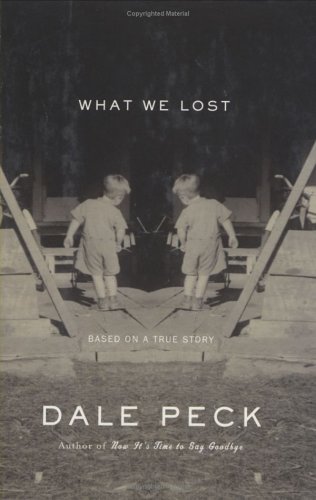

What We Lost - Hardcover

The critically acclaimed author of Now It's Time to Say Goodbye offers a thoughful biography of his father's tumultuous childhood and youth, describing his childhood in a poverty-stricken Long Island home with an abusive mother and alcoholic father, his move to his uncle's farm in upstate New York, and his difficult choice between his broken family and his future.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

Winner of a Guggenheim Fellowship, Peck started writing fiction as a freshman at Drew, but really blossomed as a writer in his junior and senior years. He worked closely with several professors in the Drew English department to hone a writing style that would earn him the department's highest honor for his unpublished first novel, All the World, which was his senior honors thesis.

All three of Peck's published novels reflect his love of stories and story-telling. Martin and John recounts a gay man's coming of age; The Law of Enclosures, recently made into a movie, shifts the focus to John's parents; and Now It's Time to Say Goodbye places characters from the first two novels on a larger stage, prompting the Los Angeles Times to write that Peck is "one of the few avant-garde writers of any age who is changing the rules for prose fiction." Peck also teaches writing, and does book reviews for publications such as the Village Voice Literary Supplement, London Review of Books, and the New York Times Book Review.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

All three of Peck's published novels reflect his love of stories and story-telling. Martin and John recounts a gay man's coming of age; The Law of Enclosures, recently made into a movie, shifts the focus to John's parents; and Now It's Time to Say Goodbye places characters from the first two novels on a larger stage, prompting the Los Angeles Times to write that Peck is "one of the few avant-garde writers of any age who is changing the rules for prose fiction." Peck also teaches writing, and does book reviews for publications such as the Village Voice Literary Supplement, London Review of Books, and the New York Times Book Review.

1

The old man has an odor like a force field. He wakes the boy before dawn.

Quiet, he says, and underneath his black coat his kitchen whites reek of

cabbage, stewed meat, spoiled milk. We don"t want to get your mother up.

The old man"s clothes stink of institutional food but it is his

breath, wet and sickly sweet, that leaves a weight on the boy"s cheek like his

sisters" hairspray when they shoo him from the bathroom. Reluctantly he

edges out of bed. Like the old man, he wears his work clothes, jeans,

undershirt, brown corduroy jacket—everything but shoes. He shivers in his

socks and watches in the half light as the pillowcase is stripped from his

pillow and filled with clothes from the dresser, trying to warm his thin chest

with thin arms and the thinner sleeves of his jacket.

That"s Jimmy"s shirt.

The old man claps him in the stomach with a pair of boots.

You shut up and put these on.

The boots are cold and damp and pinch the boy"s feet as he

squeezes into them, and as he knots the laces he watches Lance"s drawers

and Jimmy"s football jersey disappear into the pillowcase.

But Dad.

Sshh!

The old man stuffs a pair of jeans into the sack.

But Dad. Those are Duke"s.

The old man looks at the shock of blond hair on the far side of the

bed, and when he turns to the boy the empty bottles in his pockets rattle and

the boy can smell what was in them too.

You won"t have to worry about that bastard no more, the old man

says, breath lighting up the air like sparked acetylene. Not where you"re

going.

