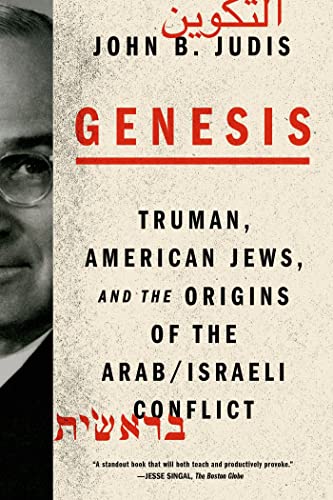

Genesis: Truman, American Jews, and the Origins of the Arab/Israeli Conflict - Softcover

A probing look at one of the most incendiary subjects of our time―the relationship between the United States and Israel

There has been more than half a century of raging conflict between Jews and Arabs―a violent, costly struggle that has had catastrophic repercussions in a critical region of the world. In Genesis, John B. Judis argues that, while Israelis and Palestinians must shoulder much of the blame, the United States has been the principal power outside the region since the end of World War II and as such must account for its repeated failed diplomacy efforts to resolve this enduring strife.

The fatal flaw in American policy, Judis shows, can be traced back to the Truman years. What happened between 1945 and 1949 sealed the fate of the Middle East for the remainder of the century. As a result, understanding that period holds the key to explaining almost everything that follows―right down to George W. Bush's unsuccessful and ill-conceived effort to win peace through holding elections among the Palestinians, and Barack Obama's failed attempt to bring both parties to the negotiating table. A provocative narrative history animated by a strong analytical and moral perspective, and peopled by colorful and outsized personalities and politics, Genesis offers a fresh look at these critical postwar years, arguing that if we can understand how this stalemate originated, we will be better positioned to help end it.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

THE ORIGINS OF ZIONISM: HERZL, AHAD HA’AM, AND GORDON

If you had been alive in the mid-nineteenth century and visited the land that would become Palestine and then Israel, you would have found few signs of the conflict that would later tear the country apart. You would have heard references to “Palestine,” but you wouldn’t have found a nation with its own laws and government that corresponded to Palestine or Israel. The Turks, who ruled the region, divided the land into three parts for purposes of collecting taxes. The West Bank was part of the province of Syria; northern Palestine was part of the province of Beirut; and Jerusalem and its environs had their own district.

According to one estimate, the area corresponding to Palestine had about 340,000 people, of whom 300,000, or 88 percent, were Muslims or Druze, 27,000, or 8 percent, Christians, and 13,000, or 4 percent, Jews.1 Many of these Jews lived in Jerusalem, Nablus, and Hebron. A few were well-to-do descendants of Sephardic émigrés from Spain, but many were more recent émigrés from Europe who devoted themselves to religious study and prayer and survived off donations from abroad.

The Jews of Palestine suffered religious persecution, but no different from that inflicted on Christians in a society dominated by Muslims. For instance, both Jews and Christians were officially prohibited from building new houses of worship, but both groups were able to use bribes to get around the law. There was nothing like the wave of anti-Semitism that would sweep Europe during the late nineteenth century. “Jews enjoyed a higher standing in Muslim society and enjoyed a greater affinity with the culture of their surroundings than the Jews in Eastern Europe,” wrote the historian Yosef Gorny.2

There was also little of a Western presence in the region. Americans were preoccupied with the Civil War and its aftermath. The great powers of Europe were just beginning to divide up Asia and Africa. The British had an interest in allying themselves with the Turks against the Russians, they were about to gain a foothold in Egypt, and they had begun to consider Palestine and its environs as a path eastward, but they had not done anything about it, and would not do so for the rest of the century.

There were rabbis and some notable Christians in Europe and the United States who thought the Jews should return to Palestine. The Christians were called “restorationists,” and in Britain they were able to attract support for their views among high officials who saw a Jewish Palestine in commercial or imperial terms. But most Jews accepted the Diaspora as an enduring condition. The Orthodox thought that the Jews would eventually return to Zion, but by a Messianic act of God rather than by an organized mass migration. Jews declared “Next year in Jerusalem” annually during Passover dinners, but few took these words literally.

