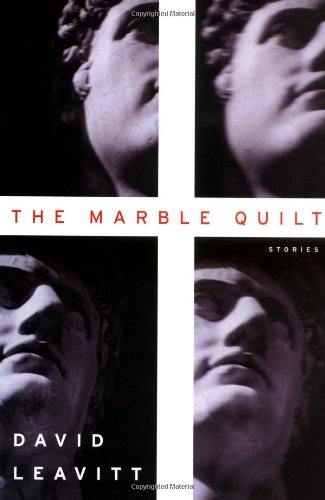

The Marble Quilt: Stories - Hardcover

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

It was the tunnel--its imminence--that all of them were contemplating

that afternoon on the train, each in a different way; the tunnel, at

nine miles the longest in the world, slicing under the gelid

landscape of the St. Gotthard Pass. To Irene it was an object of

dread. She feared enclosure in small spaces, had heard from Maisie

Withers that during the crossing the carriage heated up to a boiling

pitch. "I was as black as a nigger from the soot," Maisie Withers

said. "People have died." "Never again," Maisie Withers concluded,

pouring lemonade in her sitting room in Hartford, and meaning never

again the tunnel but also (Irene knew) never again Italy, never again

Europe; for Maisie was a gullible woman, and during her tour had had

her pocketbook stolen.

And it was not only Maisie Withers, Irene reflected now

(watching, across the way, her son Grady, his nose flat against the

glass), but also her own ancient terror of windowless rooms, of

corners, that since their docking in Liverpool had brought the

prospect of the tunnel looming before her, black as death itself (a

being which, as she approached fifty, she was trying to muster the

courage to meet eye to eye), until she found herself counting first

the weeks, then the days, then the hours leading up to the inevitable

reckoning: the train slipping into the dark, into the mountain. (It

was half a mile deep, Grady kept reminding her, half a mile of solid

rock separating earth from sky.) Irene remembered a ghost story she"d

read as a girl--a man believed to be dead wakes in his coffin. Was it

too late to hire a carriage, then, to go over the pass, as Toby had?

But no. Winter had already started up there. Oh, if she"d had her

way, they"d have taken a different route; only Grady would have been

disappointed, and since his brother"s death she dared not disappoint

Grady. He longed for the tunnel as ardently as his mother dreaded it.

"Mama, is it coming soon?"

"Yes, dear."

"But you said half an hour."

"Hush, Grady! I"m not a clock."

"But you said--"

"Read your book, Grady," Harold interrupted.

"I finished it."

"Then do your puzzle."

"I finished that, too."

"Then look out the window."

"Or just shut up," added Stephen, his eyes sliding open.

"Stephen, you"re not to talk to your brother that way."

"He"s a pest. Can"t a fellow get some sleep?"

Stephen"s eyes slid shut, and Grady turned to examine the

view. Though nearly fourteen, he was still a child. His leg shook.

With his breath he fogged shapes onto the glass.

"Did I tell you it"s the longest in the world? Did I tell you-

-"

"Yes, Grady. Now please hush."

They didn"t understand. They were always telling him to hush.

Well, all right, he would hush. He would never again utter a single

word, and show them all.

Irene sneezed.

"Excuse me," she said to the red-nosed lady sitting next to

her.

"Heavens! You needn"t apologize to me."

"It"s getting cold rather early this year," Irene ventured,

relieved beyond measure to discover that her neighbor spoke English.

"Indeed it is. It gets cold earlier every year, I find.

Judgment Day must be nigh!"

Irene laughed. They started chatting. She was elegantly got

up, this red-nosed lady. She knitted with her gloves on. From her hat

extended a fanciful aigrette that danced and bobbed. Grady watched

it, watched the moving mountains outside the window. (Some were

already capped with snow.) Then the train turned, the sun came

blazing into the compartment so sharply that the red-nosed lady

murmured, "Goodness me," shielded her eyes, pulled the curtain shut

against it.

Well, that did it for Grady. After all, hadn"t they just told

him to look at the view? No one cared. He had finished his book. He

had finished his puzzle. The tunnel would never arrive.

Snorting, he thrust his head behind the curtain.

"Grady, don"t be rude."

He didn"t answer. And really, behind the curtain it was a

different world. He could feel warmth on his face. He could revel in

the delicious sensation of apartness that the gold-lit curtain

bestowed, and that only the chatter of women interrupted. But it was

rude.

"Oh, I know, I know!" (Whose voice was that? The red-nosed

lady"s?) "Oh yes, I know!" (Women always said that. They always knew.)

Harold had his face in a book. Stephen was a bully.

"Oh dear, yes!"

Whoever was talking, her voice was loud. His mother"s voice

he could not make out. His mother"s voice was high but not loud,

unless she shouted, which she tended to do lately. Outside the window

an Alpine landscape spread out: fir groves, steep-roofed wooden

houses, fields of dead sunflowers to which the stuffy compartment

with its scratched mahogany paneling bore no discernible relation.