If any of the boys has awakened he gives no sign. Already Lance

is hugging the extra inches of blanket where the boy had lain, and Jimmy,

slotted into the crease between the pushed-together mattresses, seems

folded along his spine like a blade of grass. At the far end of the bed Duke

lies with his back to his dark-haired brothers, the stiff collar of his

houndstooth coat sticking out beyond the blanket. A few inches beyond

Duke"s nose the rope-hung sheet dividing the boys" bed from their sisters"

puckers in a draft, but Duke never goes to sleep without making sure the

holes on the girls" half of the curtain are covered by solid patches on the

boys", and so the boy can catch no glimpse of Lois or Edi or Joanie as he is

surfed out of the room by the old man"s frozen spittle. All he glimpses in the

gap between curtain and floor is a banana peel and two apple cores, and his

stomach rumbles and he wants to check his jacket to see if his siblings have

left him any food. But the old man is nudging him, Faster, faster, and the boy

has to use both hands to descend the ladder"s steep rungs. Down below, the

quilts fencing off his parents" bed are drawn tight as tent flaps, and although

his mother"s snores vibrate through tattered layers of cotton batting both she

and the baby, Gregory, tucked in his crib beside her, remain invisible.

The boy pauses at the stovepipe and its single coal of heat in the

hopes of warming his stiff boots, but the old man steps on his heels.

Hurry it up, he whispers, clouting him on the back of the head with

the sack. Unless you feel the need for a goodbye kiss from your ma.

Outside the air is cold and wet and, low down—down around his

knees—gauzy with dawn vapors, and underneath the vapors the frozen grass

breaks beneath the boy"s boots with a sound like ice chewed behind closed

lips. His ice-cold boots mash his toes, but it"s not until they"ve walked

through their yard and the Slovak"s that a space opens up between two

ribbons of mist and the boy sees that the boots are pinching his feet not

because they"re cold or wet but because the old man has handed him

Jimmy"s instead of his own. They had been the boy"s, up until about three

months ago, but even though Jimmy is two years older and two inches taller

than the boy, his feet have been a size smaller than the boy"s since he was

eight years old, and just before Thanksgiving the boy had traded Jimmy his

shoes for the pants he"s wearing now. The pants are a little long on him, a

little loose in the waist, the outgrown boots squeeze his feet like a huckster"s

handshake. But when he turns back toward the house there is the old man,

hissing,

C"mon, c"mon, hurry it up. It"s late enough already.

All around them the dark round shapes of their neighbors" cars

loom out of the fog like low-tide boulders, and down at the end of the block

the cab of the old man"s flatbed truck rises above them, a breaching whale.

The cab is white, or was white; it"s barnacled with flecked rust now, a lacy

caul of condensation veils the windscreen. The boy stares at the soft-skull

shape of it as he minces down the block, not quite understanding why the

sight is confusing, unsettling even. Then:

Hey Dad. Why"d you park all the way—

The old man cuts him off with another Sshh! and then, when the

driver"s side door breaks open from the cab with the same sound the shade

tree made when it fell in front of the garage three winters ago, the boy

suddenly realizes how quiet their street is, and the streets beyond theirs.

Seat springs creak and whine like the grade school orchestra as the old man

settles into the cab, the pillowcase rustles audibly as the boy takes it from

him and drops it to his lap. Then glass clinks as the old man opens his coat

and pulls what looks like an empty bottle from a pocket in the lining, and

when he arches his head back to suck whatever imagined vapor lingers in the

brown glass the sound that comes from his loose dentures is the same

sound that Gregory makes when his mother puts a bottle to his toothless

lips. And all of these noises are as familiar to the boy as the thinning strands

of the old man"s hair, his winter-burned scalp, the globe of bone beneath the

skin, but just as the half light shadows the old man"s features, deepening and

obscuring them, the morning hush seems to amplify the noises in the cab,

giving them the ominous sharpness of a movie soundtrack. And there is a

hardness to the old man"s eyes as well, slitted into the ravines of his slack

stubbled cheeks, a glint Duke once said always came about nine months

before another baby. The boy can"t remember if Duke had said that before or

after the old man whipped him.

