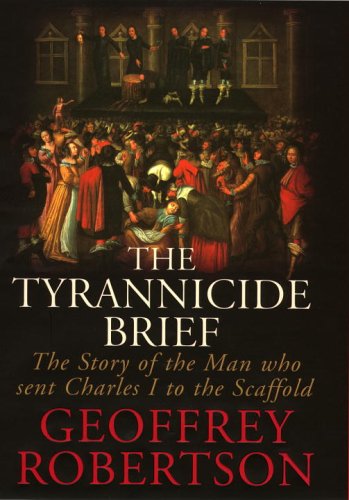

The Tyrannicide Brief: The Man Who Sent Charles I to the Scaffold - Hardcover

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

This mattered so much to these Puritan parents that for the baptism of their first-born they had travelled from their own farm, just outside Burbage, where the rector was a well-connected Anglican who obeyed the bishop, to Elizabeth’s austere family church. Its minister was willing to dispense with ‘impure’ rituals, like motioning the sign of the cross over the head of the baptised infant. That such a tiny gesture could become a major bone of contention between the bishops of the Church of England, who were sticklers for rituals and symbols, and those Puritan worshippers who wished to ‘purify’ the Church of all such distractions, was typical of the internecine squabbling that had rent the Anglican religion. Puritans like the Cookes were thick on the ground in the Midlands and the eastern counties and many local ministers were sympathetic to their preference for deritualised worship, which was anathema to King James and his bishops.

James I had been invited from Scotland (where he ruled as James VI) to take the English throne on Elizabeth I’s death in 1603. The optimism among Puritans in England that a man from the austere Calvinist Kirk would look sympathetically on their similar form of worship had soon been dashed: James was obsessed with his God-given right to rule as an absolute prince, through a hierarchy supported by archbishops and bishops, alongside his councillors and favourite courtiers. From the outset of his reign he urged the Anglican authorities to discipline ministers who refused to follow approved rituals or who spoke on politics from the pulpit. James I was very far from being ‘the wisest fool in Christendom’: he was highly educated and very canny, and he knew exactly where the Puritans’ hostility to hierarchy in their church would lead: ‘no Bishop, no King’.

James warned his son to ‘hate no man more than a proud Puritan’. He did not persecute them, but encouraged the Church to discriminate against them and to sack their ministers. The King’s edicts, on matters of Sunday observance in particular, were often at variance with the strict moral code of these godly communities, and the profligacy and debauchery of his court further outraged them. As John Cooke grew up, there was much prurient gossip amongst the faithful about a monarch who claimed divine authority yet who maintained a luxurious and licentious court, financed by selling titles and monopolies, and who boasted that his favourite pastimes were ‘hunting witches, prophets, Puritans, dead cats and hares’. After all, James had a grotesque parentage: his mother was Mary, Queen of Scots. He was in her swollen belly when it was clutched at by her lover, David Riccio, as he was being dragged to his death at Holyrood House by a team of assassins led by James’s father, Henry Stuart. Mary had later arranged for Henry to be strangled and had eventually been executed for plotting to kill her cousin and sister-queen Elizabeth I. If there was anything in the theory of hereditary right by which James acceded to the throne, it did not bode well for the Stuarts.

The farming community where the Cookes lived was small – there were only seventy families at Burbage (then named Burbach) and a handful in their hamlet of Sketchley. The town’s name – a construct from ‘burr’ (a kind of thistle) and ‘bach’ (a rivulet) – indicates the kind of countryside in which he played as a boy, although play was not encouraged by Puritans: they had been outraged when James issued a ‘Book of Sports’, permitting certain recreations after church on Sundays. As a young man, Cooke was well aware that the brand of religion on which he was raised was not in government favour. At school, where he excelled, he belonged to a group of Puritan children ostracised in the playground just as their parents were often excluded from worship in the church. There was one faith that suffered worse discrimination: the stateliest house in the area, Bosworth Hall, was owned by a Catholic family related to Sir Thomas More, and their secret celebration of Mass was the cause of occasional raids authorised by the local Justices of the Peace. Especially after the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, Catholics were regarded as potential terrorists, but the strength of their faith intrigued the boy, and would later tempt him to explore it before settling on his own. He spent long hours learning the Bible (the King James edition was printed in 1611, and widely distributed) and was brought up to believe that powerful men who had failed God’s election were abandoned to sin – a belief readily corroborated by reports of corrupt behaviour at court.

