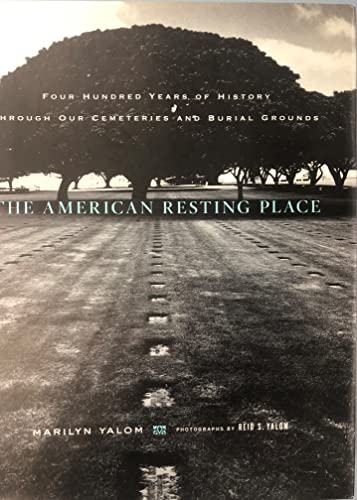

The American Resting Place: 400 Years of History Through Our Cemeteries and Burial Grounds - Hardcover

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Early Spanish Burials When the Spanish explorers arrived in the sixteenth century, they buried their dead as best they could in the wilderness. Hasty disposal of the body, a few ritual words from the Catholic liturgy, no coffin, and a wooden cross were the most one could expect. But with the founding of St. Augustine on the eastern coast of Florida in 1565 and the establishment of a colony in New Mexico in 1598, the Spanish began to build Catholic churches with adjacent churchyards. According to an oral narrative passed down from one generation to the next in a New Mexican village and recorded in 1933, this is how the burials took place: In the olden days the church was used for a graveyard and the planks were removed while the grave was dug. The body was wrapped in a rug and lowered into the grave, which was filled and the boards replaced. This custom prevailed until the entire space was filled with the dead. Prominent Catholics would be placed under the floor close to thhe altar, but as no records were kept of the location and no markers set into the floor, it is impossible to know exactly where a speeeeecific individual lay. When the space under the church was filled, bodies were interred outside the church in an area known as the campo santo — the sacred field. In the Southwest, the campo santo became the final resting place for generations of converted Indians, whereas members of the Spanish community continued to be buried under the church.

Jamestown, Virginia Hard on the heels of the Hispanic Catholics, English Protestants found their way to the Americas in the early seventeenth century, and they, like the Spaniards, were quickly faced with the task of burying their dead in foreign soil. Most of the English settlers who founded Jamestown in the spring of 1607 were dead by the end of summer; of the original 104, only thirty-eight remained alive the following January. One of them noted: “Our men were destroyed with cruell diseases, as Swellings, Flixes, Burning Fevers, and by warres, . . . but for the most part they died of meere famine.” Those who survived were, in the words of Captain John Smith, “scarce able to bury the dead.” Where were all these dead buried? Extensive archaeological work undertaken at Jamestown since 1994 has unearthed the remains of numerous bodies within the confines of the fort, buried there behind the palisade at night in an attempt to conceal the settlers’ losses from the surrounding Indians. Twenty-two of the graves are now marked with wooden crosses. Most of the corpses were placed in the ground without coffins, many wrapped in shrouds, and a few buried fully clothed — probably because these had died of contagious diseases. A larger, more substantial cross marks the spot where a single coffin — gable-lidded in the style of the affluent — was discovered just outside the fort palisade (plate 2). There is good reason to believe that the skeleton it contained is that of Bartholomew Gosnold, captain of the Godspeed, one of the first three ships sent to Jamestown by the Virginia Company. The Godspeed and the other vessels arrived in May after a grueling five-month voyage; Gosnold was dead by August, at the age of thirty- six — the same age determined for the skeleton at the time it was interred. Written records indicate that Gosnold’s burial was accompanied by many volleys of gunshot. A second piece of evidence for identification of the skeleton was the five-foot iron-tipped staff that had been laid on top of the coffin. This ceremonial weapon would have belonged to the captain of a company, to be used while leading his men through military exercises. Bartholomew Gosnold was an experienced captain, respected not only for his participation in the Jamestown enterprise but also for his previous expeditions on the northeast coast, where he had discovered the islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Elisabeth Island, named for his daughters. A large cross has been erected at his burial site, but his skeleton now reclines in the nearby museum. If we are to judge from the size of his skeleton and the soundness of his teeth, he must have been a strapping fellow. During its first two years, under the leadership of Captain John Smith and with help from the Powhatan Indians, the colony survived — but just barely. Only ninety of nearly three hundred colonists made it through the “starving time,” the winter of 1609 and 1610. The by-now-famous story of the Indian princess Pocahontas, who reputedly saved the life of John Smith and definitely married the tobacco planter John Rolfe, contributed to a long period of peace between the English and the Powhatans. But eventually, in 1622, members of the Powhatan chiefdom attacked the English and killed off a third of the population. By then, the settlement had an Anglican frame church and a proper English-type churchyard, both situated on one side of the fort. Today’s visitor will find the remains of a later brick church, a church tower dating from the 1640s, and twenty-five tombstones from an estimated several hundred burials in the churchyard. Tombstones were uncommon throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in tidewater Virginia, since the area had very little natural stone, and headstones had to be imported, usually from England. Most people were laid to rest in unmarked graves or in graves with wooden markers that quickly disintegrated. In addition to the churchyard burials, some parishioners of high status were buried within or underneath the church. Excavations conducted in the early twentieth century revealed at least twenty burials within the church chancel, including two marked graves, one the tomb of a British knight and the other the tomb of a minister. It is a rare sensation to stand beside the church ruins on the banks of the James River and imagine yourself as one of the 104 men and boys who first came ashore in the spring of 1607 to claim the fertile lands they called Virginia; or as one of the first slaves whose forced passage from Africa to Jamestown in 1619 was the beginning of unspeakable suffering and dehumanization; or as one of the ninety unmarried women who arrived in 1620, ready to marry any man who would pay her unpaid passage. Or, reversing one’s viewpoint, imagine the emotions of the Powhatans watching from a distance as strange fair-skinned people encamped upon territory that had belonged to their tribe. Did they feel in their bones that those pale-faced strangers would eventually dispossess them of their land and their entire way of life?