The old man throws the empty bottle with the others at the boy"s

feet and straightens behind the wheel. His left and right hands work choke

and key with the resigned rhythm of a chain gang, and after three rounds the

engine turns over once, twice, then chugs into life with a lifelong smoker"s

cough, and the boy remembers something else Duke had said about the old

man. The old man, Duke said, used to smoke like everyone else, but he gave

it up when one time his breath was so strong his burps caught fire, and he

pointed to the charred leather above the driver"s seat as proof. Sitting in the

cab now, it is easy to believe Duke"s story. Everything about the truck is

animated as a carnival, from the trampolining seat to the pneumatic sigh of

the clutch to the spindly stick of the gearshift, which the old man

manipulates as though it were a cross between a magic wand and a knob-

headed cane. Down around the boy"s throbbing feet the glass bottles tinkle

their accompaniment and up above are the old man"s fiercely focused eyes,

and the boy is so distracted by all this drama that he nearly forgets to take a

last look at his house. By the time he turns all he sees are the empty panes

of glass in the garage door that the shade tree smashed when it fell. The

black rectangles gape like lost teeth amid the frosted white panes, like pages

ripped from a book or tombstones stolen from a graveyard, and for some

reason the sight of them fills the boy with a sense of loss and dread. Then

there is just the shade tree, dead now, leafless and twigless but otherwise

intact, and still blocking the garage door as it has for the past three years.

Brentwood, Long Island, 1956. The most important local industry

might not be the Entenmann"s factory but it is to a boy of twelve, almost

thirteen, and as the truck rattles down Fifth Avenue the boy cracks open the

triangular front window in his door and presses his nose to it as he always

does. It is too cold and the factory is six blocks away and the boy can smell

little more than a ghost of sugar on the wet air, but in his mind the street is

doughy as a country kitchen, and as he inhales he pretends he can sort the

different odors of crumb and glazed and chocolate-covered donuts from an

imaginary baker"s hash of heat and wheat and yeast. The sharp vanilla edge

of angel food cake or the cherry tinge of frosted Danish or his favorite, the soft

almost wet odor of all-butter French loaf. He likes it for the name even more

than the taste—a loaf they call it, like bread, when it is sweeter than any

cake. In fact he has eaten it so few times the taste is a memory trapped in

his head in a space apart from his tongue, but whenever he stocks the

pastries section of Slaussen"s Market his nostrils .are as if they can smell

the brick-sized loaves through waxed cardboard and cellophane.

It"s when they pass Slaussen"s that the boy realizes they"re

headed for the Southern State. Big white signs fill the store"s dark windows.

PORK CHOPS 19¢/LB! IDAHO POTATOES, PERFECT FOR BAKING!

ORDER YOUR XMAS TURKEY NOW! The boy turns his head to stare at this

last notice as they drive by. It"s the second week of January and the

disjunction tickles his mind, but only faintly, like the flavor of all-butter French

loaf. But then he remembers something else.

Will I be back for work?

The way the old man operates the truck reminds the boy of a

puppet show. He is all elbows and knees, jerks and lunges and rapid glances

to left and right, and he doesn"t spare an eye for the boy when he answers

him.

Close your window, he says. And then: What time do you clock

in?

I go in after school.

The old man turns right onto Spur Drive North without slowing,

drops the truck into second in an attempt to maintain speed up the on-ramp.

The tires squeal around the corner and the truck bucks as though running

over a body when the old man downshifts, and then the ancient engine hauls

the truck up the incline like a man pulling a sled by a rope.

What time do you clock in?

The boy doesn"t answer. Instead he watches the road, not afraid,

only mildly curious, as the truck slides across both lanes of the parkway and

drops two tires into the center median before the old man steadies its

course. The old man has gone into the median so many times that the older

boys refer to the strip of grass as the Lloyd Parkway, and one time,

according to Duke, the old man went all the way over to the eastbound lane

and was halfway to work before he realized it. Now he continues half-on and

half-off the road for another quarter mile before jerking the truck back into the

left lane.

Did you close your window?

The boy looks up. The old man is using the end of his sleeve to

rub something, dust or frost, off a gauge on the dash, and when he"s finished

he squints at the gauge and then he says, You won"t be going into

Slaussen"s tonight. He looks down at the boy and lets the big wheel go slack

in his hands. Where you"re going you"ll wish sacks of potatoes was all you

had to haul around. Shit, boy, he says, that"s what you"ll be carting soon.

Wheelbarrels full of—

The crunch of median gravel under the left front tire brings his

attention back to the road. The steering wheel is as big as a pizza and twirls

like one too, as the old man wrestles the truck onto the roadway.

Did you close your window?