Then, over the next forty years—from the 1880s to the end of World War I and the early 1920s—the region was utterly transformed. The Ottoman Empire was dissolved, a casualty of Turkey’s alliance with Germany during World War I. Through a League of Nations mandate, Britain assumed control of Palestine, an area that initially included what became Transjordan and later Jordan, but it administered the two areas separately. As a result, the western part of the mandate, administered through Jerusalem, became known again as Palestine, the name the Romans had originally given the country, but that also had a more ancient root in the seafaring Philistines who were contemporaries of the Old Testament Jews.

By 1922, according to a British census, Palestine’s population had grown to 752,048, of which Jews accounted for 83,900, or 11 percent. The sevenfold increase in the Jewish population had been spurred by the development of a Zionist movement in Europe, particularly in the Russian Pale of Settlement, which was in response to the simultaneous growth of nationalism and anti-Semitism in Central and Western Europe. Zionism was Jewish nationalism, but unlike German or Romanian nationalism, it was not centered on an existing homeland but on one that Jews had once inhabited and now wanted to return to.

The outward logic of Zionism was impeccable. The nations of Europe, where Jews had dwelt for hundreds of years, were treating them as a nation in their midst. Nationalist politicians and intellectuals in Central and Eastern Europe called for purging their countries of this alien nation. In response, Jews wanted a genuine nation of their own where they could be secure from persecution and oppression. The trouble came when Zionists specified where that nation should be. Two thousand years before, most Jews had lived in Palestine, and a few thousand still did. But other peoples had also inhabited Palestine over the millennia, and Arabs had lived there for 1,400 years. If Zionism’s objective was to establish a Jewish state in Palestine, that meant ruling over or driving out the Arabs who already lived there.

In justifying their attempt to colonize Palestine, some Zionists—who cited the influence of the Russian Zionist Ahad Ha’am—tried to come to terms with the Arab presence in Palestine. But many Zionists, following the example of Theodor Herzl, the Viennese author of The Jewish State, fell back on the same kind of rationalizations that the great powers had advanced in attempting to extend their reach over Asia and Africa, and that Christian Europe, and that Christian restorationists, and even before them, the Crusaders, had used to justify the conquest of Palestine. They promised to reclaim Palestine for the religion of the Bible, to civilize the Arabs, and to revive the land that, they claimed, the Arabs had allowed to become a desolate wasteland. Most American Zionist leaders would trace their lineage back to Herzl rather than to Ahad Ha’am and would adopt a distorted understanding of Palestine and its Arab inhabitants.

Anti-Semitism and Zionism

The idea of a Jewish return to Zion (which originally referred to Jerusalem) goes back to the Babylonian captivity in the sixth century B.C.E. and was promoted over the centuries by a succession of Jewish rabbis and mystics. The English Puritans, including those who settled in New England, believed on biblical grounds in a Jewish return to the region of Palestine. Napoleon advocated a Jewish state during his eastern campaign in 1799. And in the early nineteenth century, British officials, led by the Christian revivalist Lord Shaftesbury, called on Britain to promote a Jewish return to the Holy Land.

By midcentury, there was some stirring among Jewish intellectuals. In the 1860s, the German Socialist Moses Hess, a former comrade of Karl Marx, and the Polish rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer, both of whom were deeply impressed by the Italian movement for national unification, Il Risorgimento, advocated the gradual creation of a Jewish state. But the birth of a Zionist movement—and the beginning of emigration—had to wait until the 1880s, till the outbreak of anti-Semitism in Russia and Eastern Europe and its spread westward. This turned Jewish Zionism from a religious fantasy into a political movement.

Jews, of course, had suffered persecution for centuries, but much though not all of it was based on their beliefs and what they were reputed to have done to Jesus Christ. It was religious persecution. By contrast, nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century anti-Semitism was primarily a toxic blend of nationalism, racism, and imperialism directed at Jews as an alien national group within nations or empires rather than as a religious group among other religions. It coincided with the rise throughout Europe of the unified nation state and of national rebellions against empires.