Plymouth, Massachusetts The settlers who arrived at Plymouth, Massachusetts, on the Mayflower in December 1620 — like those in Jamestown thirteen years earlier—were immediately assailed by overwhelming hardships. In the words of William Bradford, “In two or three months half of their company died, especially in January and February being the depth of winter. . . .” Bradford attributed their deaths specifically to “the scurvy and other diseases which this long voyage and lack of accommodation had brought upon them.” Though fifty-two of the original 102 settlers survived the winter, only “six or seven sound persons” were fully functional at the times of greatest distress. Among those healthy enough to help were the Puritan elder William Brewster and the military captain Miles Standish; Bradford praised their ministrations, noting that they cared for the sick and dying and “spared no pains night nor day but with abundance of toil and hazard of their own health, fetched them wood, made them fires, dressed them meat, made their beds, washed their loathsome clothes, clothed and unclothed them; in a word did all the homely and necessary offices for them which dainty and queasy stomachs cannot endure to hear named.” One of their most onerous duties was to bury the dead. The first burial site, eventually named Cole’s Hill, was used until around 1637; thereafter, Burial Hill, with the colonial tombstones still there today, became the principal Pilgrim burying ground. A sarcophagus commissioned by the Society of Mayflower Descendants contains the bones of Pilgrims found in or near Cole’s Hill. A part of its inscription reads: “The Monument marks the First Burying Ground in Plymouth of the passengers of the Mayflower. Here under cover of darkness the fast dwindling company laid their dead, leveling the earth above them lest the Indians should know how many were the graves.” As in Jamestown, it seems to have been common practice in Plymouth for the settlers to perform burials at night. They did such a good job in hiding the dead that some of the bones on Cole’s Hill were not uncovered until more than a hundred years later during a violent rainstorm. Yet when their first governor, John Carver, died, in the spring of 1621, the Pilgrims laid him to rest with public ceremony befitting his station, including volleys of gunshot.

