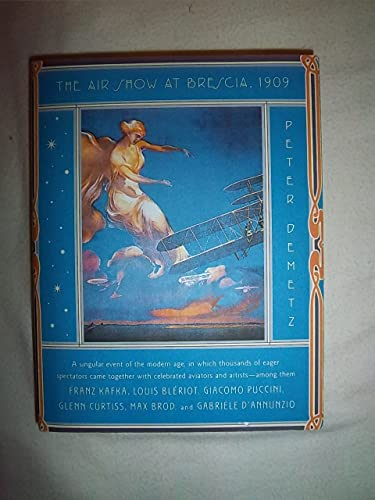

The Air Show at Brescia, 1909 - Hardcover

In 1909, municipal authorities built an airfield in northern Italy and invited leading pilots to compete on it. The show attracted thousands of spectators--among them Giacomo Puccini and Gabriele d'Annunzio--and reporters, including, amazingly, Franz Kafka, Max Brod, and Luigi Barzini. Peter Demetz's sparkling new book tells the enchanting story of what happened in the air and on the ground before, during, and after this amazing moment.

Kafka, it turns out, was a very precise observer of both the fragile new machines and the people who flocked to see them in action. Demetz shows us the spectacle as Kafka reported it, and also its unexpectedly melodramatic preparations, amazing dirigibles, and ace pilots--the American Glenn Curtiss, the Italian Mario Calderara, and the reigning king of the skies, Louis Blériot.

But above all Demetz wants to know what flying really meant to these visionaries of the air: many political and imaginative issues were sent aloft at Brescia. With discerning affection, he elucidates Kafka's subtle ambiguities about the consequences of flight, d'Annunzio's lust for power in aviation, Puccini's enthusiasm for speedy escapes, and Curtiss's modest heroism. Illustrated with fascinating material from the show itself, this provocative work reveals a vital point where art and technology met in imagining the future.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

CHAPTER ONEThree Friends, VacationingIN LATE AUGUST 1909, three Prague friends in their twenties, and of more or less similar literary and artistic interests, thought of going together on a brief vacation. They wanted to escape from their gray old city and their office routines and stay for a few days at Riva, on the north shore of Lake Garda, the last outpost of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy and deep in Italian-language territory. The youngest of them, twenty-one-year-old Otto Brod, a bank trainee, had been there a year earlier and brought back glowing reports about the towering mountains, the sailboats on the glittering lake, the palm trees, and the celebrated people who gathered there. He had even met Heinrich Mann, less bourgeois than his brother Thomas, and together they had mailed a postcard to Prague showing Heinrich before the mast of a boat, with Otto in attendance as a kind of deckhand, and Heinrich had written, "Nothing was more important to an artist than the admiration of the young who had not yet yielded to enthusiasm too often." Otto suggested to his twenty-five-year-oldbrother Max, a lawyer in the service of the Prague Central Post Office and a published writer known beyond his hometown, as well as to his friend the twenty-six-year-old Franz Kafka, who had begun to work for an insurance company, that they all go south together.The brothers Brod had an easy time looking forward to the trip, for they had shared many vacations as children and teenagers, mostly at Misdroy, on the German shore of the Baltic Sea, the preferred watering spot of well-to-do Prague acculturated Jewish families at the turn of the century. Kafka, of a Jewish family of somewhat lower standing (his father, son of a kosher butcher, owned a reputable textile shop), had once accompanied a rich relative to the North Sea, but had never gone south of the Bohemian border. He felt a little anxious about imposing his presence on the two brothers and did not immediately make up his mind, but then apologized to Max in one of his frequent letters, saying, "If anybody had made such difficulties as I did yesterday, I would have thought twice before deciding whether to take him to Riva or not."On Saturday, 4 September 1909, Kafka and Brod left Prague Central Station (Otto Brod was to follow immediately), and I assume that they took the fast train to Munich and switched there to the Innsbruck connection. Proceeding from Innsbruck over the Brenner Pass, they went to Bozen in the South Tyrol, in order to catch the train to Verona. The Baedeker Travel Guide, bible for all Austrian and German tourists, indicated that travelers had to change at the little station of Mori for a local connection to Riva, about twenty-five kilometers distant; and it is easy toimagine that the three young men, short on cash, paid one crown and sixty kreuzers each for a second-class ticket rather than three crowns and twenty kreuzers for first class. They traveled on that little train through a green valley to the lake of Loppio and from there up to a mountain pass, descending again toward the town of Torbole, and enjoyed a magnificent view of Lake Garda before reaching Riva.At that time, Riva was a lively place of nearly eight thousand inhabitants, mostly busy in the modest tourist industry. (When I visited there recently, many tourist buses, most of them from places in former East Germany, were parking in the most improbable corners.) In 1909 there were about eight hotels and pensions (of fourteen) recommended especially by the Baedeker, the elegant Hotel Lido, Hotel Zur Sonne, and Hotel du Lac, but also a few simpler places like the See Villa or the Zentralhotel near the railway station. It was a tourist must to marvel at the Rocchetta, a steep rock crowned with a decrepit tower built in the distant past by the Venetians, and to admire the picturesque harbor square with arcades and an ancient tower with a clock. The sunny scene neatly impressed itself on Kafka's memory for a long time.

