hicks was a figure who mattered to her, among the bishops, missionaries, vicars and priests thickly scattered through her family tree. She liked the sound of him.

Edward Lee Hicks never refused to see anyone who came to his door for help. He was a great enemy of poverty and injustice, having come, while he was at Oxford, under the influence of John Ruskin. Ruskin he admired, not only for his teaching but also for his delight in even the smallest details of life. Ruskin, he said, would describe “with the keenest relish” the joy of shelling peas:

“The pop which assures one of a successful start, the fresh colour and scent of the juicy row within, and the pleasure of skilfully scooping the bouncing peas with one’s thumb into the vessel by one’s side.” I can honestly say that I never shell peas in summer without thinking of Ruskin and of my grandfather.

Shelling peas was the right association, since the Hickses were originally a farming family. So were the Pughs, the Bishop’s maternal family. The Hickses farmed in Wolvercote, a village on the northern edge of Oxford that looks over Port Meadow and the River Thames. They were an old-fashioned Church of England family who didn’t like Methodists coming into the village. But Edward Hicks, the future Bishop’s father, married Catherine Pugh, a strong-minded person who lived to a great age, one of eleven poor children of a musical Welsh father and a devout Wesleyan mother. Because of his marriage Edward Hicks became a Methodist. So his son Edward Lee Hicks grew up with a mixed religious background. Since the Hicks/Knox families contained Quakers, Ulster Protestants, Wesleyans, Evangelicals, Anglicans, Anglo-Catholics and Roman Catholics, some not on speaking terms with one another, Penelope Fitzgerald developed a belief that religious schisms are pointless, and that all different faiths are really one. She draws attention to this in The Knox Brothers, when calling the faiths that maintained the Knoxes in their dark hours, or “the Bishop of Lincoln’s when his son died in the trenches, or Christina’s when she got a telegram to say that Eddie was missing,” not greater or lesser faiths, “but the same.” Where she agreed with both her grandparents was that faith was necessary for life.

Both Edward Hicks and Catherine Pugh had fathers who died young (Edward’s fell off a ladder pruning a Wolvercote fruit tree), and Edward Hicks, too, died early. An argumentative, musical, generous person, he was a hopeless businessman, who went into debt and died of consumption when his son Edward Lee was nine. Catherine ran the fatherless family, and got Edward Lee into Magdalen School as a chorister. He remembered the shame of being a poor boy at school among richer boys. But he grew up into a scholar and an Oxford don, teaching at Corpus Christi College in the 1860s when Ruskin was there, and when Oxford was, in Fitzgerald’s words, “spiritually in low water” after Newman’s departure and the fiercely divisive Tractarian wars. One of Edward Lee Hicks’s students at Corpus was Edmund Arbuthnott Knox. The Hickses and the Knoxes would keep on interconnecting.

Hicks was ordained in 1870; he was also by then an expert in Greek epigraphy, known at the British Museum for “a happy ability in restoring half-destroyed inscriptions.” So when he was offered the country living of Fenny Compton—a backwater between Banbury and Leamington Spa—for about £600 a year, in 1873, and married a vicar’s daughter, Agnes Trevelyan Smith, he could have settled into a modestly comfortable combination of scholarship, rural ministry and domestic life, with six children (one of whom died in infancy) born between 1878 and 1892.

But Edward Lee Hicks was not an easy-living person. His years at Fenny Compton were a time of agricultural depression and farm workers’ strikes. He sympathised with and worked on behalf of the “land-hungry” labourers. He was a Liberal who believed in grassroots social reform. In the 1880s he and the family moved to a huge, poor parish in Manchester, where he took his double life, as a social reformer and classical scholar, into a tough urban environment. But the move meant that scholarship, the quiet, happy deciphering of Greek inscriptions, had to give way entirely to public work. As Rector at Salford and Canon of Manchester Cathedral, he also wrote polemical pieces—for instance, against the Boer War—for his friend C. P. Scott at the Manchester Guardian. One of the clerics he disagreed with was his ex-pupil Edmund Knox, now his bishop at Manchester, who ran a loud national campaign for the retention of church schools, which were under threat—while Canon Hicks thought that parents should have the right to have their children taught according to their own beliefs.