The boy ignores him. The truck"s heater has been broken since

before he can remember and it will make no difference if the vent window is

open or closed. If they drive long enough the engine"s heat might pulse

through the dash and if it does he will close the window, but at this point,

despite the sack of clothes he has buried his hands in for warmth, he doesn"t

believe they will be on the road very long. And besides, the pillowcase is tiny,

almost empty. Only one change of clothes, even if none of them fit him. But

at least they won"t hurt him, like Jimmy"s shoes.

Already the fog has thinned, skulking in the median as if afraid of

the big truck, but no other cars are on the road; and as they drive the pain in

the boy"s feet changes. The sharp pinching in his toes dissipates slightly,

becomes a general ache he feels throughout his feet, less strong but more

pervasive, and he is trying to decide if this is more or less bearable than the

initial pinching when the old man veers toward the exit for Dix Hills.

The boy relaxes then. Even though he doesn"t know the names of

these streets he knows the rhythms of the starts and stops and turns

through them, can feel the rightness or wrongness of the truck"s movement in

his belly—indeed, he"s been feeling it since his time in his mother"s. Both his

parents are employed at Pilgrim State Mental Hospital, and before the boy

started school he stayed at the enormous hospital"s daycare facility, which

he remembers as a place of lights so bright he could never find Jimmy and

his sisters—Duke was already in school by then, and Lance wasn"t born until

after the boy started going to Brentwood Elementary. Then, not long after he

left daycare, the boy"s mother began sending him with the old man when he

went to pick up his paycheck Friday afternoons, because most of the bars

the old man frequents won"t let him bring the boy in with him and, during the

winter at least, the old man doesn"t make the boy sit out in the truck for more

than a half hour or two. And even though it is Saturday morning and the old

man should have collected his paycheck yesterday, the boy isn"t all that

troubled. He simply assumes they"re en route to another of the old man"s

errands: helping the hospital"s dairyman unload crates of eggs onto the back

of their truck, or taking out the kitchen trash, which just happens to contain a

couple gunnysacks of potatoes or waxed cardboard boxes of broccoli still

tightly packed in ice. He ignores the pillowcase in his hands, the glint in the

old man"s eyes. The old man is twitchy but repetitive, he reminds himself—a

broken record, Duke calls him, stuck in a groove. If his actions sometimes

appear random, it is only the contained chaos of one marble clicking off

another in the schoolyard, willy-nilly inside the tiny chalk circle but easily

predictable within the broad scheme of things. Eventually everything will

become clear, if not immediately then at some not-too-distant point.

The looming crooked edifice of the hospital is just visible in the

distance when the old man eases the truck down a dark narrow alleyway,

seemingly forgetting to brake until the nose of the truck is inches from the

sooty bricks of the alley"s terminal wall. Now the boy understands what"s

going on. This is the Jew"s back door, and the old man comes here with

almost the same regularity as he goes to the payroll office at the hospital a

mile down the road. The boy only takes the time to loosen the laces on his

boots before pressing his ear to the open window—his left ear, so he can turn

and face the scene taking pl...

The old man has an odor like a force field. He wakes the boy before dawn.

Quiet, he says, and underneath his black coat his kitchen whites reek of

cabbage, stewed meat, spoiled milk. We don"t want to get your mother up.

The old man"s clothes stink of institutional food but it is his

breath, wet and sickly sweet, that leaves a weight on the boy"s cheek like his

sisters" hairspray when they shoo him from the bathroom. Reluctantly he

edges out of bed. Like the old man, he wears his work clothes, jeans,

undershirt, brown corduroy jacket—everything but shoes. He shivers in his

socks and watches in the half light as the pillowcase is stripped from his

pillow and filled with clothes from the dresser, trying to warm his thin chest

with thin arms and the thinner sleeves of his jacket.

That"s Jimmy"s shirt.

The old man claps him in the stomach with a pair of boots.

You shut up and put these on.

The boots are cold and damp and pinch the boy"s feet as he

squeezes into them, and as he knots the laces he watches Lance"s drawers

and Jimmy"s football jersey disappear into the pillowcase.

But Dad.

Sshh!

The old man stuffs a pair of jeans into the sack.

But Dad. Those are Duke"s.

The old man looks at the shock of blond hair on the far side of the

bed, and when he turns to the boy the empty bottles in his pockets rattle and

the boy can smell what was in them too.

