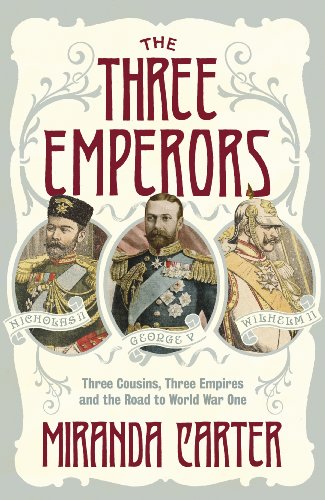

The Three Emperors: Three Cousins, Three Empires and the Road to World War One - Hardcover

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

WILHELM

An Experiment in Perfection

1859

It was a horrible labour. The baby was in the breech position and no one realized until too late. The eighteen-year-old mother had been too embarrassed to allow any of the court physicians to examine or even talk to her about her pregnancy—a prudishness learned from her own mother. The experience of childbirth would cure her of it. To make matters worse, an urgent summons to Berlin’s most eminent obstetrician got lost. After ten or eleven hours of excruciating pain— the mother cried for chloroform, she was given a handkerchief to bite on (her screams, her husband later wrote, were “horrible”)—the attending doctors, one German, one English, had pretty much given up on her and the baby. (There were bad precedents for medics who carried out risky interventions on royal patients: when Princess Charlotte, the heir to the British throne, died in childbirth in 1817, the attending physician felt obliged to shoot himself.) The child survived only because the famous obstetrician eventually received the message and arrived at the last minute. With liberal doses of chloroform and some difficulty, the doctor managed to manipulate the baby out. He emerged pale, limp, one arm around his neck, badly bruised and not breathing. The attending nurse had to rub and slap him repeatedly to make him cry. The sound, when it came, the boy’s father wrote, “cut through me like an electric shock.” Everybody wept with relief. It was 27 January 1859.

At the moment of his birth, two, or arguably three, factors immediately had a defining effect on the life and character of Friedrich Victor Wilhelm Albert Hohenzollern—soon known as Willy to distinguish him, his father said, from the “legion of Fritzes” in the family. Firstly, the baby’s left arm was damaged in the delivery —a fact which, in the relief and excitement following his birth, wasn’t noticed for three days. It seems likely that in the obstetrician’s urgency to get the baby out before he suffocated, he wrenched and irretrievably crushed the network of nerves in Willy’s arm, rendering it useless and unable to grow. Secondly, and unprovably, it’s possible that those first few minutes without oxygen may have caused brain damage. Willy grew up to be hyperactive and emotionally unstable; brain damage sustained at birth was a possible cause.

Thirdly, an almost impossible burden of conflicting demands and expectations came to rest upon Willy at the moment of his birth. Through his father, Friedrich, one of the ubiquitous Fritzes, he was heir to the throne of Prussia; his mother, Vicky, was the first-born child of Queen Victoria of Great Britain, and he was the British queen’s first grandchild. As heir to Prussia, the biggest and most influential power in the loose confederation of thirty-eight duchies, kingdoms and four free cities that called itself Germany, he carried his family’s and country’s dreams of the future. Those dreams saw Prussia as the dominant power in a unified Germany, taking its place as one of the Great Powers. For Queen Victoria, monarch of the richest and arguably most influential country in the world, Willy was both a doted-on grandchild—“a fine fat child with a beautiful soft white skin,” as she put it when she finally saw him twenty months later— and the symbol and vehicle of a new political and dynastic bond between England and Prussia, a state whose future might take it in several different directions, directions in which Britain’s monarch and her husband took an intense interest. Three days after his birth the queen wrote delightedly to her friend and fellow grandmother Augusta of Prussia, “Our mutual grandson binds us and our two countries even closer together!”

Queen Victoria felt a deep affinity with Germany. Her mother was German and so was her husband, Albert, the younger brother of the ruling duke of the small but influential central German duchy of Coburg. She carried on intense correspondences with several German royals, including Fritz’s mother, Augusta, and she would marry six of her nine children to Germans. Although the queen’s Germanophilia was sometimes criticized in England, the British were at least less hostile to the Germans than they were to France and Russia, and occasionally even approving. At the battle of Waterloo, Britain and Prussia had fought side by side to defeat Napoleon, and well into the 1850s as a salute to the old alliance there were still German regiments stationed on the South Coast. Thomas Hardy described the German hussars stationed in Dorset in the 1850s as being so deeply embedded in the local culture that their language had over the years woven itself into the local dialect: “Thou bist” and “Er war” becoming familiar locutions. Germany—or at least the northern part— was the other Protestant power in Europe. German culture was much admired. In turn, German liberals looked to Britain as the model for a future German constitutional monarchy, its traders admired British practice, and at the other end of the political spectrum, it was to England that some of the more reactionary members of the German ruling elite—including Willy’s German grandfather—had fled during the revolutions of 1848. There he and his wife Augusta had become friends— sort of—of the queen and her husband Albert.

