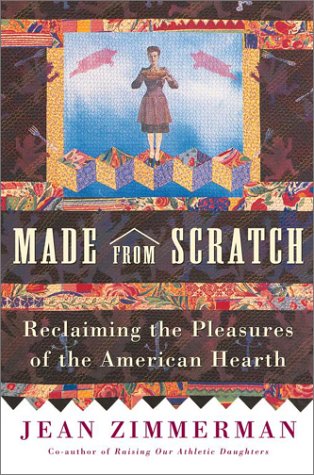

Made from Scratch: Reclaiming the Pleasures of the American Hearth - Hardcover

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Chapter One: Heirlooms

My grandmother, born in 1913, was the last of the old-fashioned American homemakers. A farm wife, she lived her whole life in small-town western Tennessee, midway between Memphis and Nashville, near the border of Kentucky. Her family was close-knit. My grandmother was raised next door to her own grandparents, catty-corner from the house in which her future husband grew up, and together my freshly married grandparents settled on that same block, first in the little house where my mother was born and then in a classic sprawling Victorian conveniently situated next door to my grandfather's first business, a filling station.

Not a soft, big, maternal type, my grandmother was bird-small yet not breakable. She was fashionable, never dowdy. Yet despite her stature and her style, my grandmother embraced the heavy labor of farm life. My grandparents planted fields of feed corn and cotton, soybeans, and okra on farmland outside of town. At the farm, coarse-haired hogs rooted in a pen, and up a rutted muddy road grew a vast peach orchard. Summers, my mother and her sisters and brother helped the field hands harvest strawberries, hunching on their hands and knees over the easily damaged fruit. All of the picking was hard: fuzzy okra pricked the fingertips, and cotton sat like a boulder in the canvas bag slung over the shoulder. Standing sentry behind a big wooden table, my grandmother would count the slatted produce carriers as the pickers brought in each harvest.

Hers was a country life, hard and simple, with one foot planted back in the nineteenth century. Even years later, sending my grandparents letters was easy: the only address required was their name and "Greenfield, Tennessee." You could add "Main Street" if you wanted to get fancy, but the information was unnecessary, a letter would get to them without it. When my mother called home after moving away, the town switchboard operator didn't need to hear her name to connect her with her parents' house.

By 1920, the number of Americans living in cities for the first time outweighed those living in the country, down from 95 percent of Americans who lived in farm country in 1776. A wood stove or a spinning wheel had disappeared from almost every American household, and nearly every home had electricity. In rural Tennessee, though, some things that defined the labor of women like my grandmother hadn't changed. Up through the 1940s she kept a horse and a milk cow in the yard under the catalpas and churned butter in a big ceramic crock on the back porch. Apple and damson trees supplied fruit both for eating fresh and for putting up. The family lived a few blocks from the grocery store, but fresh meat wasn't something you bought. In fall a pig from the pen would be slaughtered for its lard and to send to the barbecue pit. My grandmother's job included wringing the neck of the chicken for every platter of fried chicken she put on the table.

My grandmother sewed all the clothes for her children, selecting fabric at E. and J. Brock, the old general store that sold yard goods. Sometimes she would create matching outfits for herself and all three daughters. Walking to town on a Saturday night as teenagers, the girls would model their homemade dresses, stepping across the railroad tracks that sliced through town under the water tower with GREENFIELD in giant block letters on its side.

A woman named Elrina lived with her husband in a small wooden shack in the corner of the back lot behind the house, and she helped out in the kitchen. Mostly, though, my grandmother herself dished up the stewed tomatoes, chicken-fried steak smothered in milk gravy, black-eyed peas, collard greens, and dinner rolls. This was food that was made from scratch, homegrown and in some cases hunted down. One Thanksgiving when I was a child, my grandmother roasted a wild turkey that my grandfather had killed and my mother cracked a tooth on a pellet of buckshot. Opening the refrigerator to find a cold drink on a summer afternoon, I discovered skinned squirrels in Tupperware and was told that Grandpa shot them out of the trees in the backyard.

Through the 1950s and 1960s, as the world around them convulsed with social changes, my grandparents still lived close to the land. Something seemingly eternal, never changing, was the shared assumption that care of the home was a woman's responsibility as well as a source of accomplishment that deserved respect.