This first-class compartment belonged to the gaslit ambience of

stations and station hotels. It was a bubble of metropolitan,

semipublic space sent out into the wide world, and from the confines

of which its inmates could regard the uncouth spectacle of nature as

a kind of tableau vivant. Still, the trappings of luxury did little

to mask its fundamental discomforts: seats that pained the back,

fetid air, dirty carpets.

They were on their way to Italy, Irene told Mrs. Warshaw (for

this was the red-nosed lady"s name). They were on their way to Italy

for a tour--Milan, Venice, Verona, Florence, Rome (Irene counted off

on her fingers), then a villa in Naples for the winter months--

because her sons ought to see the world, she felt; American boys knew

so little; they had studied French but could hardly speak a word.

(Mrs. Warshaw, nodding fervently, agreed it was a shame.)

"And this will be your first trip to Italy?"

"The first time I"ve been abroad, actually, although my

brother, Toby, came twenty years ago. He wrote some lovely letters

for the Hartford Evening Post."

"Marvelous! And how lucky you are to have three handsome sons

as escorts. I myself have only a daughter."

"Oh, but Harold"s not my son! Harold"s my cousin Millie"s

boy. He"s the tutor."

"How nice." Mrs. Warshaw smiled assessingly at Harold. Yes,

she thought, tutor he is, and tutor he will always be. He looked the

part of the poor relation, no doubt expected to play the same role in

the lady"s life abroad that his mother played in her life at home:

the companion to whom she could turn when she needed consolation, or

someone to torture. (Mrs. Warshaw knew the ways of the world.)

As for the boys, the brothers: the older one looked

different. Darker. Different fathers, perhaps?

But Irene thought: She"s right. I do--did--have three sons.

And Harold tried to hide inside his book. Only he thought:

They ought to treat me with more respect. The boys ought to call me

Mr. Prescott, not Cousin Hal, for they hardly know me. Also, he

smarted at the dismissive tone with which Aunt Irene enunciated the

word tutor, as if he were something just one step above the level of

a servant. He deserved better than that, deserved better than to be

at the beck and call of boys in whom art, music, the classical world,

inspired boredom at best, outright contempt at worst. For though

Uncle George, God rest his soul, had financed his education, it was

not Uncle George who had gotten the highest scores in the history of

the Classics Department. It was not Uncle George whose translations

of Cicero had won a prize. Harold had done all that himself.

On the other hand, goodness knew he could never have afforded

Europe on his own. To his charges he owed the blessed image of his

mother"s backyard in St. Louis, his mother in her gardening gloves

and hat, holding her shears over the roses while on the porch the old

chair in which he habitually spent his summers reading, or sleeping,

or cursing--my God, he wasn"t in it! It was empty! To them he owed

this miracle.

"And will your husband be joining you in Naples?"

"I"m afraid my husband passed away last winter."

"Ah."

Mrs. Warshaw dropped a stitch.

The overdecorated compartment in which these five people were sitting

was small--four feet by six feet. Really, it had the look of a

theater stall, Harold decided, with its maroon velvet seats, its

window like a stage, its curtain--well, like a curtain. Above the

stained headrests wrapped in slipcovers embellished with the crest of

the railway hung six prints in reedy frames: three yellowed views of

Rome--Trajan"s Column (the glass cracked), the Pantheon, the

Colosseum (over which Mrs. Warshaw"s aigrette danced); and opposite,

as if to echo the perpetual contempt with which the Christian world

regards the pagan, three views of Florence--Santa Croce, the Duomo,

the Palazzo Vecchio guarded by Michelangelo"s immense nude David--

none of which Harold, who reverenced the classical, could see.

Instead, when he glanced up from his book, it was the interior of the

Pantheon that met his gaze, the orifice at the center of the dome

throwing against its coffered ceiling a coin of light.

He put down his book. (It was Ovid"s Metamorphoses, in Latin.) Across

from him, under the Pantheon, Stephen sprawled, his long legs in

their loose flannel trousers spread wide but bent at the knees,

because finally they were too long, those legs, for a compartment in

which three people were expected to sit facing three people for hours

at a time. He was asleep, or pretending to be asleep, so that Harold

could drink in his beauty for once with impunity, while Mrs. Warshaw

knitted, and Grady"s head bobbed behind the curtain, and Aunt Irene

said she knew, she knew. Stephen was motionless. Stephen was

inscrutable. Still, Harold could tell that he too was alert to the

tunnel"s imminence; he could tell because every few minutes his eyes

slotted open, the way the eyes of a doll do when you tilt back its

head: green and gold, those eyes, like the sun-mottled grass beneath

a tree.

He rarely spoke, Stephen. His body had the elongated

musculature of a harp. His face was elusive in its beauty, like those

white masks the Venetians wear at Carnival. Only sometimes he shifted

his legs, in those flannel trousers that were a chaos of folds, a

mountain landscape, valleys, passes, peaks. Most, Harold knew, if you

punched them down, would flatten; but one would grow heavy and warm

at his touch.