You won"t have to worry about that bastard no more, the old man

says, breath lighting up the air like sparked acetylene. Not where you"re

going.

If any of the boys has awakened he gives no sign. Already Lance

is hugging the extra inches of blanket where the boy had lain, and Jimmy,

slotted into the crease between the pushed-together mattresses, seems

folded along his spine like a blade of grass. At the far end of the bed Duke

lies with his back to his dark-haired brothers, the stiff collar of his

houndstooth coat sticking out beyond the blanket. A few inches beyond

Duke"s nose the rope-hung sheet dividing the boys" bed from their sisters"

puckers in a draft, but Duke never goes to sleep without making sure the

holes on the girls" half of the curtain are covered by solid patches on the

boys", and so the boy can catch no glimpse of Lois or Edi or Joanie as he is

surfed out of the room by the old man"s frozen spittle. All he glimpses in the

gap between curtain and floor is a banana peel and two apple cores, and his

stomach rumbles and he wants to check his jacket to see if his siblings have

left him any food. But the old man is nudging him, Faster, faster, and the boy

has to use both hands to descend the ladder"s steep rungs. Down below, the

quilts fencing off his parents" bed are drawn tight as tent flaps, and although

his mother"s snores vibrate through tattered layers of cotton batting both she

and the baby, Gregory, tucked in his crib beside her, remain invisible.

The boy pauses at the stovepipe and its single coal of heat in the

hopes of warming his stiff boots, but the old man steps on his heels.

Hurry it up, he whispers, clouting him on the back of the head with

the sack. Unless you feel the need for a goodbye kiss from your ma.

Outside the air is cold and wet and, low down—down around his

knees—gauzy with dawn vapors, and underneath the vapors the frozen grass

breaks beneath the boy"s boots with a sound like ice chewed behind closed

lips. His ice-cold boots mash his toes, but it"s not until they"ve walked

through their yard and the Slovak"s that a space opens up between two

ribbons of mist and the boy sees that the boots are pinching his feet not

because they"re cold or wet but because the old man has handed him

Jimmy"s instead of his own. They had been the boy"s, up until about three

months ago, but even though Jimmy is two years older and two inches taller

than the boy, his feet have been a size smaller than the boy"s since he was

eight years old, and just before Thanksgiving the boy had traded Jimmy his

shoes for the pants he"s wearing now. The pants are a little long on him, a

little loose in the waist, the outgrown boots squeeze his feet like a huckster"s

handshake. But when he turns back toward the house there is the old man,

hissing,

C"mon, c"mon, hurry it up. It"s late enough already.

All around them the dark round shapes of their neighbors" cars

loom out of the fog like low-tide boulders, and down at the end of the block

the cab of the old man"s flatbed truck rises above them, a breaching whale.

The cab is white, or was white; it"s barnacled with flecked rust now, a lacy

caul of condensation veils the windscreen. The boy stares at the soft-skull

shape of it as he minces down the block, not quite understanding why the

sight is confusing, unsettling even. Then:

Hey Dad. Why"d you park all the way—

The old man cuts him off with another Sshh! and then, when the

driver"s side door breaks open from the cab with the same sound the shade

tree made when it fell in front of the garage three winters ago, the boy

suddenly realizes how quiet their street is, and the streets beyond theirs.

Seat springs creak and whine like the grade school orchestra as the old man

settles into the cab, the pillowcase rustles audibly as the boy takes it from

him and drops it to his lap. Then glass clinks as the old man opens his coat

and pulls what looks like an empty bottle from a pocket in the lining, and

when he arches his head back to suck whatever imagined vapor lingers in the

brown glass the sound that comes from his loose dentures is the same

sound that Gregory makes when his mother puts a bottle to his toothless

lips. And all of these noises are as familiar to the boy as the thinning strands

of the old man"s hair, his winter-burned scalp, the globe of bone beneath the

skin, but just as the half light shadows the old man"s features, deepening and

obscuring them, the morning hush seems to amplify the noises in the cab,

giving them the ominous sharpness of a movie soundtrack. And there is a

hardness to the old man"s eyes as well, slitted into the ravines of his slack

stubbled cheeks, a glint Duke once said always came about nine months

before another baby. The boy can"t remember if Duke had said that before or

after the old man whipped him.