My grandmother inherited the mantle of homemaker from her own mother and her mother's mother. I spent afternoons at the house of my great-grandmother, where we drank grape soda and watched Art Linklater on the black-and-white TV. We took a photograph the summer I turned twelve that we called "the four generations": my great-grandmother, grandmother, mother, and myself. The dress I wore, my favorite dress, had strips of lace, factory-made lace, crossed on the moss green front like the ribbon on a present. I didn't know then that Granny herself was a lace maker, that her house was where the real needlework took place, where she spun intricate webs of polished-cotton thread. I knew Granny in her nineties, with a head of old-timey white pin curls and crepey white arms. I didn't know the richness of the craft life she'd led. The exquisite work that came from her hands was already antiquated, not worthy of mention.

The places don't exist anymore, but the material objects that inhabited them are touchstones of my memory that help define an ideal of home: the orderly, shady house of my grandmother with its Dresden figurines and porch glider, its frigid metal drinking cups with drops of condensation down their sides, the crochet hooks of ivory and aluminum and a skein of plain brown wool, the pecan shells crackling underfoot out front. I can smell the tomato vines in the back garden, picture the speedy flight of purple martins at the towering birdhouse my grandfather built, hear the warble of the quails the neighbors kept in a chicken wire hutch. In my own attic now, a dusty cardboard box still shelters some of the most stunning relics of my family's domestic history -- the dozens of linens elaborately handworked by my grandmother and my great aunt, my great-grandmother, and her mother before her.

***

My mother hastened away at age 17 from the swollen heat, the mute burgeoning physicality of small-town Southern life. She had never worn a store-bought dress until she went to college. Now she eagerly created a new identity for herself that would not include home-sewn clothes, hand-picked strawberries, or chickens whose necks were wrung in the backyard. At an East Coast women's college she studied art history and then married an Ivy Leaguer, the prototypical man in the gray flannel suit who commuted every day to a Manhattan advertising firm. At home in our one-step-down-from-Cheever suburb, my mother hosted cocktail parties and traded PTA responsibilities with other women, but most of her time was spent as was her mother's before her -- buying, preparing, and serving food, cleaning her house and keeping up her property, and attending to the clothing and other needs of her family. With all her smarts and sophistication, in these responsibilities she hadn't come all that far from the lives of her foremothers. Still, though her daily routine wasn't exactly what she had planned in her studious college days, she saw it as an improvement upon the backwater housewife's role she had escaped. She knew she didn't want a farm life. She had watched her mother and her aunt and grandmother sew, and thought it way too laborious, not to mention dull -- all those finishing seams you had to learn, when you could be reading instead.

My mother came from the postwar generation of suburban housewives that Friedan described so well. These highly educated, increasingly frustrated women understood from intense personal experience that change was needed -- indeed, that it was already under way. Economic forces were pushing women into the workplace, and the women's movement was providing the political underpinnings for the push. Housewives, however, harbored the piercing fear that as the world around them moved ahead, they might be left behind, stranded between the domestic assumptions of the past and the unknown ways of the future. Women who gave birth to the baby boom generation may have wanted no part of the traditional life of the home, the life lived by women like my grandmother, and yet many of them performed its day-to-day labors to a tee in studied replication of the past, with the anodyne in many cases of Valium or vodka.

My own mother, with her ikebana and spotless carpets, obsessing over the cleanliness of our Formica countertops, was likewise trapped (in the unshakable opinion of her adolescent daughter). She had the distaste for home-sewn clothes that comes naturally to anyone who has grown up wearing nothing else. Nonetheless, she was perfectly capable of hemming my school jumpers, her mouth bristling with pins. She maintained a well-ordered sewing box and recognized the importance of darning a sock, positions I gradually came to consider quaintly anachronistic if not downright pathetic.

My family endorsed the recognized hierarchies of the day. My father had the "real" job that took him out of the home. His kitchen skills were limited to boiling an egg and making toast. My mother put dinner on the table for a family of five every day for over twenty years, which effort was within my family certainly not considered a "job" at all but a rote accomplishment, given no more notice than the weather. Good homemade spaghetti sauce and beef-barley soup emerged from my mother's kitchen, and even fudge tunnel cakes and carrot cakes when baking them was fashionable in our community. Her goal, though, was to escape enslavement by a hot stove. She didn't go out of her way to tutor me in the kitchen only because she didn't want me to get stuck there, the way some women will say they refused to learn to type because they never wanted to become secretaries.