Some people thought Hicks was too dangerously radical to be made a bishop, and the appointment came late in his life. He had nine years at Lincoln, but he made the most of them. His obituaries called him “a progressive prelate” and “a friend of the poor.” It wasn’t only for his pea shelling that Bishop Hicks admired Ruskin. Ruskin’s dictum—There is no wealth but life—was his own, and he used Ruskin’s attack on the immorality of capitalism, Unto This Last, as a text for his sermons. In “Christianity and Riches,” given at Cambridge in 1913, he preached that the Church suffered from being associated with the comfortable, wealthy classes. But “all must refuse to value anyone the more because of his riches.” His granddaughter, who also admired Ruskin, agreed.

He understood poverty because he had experienced it. Fitzgerald wrote, with feeling, of Bishop Hicks’s family: “Occasionally they would write down a list of all the things they wanted but couldn’t afford, and then burn the piece of paper. This is a device which is always worth trying.” All her life, Christina could never take a taxi without feeling guilty: “cabby” was her word for “expensive.” There were other things, too, she got from her father. Hicks was a feminist, school of John Stuart Mill. He tried unsuccessfully to persuade his fellow bishops to take the clause about “obeying” out of the Marriage Service in the Prayer Book, and he supported women’s suffrage. Christina Hicks inherited those beliefs. Her father gave her, and her brothers and sister, free choices. All the children, Christina wrote eloquently, were encouraged to talk to him as equals. They consulted him as though he were an encyclopaedia. “He never laughed at us, and always contrived to make us feel that we had asked something really interesting.” They were taught that things should be “perfectly simple” but good of their kind—“a book well printed and bound, for instance, that didn’t crack when it was opened.” He liked games, music, walks, funny stories and beautiful objects; he hated tyranny and ugliness. He believed in equal opportunities for boys and girls. When he and Agnes moved to Lincoln in 1910—Christina was then twenty-five, with a university education—she was “offered the choice of going away to make a career for myself, or of being ‘home-daughter,’ whichever I pleased . . . I have never known a daughter so treated, and I have asked many.”

i

We hardly hear that thoughtful, intelligent voice of Christina’s in her daughter’s family memories—either in The Knox Brothers or in other later pieces about her childhood—where the mother mainly exists as a silence or an absence, and appears first as “a gentle, spirited, scholarly, hazel-eyed girl, a lover of poetry and music . . . ready to laugh at herself ” and later as “a quietly spoken woman whom nothing defeated.” In Granny Pugh’s letters to her daughter-in-law Agnes about the children, Christina figures as an admirable granddaughter. In 1896, when she was eleven: “It is grateful to me to hear that Christina is fond of poetry. She always seemed to me a child of promise.” In 1897: “I am so glad that Christina has distinguished herself.” At Withington Girls’ School in Manchester, she took the lead in school plays. In 1904 she got a scholarship for £40 a year to Somerville, one of the first women’s colleges in Oxford.

Her daughter would be amused by the letter which came with the scholarship, “reminding her that she must change her dress for dinner, but ‘must bring no fal-lals, as they only collect dust.’ ” Her tutors thought her “decidedly promising” if a little immature, “animated and intelligent,” with good skills in logic. Helen Darbishire, the Milton and Wordsworth scholar, then senior English Tutor, thought that she wrote with “taste and judgement,” but needed “to cultivate more self-confidence.” She was active on college committees, writing careful minutes as secretary (“Miss Hicks drew attention to complaints which she had received from members whose mackintoshes and umbrellas had been borrowed without permission”) and allowing herself some light moments: “Miss Blake delivered a stirring exhortation on the subject of the Fiction Library” . . . “Rules about Sleeping Out: No one may consciously sleep out in the rain!” She worked hard, went to dances, had a “beau” or two, won the College Coombs prize, made friends with the future novelist Rose Macaulay, and left in 1907 with a Second Class in English, though she could not take her degree until 1921, the year after Oxford at last started awarding degrees to women. Possibly Oxford’s discriminatory attitudes, as well as her father’s support, fuelled Christina’s involvement, in 1908, in demonstrations and mass meetings in support of the Women’s Suffrage Bill.

