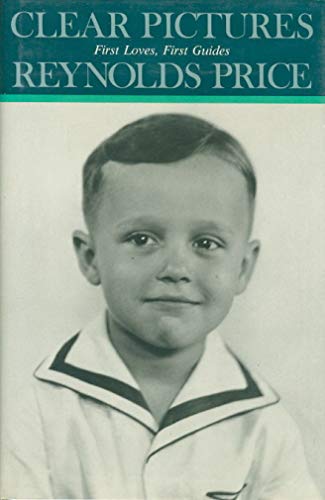

Clear Pictures: First Loves First Guides - Hardcover

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Chapter 1

THREE USEFUL LESSONS

WILL AND ELIZABETH PRICE

I'm Lying In Dry Sun, alone and happy. Under me is a white blanket. I'm fascinated by the pure blue sky, but Topsy the goat is chained to my right -- out of reach they think. The sound of her grazing comes steadily closer. I've sat on her back, she pulls my cart, I'm not afraid. Suddenly though she is here above me, a stiff rank smell. She licks my forehead in rough strokes of a short pink tongue. Then she begins to pull hard at what I'm wearing. I don't understand that she's eating my diaper. I push at her strong head and laugh for the first time yet in my life. I'm free to laugh since my parents are nearby, talking on the porch. They'll be here shortly, no need to cry out. I'm four or five months old and still happy, sunbathing my body that was sick all winter.

That scene is my earliest sure memory; and it poses all the first questions -- how does a newborn child learn the three indispensable human skills he is born without? How does he learn to live, love, and die? How do we learn to depend emotionally and spiritually on others and to trust them with our lives? How do we learn the few but vital ways to honor other creatures and delight in their presence? And how do we learn to bear, use and transmit that knowledge through the span of a life and then to relinquish it?

I've said that all but one of my student writers have located their earliest memory in the third or fourth year. My own first memory appears to be a rare one. The incident was often laughed about in my presence at later gatherings -- the day poor Topsy went for Reynolds's diaper, got a good whiff and bolted. So I might have built a false memory from other people's narratives. But I'm still convinced that the scene I've described is a fragment of actual recall, stored at the moment of action. If it wasn't I'd have embellished the scene further -- adding clouds to the sky, a smell to the grass, the pitch of my parents' voices. What I've written is what I have, an unadorned fragment that feels hard and genuine. And the only trace of emotion is my lack of fear, my pleasure, both of which produced my first awareness of dependency -- the goat won't eat me; help is near.

From the presence of Topsy, I know I'm in Macon, North Carolina. She was born, the same day as I, on my Uncle Marvin Drake's farm up near the Roanoke River. My father has had a small red goat-cart built, big enough for me and one child-passenger; and Topsy is already strong enough to pull us. Since we left Macon before I was a year old, then the memory comes from my first summer in 1933. That February 1st, I'd been born in the far west bedroom of my mother's family home in Macon.

Macon was then a village of under two hundred people, black and white. Because it was an active station on the Seaboard Railroad's Raleigh-to-Norfolk line, it had grown north and south from the depot in the shape of a Jerusalem cross-a north-south dirt street, an east-west paved road parallel to the train tracks and a few dirt streets parallel still to both axes.

There was a minuscule but thriving business district -- three grocery and dry-goods stores, a gas station and a post office. There were two brick white churches, Methodist and Baptist, and two frame black churches, one on the west edge and one in the country. There were fewer than forty white households, mostly roomy but unpretentious frame houses, no pillared mansions. A few smaller black houses were set in the midst of town with no hint of threat or resentment; but most black families lived on the fringes of town -- some in solid small houses, some in surprisingly immortal-seeming hovels. And on all sides, the sandy fields of tobacco and cotton lay flat and compliant, backed by deep woods of pine and cedar and big-waisted hardwoods.

Almost every white family employed one or more black women, men and children as farm hands, house servants, yardmen, gardeners and drivers. With all the deep numb evil of the system (numb for whites)-slavery and servitude did at least as much enduring damage to whites as to blacks -- those domestic relations were astonishingly good-natured and trusting, so decorous that neither side began to explore or understand the other's hidden needs. When they'd granted one another the hunger for food, shelter and affection, their explorations apparently ceased; and the ancient but working standoff continued.

Yet a major strand of the harmony of all their lives consisted of the easy flow of dialogue expressive of mutual dependency, jointly sparked fun and the frequent occasions of mutual exasperation. There were even glints of rage from each side; but in our family homes at least, there was never a word about the tragic tie that bound the two peoples. And if a cook or yardman mysteriously failed to appear on Monday morning, even the kindest white employer was sure to foment angrily on the blatant no-count ingratitude -- no trace of acknowledgement that a bonedeep hostile reluctance might be fuming.