MY TRAVELOGUE, with its fast and slow trains, blue skies, picturesque rocks, and the lake, has been all too particular so far. But with Kafka, matters were, as usual, rather complicated, though not all difficulties were of his own making. The simple question was whether he would be allowed by his office superiorsto take a vacation at all, even a brief one. Kafka had received his law degree on 18 June 1906, then worked for a while in the office of a Prague uncle, and continued on for a year as a court intern. But it was not easy for a young Jewish lawyer to find a suitable job. His family was concerned and turned to the "Madrid uncle," an almost mythic figure. (He was one of the directors of the Spanish railroad system and a man of many contacts.)A job as Aurshilfskraft (temporary assistant) was found at the Assicurazioni Generali of Trieste, a prominent Italian insurance company with a branch office in Prague. He had to work there eight to ten hours every day, was not paid for overtime, and was given the privilege of being permitted to apply for vacation time only after serving two full years. At the start, he felt elated, began to study a little Italian, and hoped the company would send him to Trieste for future training. After a few weeks in the office, located in the heart of the city at Wenceslas Square, his affair with an intelligent young woman of socialist leanings was going awry, and in the spring of 1908, young Kafka returned to his usual and lonely consolations in the night cafés and brothels. By late spring, his situation at the Assicurazioni had become untenable, and he had to mask his efforts to look for a job elsewhere. Fortunately, the father of one of his former schoolmates--an insurance manager of importance named Dr. Otto Píbram, president of the General Accident Insurance Company--made certain that a job was offered to the young lawyer. It was a meager position, though with excellent prospects, and Kafka accepted it immediately, making him the second Jew (notcounting the president) among 250 employees. He was to work there loyally until 1922, when he was furloughed because of his grave illness.Though he again started as a mere Aushilfskraft, Kafka's new job offered remarkable advantages to an employee who seriously wanted to get ahead in the insurance business and do his own writings, sorely neglected for quite a while. It was a job "mit einfacher Frequenz," that is, office hours from 8:00 A.M. to 2:00 P.M., allowing Kafka to return home for an afternoon nap, to walk with his friends through the Prague streets or parks, and to work later on his own prose, if the mood was right (it seldom was). His superiors, especially Dr. Robert Marschner, liked him well enough, and sent the newcomer on factory inspection trips through the industrial regions of northern Bohemia. Quietly recognizing his literary intelligence, Dr. Marschner asked him to write technical analyses that were published regularly in the yearbook of the company; after eight months, his superiors praised his eminent loyalty and diligence, his commitment to his agenda, and his "literary talents."Yet he was not content; he had not had a vacation for three years (his last he had spent at the Silesian mountain resort of Zuckmantel, where he found himself happily involved with an older woman), and he felt listless and chafed under the strict rules making him ineligible for vacation time. As early as 17 June 1909, he submitted a petition, on company stationery, claiming that he, for some time now, was suffering from a pathologically nervous condition that caused prolonged digestive problems and insomnia. On 18 August, now with the Riva plans in the air, hefollowed up with a certificate by a friendly physician confirming that Dr. Franz Kafka, after three long years without any vacation, "has begun to feel fatigued and nervous and to suffer from frequent headaches." From a purely medical point of view, it was necessary