James, more homoerotically fixated as he became older, elevated his young male favourites (first Robert Carr, then George Villiers) to titles and positions of power entirely beyond their abilities. Scandalous rumours were rife throughout Cooke’s youth, confirmed by trials in 1616 which gripped the nation. The Countess of Essex, married to Robert Carr whom the King had made Earl of Somerset, arranged for Sir Thomas Overbury to be murdered, by having arsenic put in his food and then, when that failed, by administration of an enema filled with poison. Various of the poisoners were convicted and hanged, but not the earl or the courtiers who had procured the murder, who were pardoned because of their status. Puritans got the message: although their birth might be low on the social scale, in death God would raise them far above kings and courtiers. Another message – that there was no justice to be had in the King’s courts, at least in cases concerning the King and his favourites – would soon concern a new generation of lawyers for whom the common law of England, rooted in Magna Carta, brooked no such exceptions.

Another telling event of Cooke’s youth was the execution in 1618 of Sir Walter Ralegh, that great Renaissance Englishman – historian, explorer, poet, philosopher, intellectual and adventurer. He had been convicted in 1603 on trumped-up charges of plotting with Spanish interests to overthrow the newly crowned King James. His treason trial had been notable for the invective of the prosecutor, the ambitious Attorney-General Edward Coke:

Coke: You are the most vile and execrable traitor that ever lived.

Ralegh: You speak indiscreetly, uncivilly and barbarously.

Coke: I want words sufficient to express your viperous treasons.

Ralegh: I think you want words indeed, for you have spoken one thing half a dozen times.

Coke: You are an odious fellow; your name is hateful to all the realm of England . . . I will make it appear to the world that there never lived a viler viper on the face of the earth than you.

This abuse of the defendant was what passed for cross-examination in treason trials, after which jurors who had been hand-picked by the King’s officials were expected to convict. This time, unusually, Coke’s venom backfired: Ralegh’s dignity earned him such popular support that James, cautious at the outset of his reign, felt it politic to suspend his death sentence. Sir Walter lived in modest comfort in the Tower of London, in rooms that can still be viewed, and was released in 1616 to mount an expedition in search of Spanish gold. It was unsuccessful, but it rekindled Spain’s hatred of the man who had sunk so many of its galleons and had razed Cadiz. His execution was demanded as a condition of fulfilling James’s pet project of marriage between his own heir (Charles) and the Spanish princess. James could hardly put Ralegh on public trial for attacking England’s traditional enemy: instead, he ordered his Chancellor, the brilliant but bent Francis Bacon, to arrange to have the 1603 death sentence put into effect. Ralegh went to his long-delayed execution with memorable dignity, after a scaffold speech which persuaded everyone of his innocence and which convinced two of the onlookers – the MPs John Eliot and John Pym – that the Stuarts could not be trusted to govern the country. James was depraved, unpopular and idle: now he had killed an English hero at the request of Spain. There remained a general belief that he had been appointed by God, but by the end of his reign it had occurred to many MPs to examine more closely the terms of that divine appointment.

James had only one male heir, the small (5 feet 4 inches), stammering and petulant Charles, born in 1600. He was made Prince of Wales in 1616, after the death of Henry, his more popular elder brother. While John Cooke spent his boyhood in the bosom of a l...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherChatto & Windus

- Publication date2005

- ISBN 10 0701176024

- ISBN 13 9780701176020

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages429

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 17.50

From Canada to U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Tyrannicide Brief

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Dust Jacket Condition: New. 1st Edition. Seller Inventory # 009789

The Tyrannicide Brief: The Man Who Sent Charles I to the Scaffold

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0701176024

The Tyrannicide Brief: The Man Who Sent Charles I to the Scaffold

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0701176024

THE TYRANNICIDE BRIEF: THE MAN W

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.68. Seller Inventory # Q-0701176024

The Tyrannicide Brief: The Man Who Sent Charles I to the Scaffold

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0701176024