Since the family trees of strangers are high on anyone's boredom scale, I'll limit the following to what seems bare necessity if I'm to track these mysteries. My mother Elizabeth Martin Rodwell was born in 1905 and reared in Macon in the oak-shaded rambling white seven-room house built by her father in the mid-1888os. He was John Egerton Rodwell, station master of the Macon depot. He'd grown up in a big nest of brothers on a farm, some four miles north, between Macon and Churchill. His mother Mary Egerton, whether she knew it or not, could have claimed descent from the English family that commissioned John Milton to write his masque Comus in 1634 to celebrate the elevation of John Egerton, Earl of Bridgewater, to the Lord Presidency of Wales (the leading player in Comus was his daughter Alice Egerton, age fifteen). While the memory of such a standing was retained by a few of the deep-country farmers my Egertons had become, after two centuries in slaveholding Virginia and North Carolina, they seldom bragged on their blood.

My mother Elizabeth's mother was Elizabeth White -- called Lizzie, even on her gravestone -- from the oldest continuously settled part of the state, Perquimans County in the northeast corner, eighty miles east of Macon. Lizzie's mother had died in Lizzie's infancy, and she had been reared by her storekeeper father and an agreeable stepmother. On a visit to friends in Macon, she met blackhaired, brown-eyed funny Jack Rodwell; and she married him soon after. She was all of sixteen, mirthful and pleasantly buxom (a later problem), not pretty but widely loved for her good talk, her endless self-teasing and much ready laughter.

She was fated to bear eight children in twenty years, seven of whom survived her. One boy died in his first year; the other three left home early, in the common Dickensian fashion. They packed their small belongings, kissed their parents (all my kin flung themselves on kisses with the recklessness of Russian premiers), flagged the train and headed up the line for railroad jobs in Norfolk, already a teeming port of the U.S. Navy. Of the four daughters, my mother Elizabeth was the youngest. Lizzie used to claim that Elizabeth was conceived because, well after Lizzie thought she was done, the Seaboard added a four a.m. express. Its window-rattling plunge through the heart of Macon would wake Jack nightly and leave him with nothing better to do in the dark than turn to his mate.

My father William Solomon Price was born in 1900 in Warrenton, the small county-seat five miles from Macon. Before the Civil War, the town was a social and political center of the state (a local statesman Nathaniel Macon was Speaker of the House of Representatives in the presidency of Thomas Jefferson). As such it was the home of wealthy slaveholding planters, many of whose elegant houses have lately been refurbished, though Warrenton now shares the sad lot of all bypassed farm towns -- its children leave.

Will's father -- Edward Price, a famed dry wit -- was a son of the town carriage-maker, of Welsh and Scottish stock; Edward's mother was a Reynolds from Perth, Scotland. Barely out of boyhood and balked by Reconstruction poverty from his hope to study medicine, Edward avoided the family business and clerked for the remainder of his life in the county's Registry of Deeds. Will's mother was Lula McCraw, also of Warrenton and the descendant of Scottish, English and French Huguenot immigrants. One of her third-great-grandfathers was James Agee, a Huguenot whom we share with our Tennessee cousin, the writer James Agee. Lula Price was small, with a bright voracious mind, watchful as a sparrow and capable of winging a startlingly ribald comment from behind her lace and cameo with such swift wit as to leave the beauty of her face unmarred. Her short narrow body bore six strong children, all of whom survived her; yet she found the energy to run a ten-room house generously, almost lavishly, on her husband's modest income with a strength of mind and hand that, again, her white-petal beauty belied.

My parents met six years before their marriage. The meeting was in 1921 when Will was twenty-one and Elizabeth sixteen. They'd each gone to a dance at Fleming's Mill Pond, with other dates -- Will with Sally Davis, Elizabeth with Alfred Ellington. Elizabeth's date introduced her to Will; and despite Sally Davis's beauty and wit, an alternate circuit at once lit up. First, both Will and Elizabeth looked fine and knew it, within reason. Second, they were both storage batteries of emotional hunger and high-voltage eros. And third, their short pasts -- which felt like eons -- had left each one of them craving the other's specific brand of nourishment.

Will had graduated from high school four years earlier and had since held easy jobs, none of which required him to go more than a few hundred yards from his family home, while continuing to sleep and board with his parents. His two elder brothers had gone as far as was imaginable then, to Tennessee; but all three of his witty and unassuaged sisters were still in place -- the eldest having left her husband and returned unannounced at the age of twenty with a young son to live for good in the shadow of her father, whom she loved above all and whose deathbed pillows were found in her cedar chest at her own death, more than fifty years later. Both Will's parents were in hale, testy, often hilarious control; so the house contained eight Prices in five bedrooms, plus at least one cook and a handyman.