The old man throws the empty bottle with the others at the boy"s

feet and straightens behind the wheel. His left and right hands work choke

and key with the resigned rhythm of a chain gang, and after three rounds the

engine turns over once, twice, then chugs into life with a lifelong smoker"s

cough, and the boy remembers something else Duke had said about the old

man. The old man, Duke said, used to smoke like everyone else, but he gave

it up when one time his breath was so strong his burps caught fire, and he

pointed to the charred leather above the driver"s seat as proof. Sitting in the

cab now, it is easy to believe Duke"s story. Everything about the truck is

animated as a carnival, from the trampolining seat to the pneumatic sigh of

the clutch to the spindly stick of the gearshift, which the old man

manipulates as though it were a cross between a magic wand and a knob-

headed cane. Down around the boy"s throbbing feet the glass bottles tinkle

their accompaniment and up above are the old man"s fiercely focused eyes,

and the boy is so distracted by all this drama that he nearly forgets to take a

last look at his house. By the time he turns all he sees are the empty panes

of glass in the garage door that the shade tree smashed when it fell. The

black rectangles gape like lost teeth amid the frosted white panes, like pages

ripped from a book or tombstones stolen from a graveyard, and for some

reason the sight of them fills the boy with a sense of loss and dread. Then

there is just the shade tree, dead now, leafless and twigless but otherwise

intact, and still blocking the garage door as it has for the past three years.

Brentwood, Long Island, 1956. The most important local industry

might not be the Entenmann"s factory but it is to a boy of twelve, almost

thirteen, and as the truck rattles down Fifth Avenue the boy cracks open the

triangular front window in his door and presses his nose to it as he always

does. It is too cold and the factory is six blocks away and the boy can smell

little more than a ghost of sugar on the wet air, but in his mind the street is

doughy as a country kitchen, and as he inhales he pretends he can sort the

different odors of crumb and glazed and chocolate-covered donuts from an

imaginary baker"s hash of heat and wheat and yeast. The sharp vanilla edge

of angel food cake or the cherry tinge of frosted Danish or his favorite, the soft

almost wet odor of all-butter French loaf. He likes it for the name even more

than the taste—a loaf they call it, like bread, when it is sweeter than any

cake. In fact he has eaten it so few times the taste is a memory trapped in

his head in a space apart from his tongue, but whenever he stocks the

pastries section of Slaussen"s Market his nostrils .are as if they can smell

the brick-sized loaves through waxed cardboard and cellophane.

It"s when they pass Slaussen"s that the boy realizes they"re

headed for the Southern State. Big white signs fill the store"s dark windows.

PORK CHOPS 19¢/LB! IDAHO POTATOES, PERFECT FOR BAKING!

ORDER YOUR XMAS TURKEY NOW! The boy turns his head to stare at this

last notice as they drive by. It"s the second week of January and the

disjunction tickles his mind, but only faintly, like the flavor of all-butter French

loaf. But then he remembers something else.

Will I be back for work?

The way the old man operates the truck reminds the boy of a

puppet show. He is all elbows and knees, jerks and lunges and rapid glances

to left and right, and he doesn"t spare an eye for the boy when he answers

him.

Close your window, he says. And then: What time do you clock

in?

I go in after school.

The old man turns right onto Spur Drive North without slowing,

drops the truck into second in an attempt to maintain speed up the on-ramp.

The tires squeal around the corner and the truck bucks as though running

over a body when the old man downshifts, and then the ancient engine hauls

the truck up the incline like a man pulling a sled by a rope.

What time do you clock in?

The boy doesn"t answer. Instead he watches the road, not afraid,

only mildly curious, as the truck slides across both lanes of the parkway and

drops two tires into the center median before the old man steadies its

course. The old man has gone into the median so many times that the older

boys refer to the strip of grass as the Lloyd Parkway, and one time,

according to Duke, the old man went all the way over to the eastbound lane

and was halfway to work before he realized it. Now he continues half-on and

half-off the road for another quarter mile before jerking the truck back into the

left lane.

Did you close your window?