In the nineteenth century, Italians and Hungarians sought to free themselves from the Austro-Hungarian Empire; Romanians and other Balkan peoples from the Ottoman Empire; the Poles from the Russian Empire; and Germans from the Hapsburgs and from the legacy of defeat in the Napoleonic wars. They defined their national aspirations along ethnic and quasi-racial lines that led them to see Jews as an alien nation. Johann Gottlieb Fichte, a father of German nationalism, described Germans as a race that nature “joined to each other in a multitude of invisible bonds” and Jews as “a state within a state.” Fichte infamously declared that he could only imagine granting civil rights to Jews if one were “to cut off all their heads in one night, and to set new ones on their shoulders, which should contain not a single Jewish idea.”3

In Austria and Russia, defenders of the empire invoked their own brand of nationalism against the secessionists and against Jews, whom they blamed for the unrest. In Austria, George Ritter von Schönerer built a pan-German movement based on the premise that Austria had to rid itself of Jewish influence.4 In Russia, the Black Hundreds swore loyalty to the czar and Russian absolutism while leading violent assaults against Jews.

This fusion of religious intolerance, national chauvinism, and what the Russian Zionist Leo Pinsker called “demonopathy” inspired new laws threatening Jews’ livelihood and led to a succession of violent pogroms in Russia and the Russian Pale of Settlement—the western edge of the Russian empire to which the czarist regime restricted Jews. In the spring of 1881, massive anti-Jewish riots took place in response to false rumors that the Jews had assassinated Alexander II. These riots, in which Jews were killed and homes and synagogues destroyed, spread to 160 cities and villages in the Pale and recurred over the next four decades. The American ambassador wrote, “The acts which have been committed are more worthy of the Dark Ages than of the present century.”5

In Eastern and Southern Europe, nationalist movements, seeking to throw off Austrian or Turkish rule, turned violently against the Jews. In Central and Western Europe, where Jews were no longer confined to ghettos, anti-Semitic movements and parties, typified by Karl Lueger’s Austrian Christian Social party and Adolf Stoecker’s party of the same name in Germany, directed their ire at the least and most successful Jews. They stirred fear that poverty-stricken Jewish immigrants from Russia and Eastern Europe were creating new ghettos while at the same time they excoriated wealthy, successful Jews who had lived in Germany and Austria for generations and who were assuming high positions in the professions, government, and the media. These parties called for restricting immigration and setting quotas for Jews in professions and universities. In France, an upsurge in anti-Semitism in the 1880s and ’90s culminated in the frame-up, trial, and conviction of the Jewish army captain Alfred Dreyfus for treason.

By stigmatizing Jews as an alien nation rather than as a religious group, the new anti-Semitism inspired Jews to consider whether, if they were a national group, they needed a land-based nation of their own. And the pogroms lent urgency to the task. While the first great Zionist tract, Hess’s Rome and Jerusalem, was ignored during his lifetime, the Russian Zionists of the 1880s, writing in the wake of the pogroms, were able to parlay their readership into an organized following.

The first two prominent Russian Zionists, Moshe Leib Lilienblum and Leo Pinsker, became Zionists in the wake of the pogroms. Lilienblum was a Talmudic scholar who, after breaking with the rabbinical orthodoxy, fled to Odessa, the capital of Jewish modernism. Pinsker was born in Russian Poland, the son of a distinguished Hebrew scholar. He was trained as a physician at the University of Moscow. He practiced in Odessa and was honored by Czar Nicholas I for his treatment of soldiers during the Crimean War.

Pinsker initially advocated Jewish assimilation, or “Russification” through the use of the Russian language and education in Russian culture. He was a leading member of the Society for the Spread of Culture among the Jews of Russia. But the pogroms turned him to Zionism. He resigned from the Society for the Spread of Culture and in 1882 published Auto-Emancipation, which helped inspire the Zionist movement in Russia. According to Pinsker, the Jews’ problem was that “among the nations under which they dwell,” they were the “ghost” of a nation rather than a real nation. Even after leaving Palestine, “they lived on spiritually as a nation,” but “they lack a certain distinctive national character, inherent in all other nations, which is formed by common residence in a single state.”6 That accounted for what Pinsker called “Judeophobia.” “If the fear of ghosts is something inborn, and has a certain justification in the psychic life of mankind,” he wrote, “why be surprised as the effect produced by this dead but still living nation.”7