I can hardly think how a healthy young man, between the ages of seventeen and twenty-seven, can have stood to inhabit such a crowd of watchers and feeders -- and stood them, day and night, for ten years after finishing high school -- but stand them he did. As the youngest son, Will was his mother's "eyeballs." And later evidence suggests that she unconsciously mastered his growing dependence on alcohol to keep him close to an all-forgiving bosom (Elizabeth told me, late in her life, that "Will's mother would ride with him to the bootlegger when no one else would go").

For whatever reasons, Will's extrication from the grip of such a rewarding and demanding mother -- and from his fondness for Sally Davis -- took him six long years of fervent courting. And once he and Elizabeth had steeled themselves, they married as far from Warren County as they could go and still be sheltered by kin. Elizabeth's nextoldest, and favorite, brother Boots gave her away in Portsmouth, Virginia; and in Warrenton, Will's sisters rose at dawn to set all the clocks in the Price house an hour ahead. Then at "noon" -- as the distant vows seemed imminent and their mother announced her imminent heartspell -- they could say "Just calm yourself, Muddy; it's too late now. Will and Elizabeth are a whole hour married and on the train." And so they were -- the Orange Blossom Special, in a "drawing room" suite (courtesy of Elizabeth's Seaboard brothers) and bound for Florida, one of the gorgeous ends of the Earth in those grand days.

Elizabeth's parents had died young. When my mother was eleven, Lizzie's kidneys failed; and Elizabeth was led to her mother's deathbed-surrounded by galvanized tubs of ice to cool the fierce heat -- for a final goodbye. Three years later, sitting on her own porch, Elizabeth looked up the dirt road to see a mail cart from the depot roll toward her. It bore her last anchor -- Jack Rodwell her father, dead of his second stroke at fifty-eight.

From the age of eleven, Elizabeth and her sister Alice, called Britsy and five years older, were mothered by their kind sister Ida. Ida was eighteen years older than Elizabeth; and with her came her then-volatile husband Marvin Drake and their three boys. Though they were Elizabeth's near-contemporary nephews, they quickly became her surrogate brothers, foster sons and chief playmates.

The Drakes had moved in at Lizzie's death to keep house for Jack and the girls; and once Jack died, they stayed for good. Ever after, Elizabeth's feelings about the years of at-home orphanhood were understandably mixed. She was grateful for the chance to remain in her birthplace with mostly well-intentioned kinfolk. But on rare occasions in my own childhood, I'd see her ambushed by sudden resentment. In those short forays, she'd glimpse the worst -- she'd been dispossessed in her rightful place by an interloper with a cold eye for gain, a brother-in-law (who would ultimately purchase the Rodwell children's shares in the home and will it and all its Rodwell contents to his Drake heirs). In a few days though, I'd hear her say "Let's drive up home and see Ida and Marvin." In her best mind, my mother knew they'd kept her alive.

Will and Elizabeth were reared then in classic, though healthily honest, family situations where blood-love, or at least loyalty, was the binding principle of a majority of the by-no-means happy populace. As an inevitable and paradoxical result, my young parents were primed for another love, private but transcendent, that would lead them out of the blighting shadows of their homes into the glare of their own graceful bodies in one another's hands, worked as they were by aching need.

The repeatable public stories of their courtship were among my own favorites from their long repertoire. There was the night when, returning from a performance of The Merry Widow in Henderson, Will left his Model A Ford for a moment to buy cigarettes; and Elizabeth, still too well-mannered to mention a body-need, was forced to lift the floorboard and pee quickly on the hot gear box. It reeked mysteriously through the rest of Will's evening. Or the time the same car got bogged in quicksand and almost sank them. Or the hard days of Will's terror when Elizabeth suffered a ruptured appendix, twenty years before the discovery of antibiotics, and was rushed in agony from Macon to Norfolk on a stretcher in the baggage car of a train -- the only place she could ride flat -- for six weeks of desperate but successful remedies. Or Elizabeth's happiest memory of her strongly ambivalent mother-in-law -- the time they were driving alone together, struck a turkey, killed it neatly and brought it home to eat. Or ...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherCharles Scribner's Sons

- Publication date1989

- ISBN 10 0689120753

- ISBN 13 9780689120756

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages288

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.50

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Clear Pictures: First Loves, First Guides

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Dust Jacket Condition: New. First Edition (1st printing). This is a New and Unread copy of the first edition (1st printing)l. Seller Inventory # 026418

Clear Pictures: First Loves First Guides

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0689120753

Clear Pictures: First Loves First Guides

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0689120753

Clear Pictures: First Loves First Guides

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks191001

CLEAR PICTURES: FIRST LOVES FIRS

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.4. Seller Inventory # Q-0689120753

Clear Pictures: First Loves First Guides

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0689120753