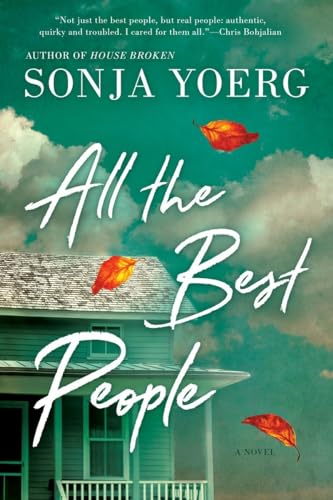

All the Best People - Softcover

Vermont, 1972. Carole LaPorte has a satisfying, ordinary life. She cares for her children, balances the books for the family’s auto shop and laughs when her husband slow dances her across the kitchen floor. Her tragic childhood might have happened to someone else.

But now her mind is playing tricks on her. The accounts won’t reconcile and the murmuring she hears isn’t the television. She ought to seek help, but she’s terrified of being locked away in a mental hospital like her mother, Solange. So Carole hides her symptoms, withdraws from her family and unwittingly sets her eleven-year-old daughter Alison on a desperate search for meaning and power: in Tarot cards, in omens from a nearby river and in a mysterious blue glass box belonging to her grandmother.

An exploration of the power of courage and love to overcome a damning legacy, All the Best People celebrates the search for identity and grace in the most ordinary lives.

CONVERSATION GUIDE INCLUDED

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Copyright © 2017 Sonja Yoerg

Chapter One

Carole

August 1972

Carole was ten when her mother was committed to Underhill State Hospital. For a rest, her father had said. By the time Carole was old enough to understand that the truth lay elsewhere, beyond her grasp, her mother had received insulin coma treatment for hysteria, colonics for depression, and electroshock just because, and Carole gave up wondering how her mother had lost control of her mind and simply coped with the fact that she had. Recently, Carole overhead the nurses say Solange Gifford was haunted, and although Carole did not, strictly speaking, believe in ghosts, it was as fitting a diagnosis as any.

She arrived at Underhill for her weekly visit a few minutes after nine and signed the register. A vase of lilies crowded the counter, the sweet musky scent mingling with the clinical bite of disinfectant and another smell, mushroomy and dark, that existed only here.

The receptionist greeted her and swiveled to face the switchboard.

“I’ll have them send your mother out, Mrs. LaPorte.”

“Thank you.” Carole felt her cheeks flush. She’d forgotten the woman’s name although she’d spoken with her a dozen times. “I’d like to go outside with her, if that’s all right.”

The woman smiled. If she was insulted at not being called by name, she hid it well. “We’ll have to see how she is, but I’ll let them know.”

Carole nodded and handed a small shopping bag across the counter. “Some blackberries for her. They’re coming on fast this year.”

She took a seat in the empty waiting area, the same seat she always chose, the left of the two between the ashcan and the magazine rack. Stale cigarette, bad as it was, countered the other odor. She leafed through an issue of Woman’s Day with Pat Nixon on the cover and suggestions for budget-friendly casseroles. One with tuna and cream of celery soup appealed to her, and her husband, Walt, was fond of celery, but she’d never remember how the recipe went. Someone had torn out a different recipe, ripped the page right down the middle, but Carole wouldn’t dream of doing such a thing. Even if she could bring herself to destroy public property, she’d never enjoy the meal.

An orderly came through the double door dividing the reception area from the wards and propped it open with his foot. “Mrs. LaPorte.”

She slid the magazine into the rack and stood, her legs heavy, her stomach queasy. She made her way down the corridor and glanced at the windows, set high, out of reach, and thought of the years, the thick stack of years her mother had been locked up here. Thirty-four years inside these brick walls, or barely outside them. Institutionalized. That word said it all. Long and cold and slammed shut at the end like a thick steel door.

The orderly escorted her into a lounge overlooking a slate patio beyond which lay a vast carpet of lawn. Solange stood beside the patio doors expectantly, reminding Carole of how her daughter’s cat waited by the backdoor to be let out. Her mother noticed her and smiled. Perhaps she was having one of her better days.

“Mama.” Carole rested her hand on Solange’s narrow shoulder and kissed her cheek. She led her mother to the patio and breathed deeply once they were outside. They set off by habit along the perimeter of the grounds.

They were not easy to pair as mother and daughter. Carole took after her father, lanky and square-shouldered, with dark blonde hair and eyes the color and shape of almonds. Her mother was petite and fair-skinned, and her eyes shifted from gray to green depending on the light and her mood. Solange’s hair was the color of concrete, but Carole easily remembered the deep red it had once been because she saw it every day on her daughter, Alison. “Red as an October maple,” her husband called it.