My mother rejected the farm life of her mother and of all the small-town matrons who predated her. Yet she wasn't ready to abandon the home. Dust free and immaculate, our house was my mother's clear domain. Though she hired cleaning help when she could afford to, its care was still undeniably her responsibility, and her pride.

As I watched, growing up, my mother tried to cobble together the abyss between the past and the future. Attempting to make sense of her experience, I shaped an apocryphal theory that went like this. Yes, she kept a beautiful home. In so doing, she transferred her intelligence and taste from a possible professional career to the so much more mundane reality of creating a domestic life. This was really a tale of wasted talent, unnecessary "sacrifice."

The story's message was simple and oddly like my mother's before me: I must get out.

***

What has made it possible for the home to be an arena of caring, as in my house growing up, is, of course, the labor of women. In the women's studies courses offered in college in the late 1970s, when I was in school, we learned that women had been "inculcated" to be homemakers and to produce that labor, and that this was a bad thing. At Barnard, our texts were Tillie Olsen and The Feminine Mystique; going back further, we read Charlotte Perkins Gilman's The Yellow Wallpaper, the nineteenth century novella about a woman driven to despair and madness by her imprisonment in a domestic role. I soaked up Simone de Beauvoir's argument that women's lives, with their mindless daily chores, did not provide for the kind of daring and adventurousness necessary for exploring and creating important innovations in the world. Her stance on homemaking was adamant: "We have seen what poetic veils are thrown over her monotonous burdens of housekeeping and maternity: in exchange for her liberty she has received the false treasure of her 'femininity.'"

The women's movement of the 1970s cleaved the world of work into two parts. One part, the public part, the "male" part, was deemed vital, engaging, and valuable. The other part, the part left behind in the house dust, the work of the home, was meaningless, humdrum, the stuff of subservience. The division of labor between women and men, I came to believe, was inherently unfair. This translated into a devaluation of women's prescribed jobs along with the mandate that women were supposed to get out of the house and plunder a piece of what in the past had been almost exclusively a male domain. Entering the workplace in the early 1980s, I felt the powerful cultural tug of this idea, being employed, as I was, at a nonprofit think tank devoted to helping women climb the corporate ladder.

That men should likewise venture into the domestic world was only vaguely endorsed and articulated, centering on the demand that they do their fair share of the dishes. In 1983, when I was in my mid twenties, Esquire published a feature extolling the "vanishing American housewife," picturing an example of that endangered species on her knees, smiling brightly, cleaning a toilet bowl. I remember feeling that only an idiot (or a sexist pig) would believe that women were doing something important in the home. Home was a place from which women were to be liberated.

The academic style of feminism that nurtured my generation -- the baby boomers who are now pushing Maclaren double-strollers through supermarket aisles -- did not celebrate the home or the homemaker and did not furnish the theoretical tools for us to grapple with our new roles. That women are drawn to traditional modes of parenting is documented in a recent Yankelovich poll that found 87 percent of women believe women are still the main family nurturers, even in two-paycheck families. Not only that, a majority of women, whether working or not, wish they were better parents. We are, many of us, still left high and dry by our political education.

We are torn in a way that is not only theoretical but intensely personal. At the same time that female public achievers earn accolades, many educated and hardworking professional women are unsure they don't long for a life that more closely approximates that of their homemaker mothers. "Having it all" seems to have been a pipe dream. According to a poll conducted in 2000 for Lifetime Television and the Center for Policy Alternatives, 59 percent of women with children under six said they were finding it harder to balance the demands of work and family than they did four years before, and 30 percent said it was "much harder."

My own inner maelstrom centered for a time on the view out my window of my across-the-street neighbor. The mother of three children under the age of seven, she had temporarily forsaken her career as a psychiatric social worker to raise her kids while her husband, a patent lawyer, worked hours that took him away from home from 7 to 7 every day as well as out of town on frequent business trips.

Sitting at my desk, in front of my computer, I watched her unload her groceries from her car in midmorning, two-year-old in tow, and was surprised by the sharp sense of envy I felt. She did the "mindless" chores I'd once been co...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherFree Press

- Publication date2003

- ISBN 10 0684869594

- ISBN 13 9780684869599

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages288

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 3.99

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Made from Scratch: Reclaiming the Pleasures of the American Hearth

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. has a remaider mark. Seller Inventory # 804-4269142705

Made from Scratch: Reclaiming the Pleasures of the American Hearth

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks170404