Her father grieved over Edwin’s death and over the defection of his youngest son, Ned, who, after being wounded on the Somme, converted to Roman Catholicism under the influence of Ronald Knox. But the Bishop was proud of “Tina’s” scholarly achievements. He was close to his younger daughter. When she went abroad after Oxford, he advised her: “Try to use all the chances that come to you of learning about the habits and conditions of the people.” When she asked him about belief, he sent her a long letter, which concluded: “The sound Christian is largely an agnostic.” When he gave her the choice in 1910 of being a “home-daughter” or having a career, she went to teach at St. Felix School in Southwold. The Bishop approved of that as much as he did of her engagement to Eddie Knox, son of his old acquaintance the Bishop of Manchester, in 1912.

Christina and Eddie met in Oxford, probably introduced by her younger brother Ned, who, at Magdalen School, had already brought home an admirer for his sister, his fellow chorister Ivor Novello, who on family holidays followed her about devotedly. Nobody wanted the engagement to be long. One sensible bishop’s wife, Mrs. Hicks, conferred with the other, Mrs. Knox: “Christina says . . . it does seem such a long time till May! She is anxious because he is lonely . . .” They were married in St. Hugh’s Chapel in Lincoln Cathedral on 17 September 1912. It was a family affair.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherChatto & Windus

- Publication date2013

- ISBN 10 0701184957

- ISBN 13 9780701184957

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages528

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.80

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # JV-06E9-RGSS

Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks146771

PENELOPE FITZGERALD

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: Brand New. 528 pages. 9.45x6.38x1.73 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # zk0701184957

Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Dust Jacket Condition: New. First UK edition-first printing. Mint condition.Chatto and Windus,2013.First UK edition-first printing(2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1).Blue hardback(gilt lettering to the spine) with Dj(small nick on the edges of the Dj cover),both in mint condition.Illustrated with b/w photos,drawings.The book is new.519pp including List of illustrations,family tree,abbreviations,notes,index.Price un-clipped.Heavy book(approx 1.2 Kg). This is another paragraph Book Description: Penelope Fitzgerald (1916-2000) was a great English writer, who would never have described herself in such grand terms. Her novels were short, spare masterpieces, self-concealing, oblique and subtle. She won the Booker Prize for her novel Offshore in 1979, and her last work, The Blue Flower, was acclaimed as a work of genius. The early novels drew on her own experiences - a boat on the Thames in the 1960s; the BBC in war time; a failing bookshop in Suffolk; an eccentric stage-school. The later ones opened out to encompass historical worlds which, magically, she seemed to possess entirely: Russia before the Revolution; post-war Italy; Germany in the time of the Romantic writer Novalis. Fitzgerald's life is as various and as cryptic as her fiction. It spans most of the twentieth century, and moves from a Bishop's Palace to a sinking barge, from a demanding intellectual family to hardship and poverty, from a life of teaching and obscurity to a blaze of renown. She was first published at sixty and became famous at eighty. This is a story of lateness, patience and persistence: a private form of heroism. Loved and admired, and increasingly recognised as one of the outstanding novelists of her time, she remains, also, mysterious and intriguing. She liked to mislead people with a good imitation of an absent-minded old lady, but under that scatty front were a steel-sharp brain and an imagination of wonderful reach. This brilliant account - by a biographer whom Fitzgerald herself admired - pursues her life, her writing, and her secret self, with fascinated interest. Seller Inventory # 7725