Solange walked slowly and with a hitch in her gait, as if she didn’t trust the ground, making her seem far older than sixty-five. Carole stayed close, her shoulder grazing her mother’s, in case she stumbled. It was better to visit this way instead of face-to-face, where Carole could be overrun with a hot sweet tide of pity, and if she looked at her mother directly, the way her eyes shifted out of focus rattled Carole. No, it wasn’t so much loss of focus as loss of presence. Solange’s eyes would film over, like those of a fish left gasping on the shore, and Carole would be uncertain where she had gone. “Inside herself” wasn’t accurate; the bottom had dropped out of whatever remained of her mother’s self. This loss, although temporary, was more acutely painful than the long-term loss of her. Carole was accustomed to her mother’s institutionalization, but she would never become accustomed to the idea that one day her mother might abandon reality entirely and never return.

They rounded the corner of the main building. Her mother asked, “How’s the baby?”

Carole answered the usual questions about her sister. “Janine’s fine. School starts in three weeks so it’ll be back to work for her.”

Solange hesitated. “Back to work?”

“Yes, Mama. Janine works in the school office. She’s thirty-four.”

Her mother shook her head. “Doesn’t seem possible. It truly doesn’t.”

“I know,” Carole said softly, as the passage of time frequently caught even the sane off guard. “She’s coming to visit soon, I hope.”

“Oh, that’s wonderful. She’s such a lovely baby.” Her voice drifted off.

Carole didn’t have the heart to correct her. For years she’d tried, insisting her mother work the logic through and accept that Janine was no longer a baby, or even a girl. But Solange would not utter the name Janine, and no amount of reasoning and explaining could alter her conviction that the infant she’d left behind had stayed small and vulnerable all these years. For Solange, time was a twisted landscape riddled with holes, and Janine the baby had fallen straight through.

Carole moved on to firmer ground. “Did you finish the apples I brought last week?”

“Apples? I think I had one recently. A McIntosh.”

“I’ve left some blackberries at the desk for you. They won’t last more than a few days, but I know how you like them.” Carole was never sure the staff gave Solange the food she brought, but she continued to bring it anyway. That and providing a few outfits a year was all she could do. It seemed so little. “Mama, how’s your friend, Maisie?” Manic-depressive, Maisie had been in and out of Underhill for years—mostly in.

“Maisie? She’s fine except when they have to lock her up. A lot of the others are leaving.”

Carole nodded. “I’m sorry the new medications don’t help you.”

“That’s all right. I never expected them to.”

They circled back to the patio and stopped to rest on an ironwork bench. A few other patients wandered nearby or slumped, sedated or catatonic, in wheelchairs.

Solange said, “As long as you and the baby are fine.”

Carole took her mother’s hand in hers. “We are, Mama. Don’t worry.” She didn’t pause to query herself before answering because, until recently, she had always been fine. She wouldn’t allow the strain to show. Not here.

The patio doors opened and a woman stepped out, holding a girl about one year old dressed in white and wearing a cap tied at the chin. A man, presumably the girl’s father, held an older gentleman by the elbow and directed him to a chair beside Carole and her mother. The older man worked his tongue in his mouth and his limbs trembled violently. The father sat next to him and bent his head in conversation. The child began to fuss, stretching her arms toward her father and kicking.

The mother held her tight. “Not now, sweetheart.”

Solange’s gaze had been drifting across the grounds, but now she studied the mother and daughter with intent.

Carole shifted to face her mother and touched her arm. “Mama?”

Solange continued to stare.

The girl squirmed against her mother’s grasp and whimpered. Within moments, the child’s frustration bloomed and she began to cry. The mother tried to soothe the girl but her cries only grew louder.

Solange stiffened and leapt from the bench. Carole’s arm shot out to stop her but it was too late. Solange grabbed the child by the shoulders. “Come to me, baby! I’m here!”

The woman twisted away in alarm, pulling her daughter closer. “Leave her alone!”

The girl’s father rose and stepped between his wife and Solange, his jaw set. Carole flew to her mother’s side.

The man scanned Carole’s face and her mother’s, assessing the likelihood both were a threat. He turned toward the building and shouted, “Orderly! Nurse!” The woman hurried inside, tucking the child’s head into her shoulder.

Solange’s eyes were wild and incredulous and filled with terror, as if no part of her comprehended her actions, much less her emotions. She held her arms outstretched, reaching after the baby. Her face contorted in a grimace, and she cried out, a long, low wail. Carole wrapped her arms around her, in protection, restraint, solace and fear. Her mother’s body was rigid and twitched as if electrified. Carole held on, her heart beating in her throat.

A nurse appeared, with a doctor and a syringe. Carole shook her head. “Please, give us a minute. Please.”

She ignored the impatience on the doctor’s face and the uncertainty on the nurse’s, and tended to her mother, stroking her hair and speaking into her ear in the most ordinary voice she could muster. “There were six deer in the field behind the house last night, Mama, lined up as if someone had arranged them. You could hardly see them, the grass being as high as it is on account of all the rain we’ve had. Walt’s been meaning to cut it but it’s been too wet and he’s been so busy—almost too busy—in the garage anyhow. And between you and me, I’d prefer to see the goldenrod bloom. Last show of summer, they are, and I’d sure hate to miss it.”