Native American and Christian Burial Practices Christians brought from Europe their manner of burial, but Native Americans had their own practices, which European settlers observed with curiosity. Upon their arrival at Plymouth, a Pilgrim scouting party came across a gravesite consisting of sand mounds covered with decaying reed mats. The Pilgrims poked into the mounds and, in one of them, found a bow with several rotting arrows. As narrated by William Bradford and Edward Winslow, “We supposed there were many other things, but because we deemed them graves, we put in the Bow againe and made it up as it was, and left the rest untouched, because we thought it would be odious unto them to ransacke their Sepulchers.” Continuing their exploration, the scouting party came upon other gravesites, including “a great burying place, one part whereof was incompassed with a large Palazado, like a churchyard . . . those Graves were more sumptuous then those at Corne-hill, yet we digged none of them up, but only viewed them, and went our way.” Despite their curiosity and some grave pilfering when they first arrived, the Pilgrims tended to respect the sanctity of Indian graves. Later in the seventeenth century, William Penn wrote sympathetically of Indian burial rites practiced in Pennsylvania.

If they die, they bury them with their apparel, be they man or woman, and the nearest of kin fling in something precious with them, as a token of their love: their mourning is blacking of their faces, which they continue for a year. . . .

As for their graves, “lest they should be lost by time, and fall to common use, they pick off the grass that grows upon them, and heap up the fallen earth with great care and exactness.” In time, this practice spread beyond the Indian community. Scraped mounds stripped of grass and other vegetation, usually located on hilltops, became characteristic of nineteenth- century folk cemeteries in Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, and Texas, for whites as well as Indians. This is a rare instance of Native American influence on Christian burial practices. Usually the influence went the other way. American Indians confronting European settlers struggled to maintain their age-old burial rites. Yet ultimately, as Europeans invaded and conquered what had been tribal territories, a great number of Indians came to be buried in Christian graveyards. Both Spanish missionaries in the Southwest and Protestant ministers throughout the continent took pride in the conversion of Indians and considered churchyard burial the convert’s due. Christian interment was understood as the final step on the path toward God. One of the most interesting examples of how indigenous peoples merged their burial rites with those of Christian newcomers can be seen in Eklutna, Alaska. There, in keeping with old traditions, Athabascan natives still bury the dead in small mounds surrounded by stones with spirit houses placed on top of them. These miniature houses, three to four feet long and two to three feet high, have no markings other than colorful decorations — squares, circles, and triangles painted red, yellow, and blue — that denote the deceased person’s family, like a coat of arms. Around the turn of the eighteenth century, Catherine the Great sent Russian missionaries to northern Alaska...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherHoughton Mifflin Harcourt

- Publication date2008

- ISBN 10 0618624279

- ISBN 13 9780618624270

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages336

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.25

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The American Resting Place: 400 Years of History Through Our Cemeteries and Burial Grounds

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Prompt service guaranteed. Seller Inventory # Clean0618624279

The American Resting Place: 400 Years of History Through Our Cemeteries and Burial Grounds

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0618624279

The American Resting Place: 400 Years of History Through Our Cemeteries and Burial Grounds

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0618624279

The American Resting Place: 400 Years of History Through Our Cemeteries and Burial Grounds

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon0618624279

The American Resting Place: 400 Years of History Through Our Cemeteries and Burial Grounds

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # newMercantile_0618624279

The American Resting Place: 400 Years of History Through Our Cemeteries and Burial Grounds

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0618624279

The American Resting Place: 400 Years of History Through Our Cemeteries and Burial Grounds

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new0618624279

The American Resting Place: 400 Years of History Through Our Cemeteries and Burial Grounds

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0618624279

The American Resting Place: 400 Years of History Through Our Cemeteries and Burial Grounds

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. 1.7. Seller Inventory # 0618624279-2-1

The American Resting Place: 400 Years of History Through Our Cemeteries and Burial Grounds

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Brand New!. Seller Inventory # VIB0618624279