Pinsker was convinced that Judeophobia was unavoidable as long as Jews were scattered as foreign bodies in the midst of other nations. “As a psychic aberration it is hereditary,” he wrote, “and as a disease transmitted for two thousand years, it is incurable.” Lilienblum, writing in 1883, was similarly pessimistic: “Civilization, which could virtually deliver us from those persecutions which have a religious basis, can do nothing at all for us against those persecutions that have a nationalistic basis.”8

Pinsker’s solution was not to fight Judeophobia. “We must give up contending against these hostile impulses as we must against every other inherited predisposition,” he wrote.9 Instead, Jews must eliminate the ghosts by establishing a real nation of their own. “Grant us our independence, allow us to take care of ourselves, give us but a little strip of land like that of the Serbians and Romanians, give us a chance to lead a national existence and then prate about our lacking manly virtues.”10

Pinsker thought that Palestine was the likely site of a Jewish state, but he didn’t claim Jewish title on biblical grounds. “The goal of our present endeavors must be not the ‘Holy Land,’ but a land of our own,” he wrote.11 Lilienblum was more willing to evoke past ownership. “Why should we be strangers in Gentile countries,” he asked, “while the land of our fathers has not yet disappeared from the face of the earth, is still desolate, and can, along with its neighboring environs, incorporate our people?”12

Lilienblum’s question, which was really an assertion, lay at the heart of early arguments for Zionism. While a few secular Jews like Pinsker eschewed biblical claims to Palestine, most Zionists did not—and that included secular Zionists like the young Pole David Ben-Gurion. Zionists regarded Palestine as the Jews’ home from which they had been unjustly expelled by the Romans in the first and second centuries C.E., and to which they were fully entitled to return and to lay claim as their own.

This conception of Zionism, rooted in the Old Testament, rested on a mythic version of Palestine. In fact, the land from “Dan to Beersheba” that the Jews briefly ruled was home to many different peoples and tribes.13 The area was also a “land of passage” in the Middle East through which different peoples entered and left—some voluntarily, some forcibly. In historical terms, the Zionist claim to Palestine had no more validity than the claim by some radical Islamists to a new caliphate. Nevertheless, this argument for Zionism, based on the Old Testament, carried great weight.

It was reinforced by Christian Zionism and its conception of Palestine as a “holy land” that had been despoiled by Islamic infidels. That idea went back to the Crusades, but it had been reshaped by the Christian Restorationists in the nineteenth century who called for a Jewish return to Palestine. It...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherFarrar, Straus and Giroux

- Publication date2015

- ISBN 10 0374535124

- ISBN 13 9780374535124

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages448

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Genesis: Truman, American Jews, and the Origins of the Arab/Israeli Conflict

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. 0.75. Seller Inventory # 0374535124-2-1

Genesis: Truman, American Jews, and the Origins of the Arab/Israeli Conflict

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published 0.75. Seller Inventory # 353-0374535124-new

Genesis: Truman, American Jews, and the Origins of the Arab/Israeli Conflict (Paperback or Softback)

Book Description Paperback or Softback. Condition: New. Genesis: Truman, American Jews, and the Origins of the Arab/Israeli Conflict 0.8. Book. Seller Inventory # BBS-9780374535124

Genesis: Truman, American Jews, and the Origins of the Arab/Israeli Conflict

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Brand New! This item is printed on demand. Seller Inventory # 0374535124

Genesis: Truman, American Jews, and the Origins of the Arab/Israeli Conflict

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # I-9780374535124

Genesis: Truman, American Jews, and the Origins of the Arab/Israeli Conflict

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0374535124

Genesis: Truman, American Jews, and the Origins of the Arab/Israeli Conflict

Book Description Condition: New. . Seller Inventory # 52GZZZ010MDR_ns

Genesis: Truman, American Jews, and the Origins of the Arab/Israeli Conflict

Book Description Condition: New. 448. Seller Inventory # 26372243068

Genesis: Truman, American Jews, and the Origins o

Book Description Condition: New. Special order direct from the distributor. Seller Inventory # ING9780374535124

Genesis: Truman, American Jews, and the Origins of the Arab/Israeli Conflict

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0374535124