And now Harold had to put his book on his lap. He had to. He

was twenty-two years old, scrawny, with a constitution his doctor

described as "delicate"; yet when he closed his eyes, he and Stephen

wore togas and stood together in a square filled with rational light.

Or Harold was a great warrior, and Stephen the beloved eremenos over

whose gore-drenched body he scattered kisses at battle"s end. Or they

were training together, naked, in the gymnasium.

Shameful thoughts! He must cast them out of his mind. He must

find a worthier object for his adoration than this stupid, vulgar

boy, this boy who, for all his facile handsomeness, would have hardly

raised an eyebrow in the age of Socrates.

"Not Captain Warshaw, though! The Captain had a stomach of iron."

What were they talking about? The Channel crossing, no doubt.

Aunt Irene never tired of describing her travel woes. She detested

boats, detested hotel beds, hated tunnels. Whereas Harold, if anyone

had asked him, would have said that he looked forward to the tunnel

not as an end in itself, the way Grady did, but because the tunnel

meant the south, meant Italy. For though it did not literally link

Switzerland with Italy, on one side the towns had German names--

Göschenen, Andermatt, Hospenthal--while on the other they had Italian

names--Airolo, Ambri, Lurengo--and this fact in itself was enough to

intoxicate him.

Now Stephen stretched; the landscape of his trousers surged,

earthquakes leveled the peaks, the rivers were rerouted and the crust

of the earth churned up. It was as if a capricious god, unsatisfied

with his handiwork, had decided to forge the world anew.

"Ah, how I envy any traveler his first visit to Italy!" Mrs. Warshaw

said. "Because for you it will be new--what is for me already faded.

Beginning with Airolo, the campanile, as the train comes out the

other end of the tunnel . . ."

Harold"s book twitched. He knew all about the campanile.

"Is it splendid?" Irene asked.

"Oh, no." Mrs. Warshaw shook her head decisively. "Not

splendid at all. Quite plain, in fact, especially when you compare it

to all those other wonderful Italian towers--in Pisa, in Bologna. I

mustn"t forget San Gimignano! Yes, compared to the towers of San

Gimignano, the campanile of Airolo is utterly without distinction or

merit. Still, you will never forget it, because it is the first."

"Well, we shall look forward to it. Grady, be sure to look

out for the tower of . . . just after the tunnel."

The curtain didn"t budge.

Irene"s smile said: "Sons."

"And where are you traveling, if I might be so bold?"

"To Florence. It"s my habit to spend the winter there. You

see, when I lost the Captain, I went abroad intending to make a six-

months tour of Europe. But then six months turned into a year, and a

year into five years, and now it will be eight years in January since

I last walked on native soil. Oh, I think of returning to Toronto

sometimes, settling in some little nook. And yet there is still so

much to see! I have the travel bug, I fear. I wonder if I shall ever

go home." Mrs. Warshaw gazed toward the curtained window. "Ah,

beloved Florence!" she exhaled. "How I long once again to take in the

view from Bellosguardo."

"How lovely it must be," echoed Irene, though in truth she

had no idea where Bellosguardo was, and feared repeating the name

lest she should mispronounce it.

"Florence is full of treasures," Mrs. Warshaw continued. "For

instance, you must go to the Palazzo della Signoria and look at the

Perseus."

Harold"s book twitched again. He knew all about the Perseus.

"Of course we shall go and see them straightaway," Irene

said. "When do they bloom?"

When do they bloom!

It sometimes seemed to Harold that it was Aunt Irene, and not

her sons, who needed the tutor. She was ignorant of everything, and

yet she never seemed to care when she made an idiot of herself. In

Harold"s estimation, this was typical of the Pratt branch of the

family. With the exception of dear departed Toby (both of them), no

one in that branch of the family possessed the slightest receptivity

to what Pater called (and Harold never forgot it) "the poetic

passion, the desire of beauty, the love of art for its own sake."

Pratts were anti-Paterian. Not for them Pater"s "failure is forming

habits." To them the formation of habits--healthy habits--was the

very essence of success. (It was a subject on which Uncle George, God

rest his soul, had taken no end of pleasure in lecturing Harold.)

Still, Harold could not hate them. After all, they had made

his education possible. At Thanksgiving and Christmas they always had

a place for him at their table (albeit crammed in at a corner in a

kitchen chair). "Our little scholarship boy," Aunt Irene called

him. "Our little genius, Harold."

Later, after Uncle George had died, and Toby had di...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherHoughton Mifflin Harcourt

- Publication date2001

- ISBN 10 0395902444

- ISBN 13 9780395902448

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages241

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 5.45

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Marble Quilt: Stories

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. In shrink wrap. Seller Inventory # 100-19996

The Marble Quilt: Stories

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0395902444

The Marble Quilt: Stories

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0395902444

The Marble Quilt: Stories

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0395902444

The Marble Quilt: Stories

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0395902444

THE MARBLE QUILT: STORIES

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.9. Seller Inventory # Q-0395902444