Solange’s limbs softened as Carole spoke, and her breathing slowed, though it still caught in her chest. A trickle of sweat ran down Carole’s back and her mouth was dry. The nurse helped her lower Solange onto the bench. The doctor disappeared. Carole knelt beside her mother and smoothed the damp hair from her forehead and stroked her cheek. Solange’s eyes were closed. Carole imagined her mother was knitting together pieces of herself before daring to look upon the world again. Or perhaps she was simply tired.

Several minutes passed. Solange slowly opened her eyes.

“Hello, Mama.”

She regarded her daughter. “Carole, dear. Is it visiting day?”

“Yes, it’s Sunday.”

“Are you making a dinner?”

Carole smiled. “Later, yes. If I can corral everyone.”

“Well, don’t let me keep you.” She looked around, as if seeing the day for the first time. “I’m just going to soak up a little sun.”

“All right, Mama. If you’re sure.” She kissed her cheek. “See you next week.”

Carole left Solange with the nurse, thanked the receptionist and returned to her Valiant. She drove through the village of Underhill and took Route 120 toward Adams. The smooth workings of the machine under her control and the changing views steadied her nerves, and she reflected on her mother. Solange hadn’t had a good day, but it hadn’t been an awful day, either. At least her mother wouldn’t spend this beautiful morning sedated and oblivious. It was bad enough they had to medicate Solange every night to stop her wandering in search of her baby. Locking the door was not enough, as she only rattled the handle and wailed. The nurses were probably right. Her mother was haunted by a baby lost in time.

Before Solange Gifford had been committed to Underhill, she had been, quite naturally, the center of Carole’s world. Then her mother was gone, leaving Carole confused and bereft. One of her aunts let slip that Solange was not tired but mad, which Carole at first took to mean she was angry. Shortly thereafter she learned the word “madhouse” and the significance of her mother’s disappearance swallowed her whole.

Everyone continued to call her sister “the baby” long after she’d been named, but she was nothing like the prim porcelain dolls on Carole’s dresser. She was swaddled fire, with powerful lungs and coal-black hair. Carole had promised her mother she would care for her sister and protect her, and although she’d been a child herself at the time, she’d done her best.

The road crested a hill, and Mount Mansfield, proud and solid, loomed before her. The spine along its north slope cast a deep shadow into the wooded valley. Later today the sun would find the valley, and tomorrow it would find it again. Normally, Carole would find honest reassurance in the regular sweep of the sun, the march of the hours, the parade of the seasons. She wasn’t the kind of person to pine for spring in January or to sigh when the first yellowed birch leaf fell to the ground. She didn’t slow her step to look over her shoulder and she certainly didn’t crane her neck around the corner of her future, wishing. But for months now something had shifted out of place, as if the mountains and the waters and the sky had been shaken up in a jar and put back together, but not perfectly. The seams were showing. It made no sense, but still.

Carole arrived at a T-junction and came to a stop. She signaled left and peered down the empty road in each direction. Adams was definitely to the left—she’d been here a thousand times—but a worm of uncertainty burrowed inside her. She looked to the right again, where the road divided pastures dotted with cows. On the far side, an old hay barn with a rusted roof slanted a few degrees toward the hill rising behind it. That way was Waterville, and beyond Waterville, Yardley. She was only confused because she hadn’t slept well for several weeks and it was catching up with her. That’s why everything seemed a little off. She was exhausted.

She glanced in the rearview mirror, unsure how long she’d been stopped in the road. No one was behind her. But she couldn’t afford to dawdle. She had to get home, clean the house, help Lester with his reading, get dinner ready and do a load of laundry so Walt would have a clean shirt to start the week. Oh, and she had to find the source of the error—over five hundred dollars—in the garage accounting. No doubt there were a hundred other things she had to do but was forgetting. A knot throbbed at the base of her skull. She studied the barn a second time, and the road, faded yellow lines down the middle. Pressure built at her temples. Carole let go of the wheel, stretched her fingers and gripped it again. Adams was to the left.

She was certain. Nearly.

Chapter Two

Alison

Alison slid off the beanbag and flicked off the television. The Brady Bunch had been boring as usual, but it was Delaney’s favorite, and it was her room and her television. Delaney grabbed her sketchpad and scooted onto her bed with the thirty-seven pillows, shaking her head so her silky brown mane fell perfectly across her shoulders. Alison didn’t have to see the sketchpad to know Delaney was drawing a bay mare with black markings, same as she always did. Correction. Her bay mare: Calamity Jane. Alison had once made the mistake of calling ...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherBerkley

- Publication date2017

- ISBN 10 0399583491

- ISBN 13 9780399583490

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages368

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 3.99

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

All the Best People [Paperback] Yoerg, Sonja

Book Description paperback. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # MAPA-3856-06-27-2022

All the Best People

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0399583491

All the Best People

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0399583491

All the Best People

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0399583491

All the Best People

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon0399583491

All the Best People

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0399583491

All the Best People

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new0399583491