The boy looks up. The old man is using the end of his sleeve to

rub something, dust or frost, off a gauge on the dash, and when he"s finished

he squints at the gauge and then he says, You won"t be going into

Slaussen"s tonight. He looks down at the boy and lets the big wheel go slack

in his hands. Where you"re going you"ll wish sacks of potatoes was all you

had to haul around. Shit, boy, he says, that"s what you"ll be carting soon.

Wheelbarrels full of—

The crunch of median gravel under the left front tire brings his

attention back to the road. The steering wheel is as big as a pizza and twirls

like one too, as the old man wrestles the truck onto the roadway.

Did you close your window?

The boy ignores him. The truck"s heater has been broken since

before he can remember and it will make no difference if the vent window is

open or closed. If they drive long enough the engine"s heat might pulse

through the dash and if it does he will close the window, but at this point,

despite the sack of clothes he has buried his hands in for warmth, he doesn"t

believe they will be on the road very long. And besides, the pillowcase is tiny,

almost empty. Only one change of clothes, even if none of them fit him. But

at least they won"t hurt him, like Jimmy"s shoes.

Already the fog has thinned, skulking in the median as if afraid of

the big truck, but no other cars are on the road; and as they drive the pain in

the boy"s feet changes. The sharp pinching in his toes dissipates slightly,

becomes a general ache he feels throughout his feet, less strong but more

pervasive, and he is trying to decide if this is more or less bearable than the

initial pinching when the old man veers toward the exit for Dix Hills.

The boy relaxes then. Even though he doesn"t know the names of

these streets he knows the rhythms of the starts and stops and turns

through them, can feel the rightness or wrongness of the truck"s movement in

his belly—indeed, he"s been feeling it since his time in his mother"s. Both his

parents are employed at Pilgrim State Mental Hospital, and before the boy

started school he stayed at the enormous hospital"s daycare facility, which

he remembers as a place of lights so bright he could never find Jimmy and

his sisters—Duke was already in school by then, and Lance wasn"t born until

after the boy started going to Brentwood Elementary. Then, not long after he

left daycare, the boy"s mother began sending him with the old man when he

went to pick up his paycheck Friday afternoons, because most of the bars

the old man frequents won"t let him bring the boy in with him and, during the

winter at least, the old man doesn"t make the boy sit out in the truck for more

than a half hour or two. And even though it is Saturday morning and the old

man should have collected his paycheck yesterday, the boy isn"t all that

troubled. He simply assumes they"re en route to another of the old man"s

errands: helping the hospital"s dairyman unload crates of eggs onto the back

of their truck, or taking out the kitchen trash, which just happens to contain a

couple gunnysacks of potatoes or waxed cardboard boxes of broccoli still

tightly packed in ice. He ignores the pillowcase in his hands, the glint in the

old man"s eyes. The old man is twitchy but repetitive, he reminds himself—a

broken record, Duke calls him, stuck in a groove. If his actions sometimes

appear random, it is only the contained chaos of one marble clicking off

another in the schoolyard, willy-nilly inside the tiny chalk circle but easily

predictable within the broad scheme of things. Eventually everything will

become clear, if not immediately then at some not-too-distant point.

The looming crooked edifice of the hospital is just visible in the

distance when the old man eases the truck down a dark narrow alleyway,

seemingly forgetting to brake until the nose of the truck is inches from the

sooty bricks of the alley"s terminal wall. Now the boy understands what"s

going on. This is the Jew"s back door, and the old man comes here with

almost the same regularity as he goes to the payroll office at the hospital a

mile down the road. The boy only takes the time to loosen the laces on his

boots before pressing his ear to the open window—his left ear, so he can turn

and face the scene taking pl...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherHoughton Mifflin Harcourt

- Publication date2003

- ISBN 10 0618251286

- ISBN 13 9780618251285

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages229

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 59.00

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

What We Lost

Published by

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

(2003)

ISBN 10: 0618251286

ISBN 13: 9780618251285

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks158524

Buy New

US$ 59.00

Convert currency

WHAT WE LOST

Published by

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

(2003)

ISBN 10: 0618251286

ISBN 13: 9780618251285

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.87. Seller Inventory # Q-0618251286

Buy New

US$ 75.18

Convert currency