Albert, the Prince Consort, an intelligent, energetic and thoughtful man denied a formal public role in England, was even more preoccupied with Germany than his wife, particularly with its future and that of its ruling class. He had seen the German royals rocked by the revolutions of 1848, their very existence called into question by the rise of republicanism and democratic movements. He’d come to believe that Germany’s future lay in unification under a modern liberal constitutional monarchy, like that of England. Prussia, as the largest, strongest state in Germany, was the obvious candidate.

Though it was not necessarily the perfect one. Prussia was a peculiar hybrid, rather like Germany itself: it was half dynamic and forward- looking, half autocratic backwater. On the one hand, it was a rich state with an impressive civil service, a fine education system, and a fast-growing industrial heartland in the Western Rhineland. It had been one of the first states in Europe to emancipate Jews, and had a tradition of active citizenship, demonstrated most visibly in 1813, when it had not been the pusillanimous king but a determined citizenry who had pulled together an army to fight Napoleon. After 1848 a representative assembly, the Landtag, had been forced on the king and liberal politicians and thinkers seemed to be in the ascendant. On the other hand, however, Prussia was stuck in the dark ages: it was a semi- autocracy whose ruling institutions were dominated by a deeply conservative small landowning class from its traditional heartland on the East Elbian plain, the Junkers. They had a reputation for being tough, austere, incorruptible, fearsomely reactionary, piously Protestant, anti-Semitic, feudal in their attitudes to their workers, their land and their women, and resistant to almost any change— whether democratization, urbanization or industrialization—which might threaten their considerable privileges. These included almost total exemption from taxation. They dominated the Prussian court, the most conservative in Germany. They regarded Prussia’s next-door neighbour, Russia—England’s great world rival—as their natural ally, sharing with Russia a long frontier, a belief in autocratic government and a pervasive military culture.

Prussia’s highly professional army was the reason for its domination of Germany, and in many respects gave Prussia what political coherence and identity it had. It had long been dominated by the Junkers, and was the heart of Prussian conservatism. Almost all European aristocracies identified themselves with the army, but since the seventeenth century the Prussian aristocracy, more than any other, had been encouraged by its rulers to equate its noble status and privileges entirely with senior military rank. It was not unusual for boys of the Prussian ruling classes to wear military uniform from the age of six. History showed that war paid: Prussia had benefited territorially from every central European military conflict since the Thirty Years War in the seventeenth century. In the eighteenth century Frederick the Great had doubled Prussia’s size in a series of vicious central European wars. Prussia’s intervention in the Napoleonic Wars had doubled its size again, making it the dominant power in Germany. But at the same time, Prussia’s military culture had arisen not simply from a desire to expand and conquer, but quite as much from the fact that the Prussian ruling class was haunted—obsessed even—by its country’s vulnerability in the middle of Europe, undefended by natural barriers, always a potential victim for some larger power’s territorial ambitions. Territorial expansion had constantly alternated with disaster and near annihilation. During the Thirty Years War, Prussia had lost half its population to disease, famine and fighting; the scar remained in folk memory. During the Napoleonic Wars, it had been humiliated, overrun and threatened with dismemberment while the French and Russians squared up to each other. Since then, Prussia had been hostile to France and carefully deferential to the Russian colossus next door. The ruling dynasties of Hohenzollern and Romanov had intermarried and even developed genuine friendships. Willy’s Prussian great-aunt Charlotte had married Tsar Nicholas I, and Willy’s grandfather, who would become King of Prussia and then Kaiser Wilhelm I of Germany, enjoyed a long and close friendship with his son, Tsar Alexander II.

The contradictions in Prussia mirrored the extraordinary heterogeneity of Germany and its states as a whole. Within its loose boundaries there existed a plethora of conflicting Germanies: the Germany that led the world in scientific and technological innovation, the Germany that was the most cultured, literate, academically innovative state in Europe—the Germany of Goethe, Leibnitz, the von Humboldt brothers, Bach and Beethoven—stood alongside the Germany of resolutely philistine Junkers. In East Elbia, the heartland of the Junker estates, disenfranchised peasants lived in almost feudal conditions, and yet at the same time Germany was the most industrialized place in Europe with some of the best labour conditions. Germany had some of the most hierarchical, undemocratic states in Europe, ruled by an embarrassment of self-important little princelings, and was also home to the largest and best organized Socialist Party in Europe. Southern, predominantly Catholic, Germany coexisted with northern, Protestant Germany. It seems entirely appropriate that Berlin, Prussia’s capital, with its vast avenues, seemed like a parade ground, while also being a centre for political radicalism, for scholarship, for a wealthy Jewish community.

Prince Albert believed there was a battle going on for the soul and political future of Germany. “The German stands in the centre between England and Russia,” he wrote to his future son-in-law Fritz in 1856. “His high culture and his philosophic love of truth drive him towards the English conception, his military discipline, his admiration of the asiatic greatness . . . which is achieved by the merging of the individual into the whole, drives him in the other direction.” Albert also felt that in the post-1848 world, monarchy was under threat. He wanted to prove that good relations between monarchies created peace between countries. And he had come to the conclusion that princes must justify their status by their moral and intellectual superiority to everyone else.

One of Albert’s projects had been to design a rigorous academic regime for his eight children to turn them into accomplished princes. His eldest daughter, Vicky—his favourite—responded brilliantly to it. She was clever, intellectually curious and passionate—qualities not always associated with royalty. Her younger brother Bertie—the future Edward VII—had suffered miserably under the same regime. Albert thought that, under the right circumstances, a royal marriage between Britain and Prussia might nudge Germany in the right direction, towards unification, towards a constitutional monarchy and a safe future for the German royal families. It might even bring about an alliance with Britain, an alliance which could become the cornerstone of peace in Europe. Albert resolved to send his clever daughter on a mission to fix Germany, by marrying Vicky to Friedrich Wilhelm Hohenzollern, nephew of the childless and increasingly doddery King of Prussia, Friedrich Wilhelm IV, and second in line to the throne after his sixty-two-year-old father, who had already taken over many of his brother’s duties.

Fritz, as he was called, was ten years older than Vicky, dashingly handsome, charismatic and an effective officer—so much the Wagnerian hero that in Germany he was actually known as Siegfried. The marriage, which took place in January 1858, looked good on paper—the heir of the rising Protestant German state marrying the daughter of the richest, stablest power in Europe. Unlike most arranged royal marriages, it worked even better in reality. Personally gentle, earnest and prone to depression—somewhat at odds with the emphatically blunt, masculine ideal of the Prussian officer—twenty- seven-year-old Fritz adored his clever seventeen-year-old wife, and she adored him. He also showed, Victoria and Albert noted approvingly, a liking for England and admirable liberal tendencies very much at odds with those of his father and the Prussian court.

At the time, the plan of sending a completely inexperienced seventeen- year-old girl to unify Germany may not have seemed quite so extraordinary as it does now. The external circumstances looked promising. In 1858 the political balance in Prussia seemed to be held by the liberals: they had just won a landslide victory in the Landtag elections. Prussia’s king was elderly and had recently suffered a series of incapacitating strokes, and his heir, Fritz’s father, was sixty-two years old. Fritz and Vicky shouldn’t have to wait too long before they would be in control.

That was the plan. It didn’t turn out that way. Firstly, Albert had been away from Germany a long time and didn’t understand how suspicious the Prussian ruling class was of Vicky’s Englishness, and how touchy about the prospect that larger powers might interfere in its country. “The ‘English’ in it does not please me,” the future chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, told a friend, “the ‘marriage’ may be quite good . . . If the Princess can leave the Englishwoman at home.” Secondly, Vicky, though extremely bright, had no talent for politics, was hopelessly tactless and held fast to her Englishness. Thirdly, Fritz’s father turned out to be astonishingly long-lived, and appointed Otto von Bismarck, the greatest conservative European statesman of the late nineteenth century, his chief minister.

It went wrong quite quickly. The Prussian court was not welcoming and was critical of Vicky’s forthright views and intellectual confidence. Prussian wives were supposed to be silent and submissive; there was none of the leeway allowed in Britain for an intelligent, educated woman to shine. It was said disapprovingly that Vicky dominated Fritz. She met intellectuals and artists, whether or not they were commoners, and this contravened the social strictures of court etiquette: princesses did not host salons or mix with non-royals. Bewildered and isolated, Vicky had no idea what to do. She responded with a social tone-deafness and complete lack of strategic tact which would become characteristic. She complained—imperiously and incessantly—about the philistine, ri...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherLondon: Fig Tree (Penguin Group), 2009.

- Publication date2009

- ISBN 10 0670915564

- ISBN 13 9780670915569

- BindingHardcover

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.25

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Three Emperors: Three Cousins, Three Empires and the Road to World War One

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0670915564

The Three Emperors: Three Cousins, Three Empires and the Road to World War One

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0670915564

The Three Emperors: Three Cousins, Three Empires and the Road to World War One

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0670915564

The Three Emperors: Three Cousins, Three Empires and the Road to World War One

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0670915564

The Three Emperors: Three Cousins, Three Empires and the Road to World War One

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon0670915564

The Three Emperors: Three Cousins, Three Empires and the Road to World War One

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Brand New!. Seller Inventory # VIB0670915564

The Three Emperors: Three Cousins, Three Empires and the Road to World War One CARTER Miranda

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # XCZ-3-128

The Three Emperors: Three Cousins, Three Empires and the Road to World War One

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks150078

The Three Emperors: Three Cousins, Three Empires and the Road to World War One

Book Description Condition: New. Buy with confidence! Book is in new, never-used condition. Seller Inventory # bk0670915564xvz189zvxnew