that the patient "take a holiday, even if only for a short while." The company behaved well. Forty-eight hours later, Kafka was notified (so much for the famous old Austrian bureaucracy) that his petition had been granted, and on 20 August he was informed that, by extraordinary permission of the director, he was free to take a requested vacation of eight days.It does not seem that our three friends were too concerned with how short their vacation was actually to be, considering how long it would take them to get from Prague to Riva and return. They settled at the inexpensive Pension Bellevue, not listed by the Baedeker but close to the Rocchetta and with a nice view, spent a good deal of time hanging around the veranda, and went on an excursion to Castle Toblino. A rare photograph shows Otto and Franz, with floppy hats against the sun, rigging up a little boat, very sportif and yet curiously serious. Most of the time, I assume, they spent at the Bagni della Madonna under the Ponale Road, hewn into the rocks (it was less expensive than the bathing establishment at the Hotel Lido). Even after many years, Max Brod recalled "the long gray wooden boards in the sun ... , the glistening lizards, the cool quietness of the place," and felt that they were really welcomed here by "the classic simplicity of the south," as the renowned eighteenth-century critic Winckelmann called it.Between swims they liked to read, enjoying their little Italian, and the Sentinella Bresciana, the Italian daily published across the border. The issue of 9 September, to which Kafka later referred, immediately caught their interest. It would have been impossible, anyway, to ignore the headline splashed over page one: La Prima Giornata del Circuito Aereo (The First Day of the Air Show). As restless on vacation as he was at home, if not more so, Kafka immediately suggested to his friends that they all go to Brescia, Brod recalled, and since they had never seen any airplane in flight (though Brod had written an article on the famous French pilot Louis Blériot for a Berlin paper), they decided to go before it was too late. On the morning of 10 September they went by lake steamer to Desenzano, a trip of nearly five hours, making stops at Limone, Campione, Gargnano, Maderno, Gardone, Salò (which would be Mussolini's last stand), and Catullus's Sirmione. At Desenzano, they took the local train to Brescia Main Station, with its theatrical turrets and false crenellations. (They did not know that in the Austro-Italian war of 1859, Josef Rilke, father of their Prague fellow poet Rainer Maria Rilke, had been the commander of Brescia Castle.)The three friends were having a good time together, kidding, laughing, walking, rowing, and swimming, but they did not show much interest in literary matters--seemingly. At the bathing establishment, they almost inevitably met and talked to the Tyrolean poet and nature apostle Carl Dallago, who quoted Nietzsche and Walt Whitman and, possibly, made a nuisance of himself. Max Brod testily remarked that Dallago "lived" (hauste) on the wooden planks of the Bagni, but his commitmentto an alternative way of life and to vegetarian nourishment was tremendously interesting to Kafka, who later came to read Dallago's contributions to the famous Innsbruck periodical Der Brenner, which was also committed to the poetry of Georg Trakl.Max Brod had other plans; he had always been intensely involved in the literary affairs of his friends, especially if they did not publish as much as he did; he interfered, cajoled, and wrote endless letters of recommendation. He had good contacts among German publishers, and felt frustrated when it was impossible for him to put these contacts at the disposal of his friends; it is more than probable that Brod opened Franz Werfel's way to glory, and he certainly eased Kafka's way into print. By 1909 Brod was well known in Prague and Berlin as an enterprising young writer of considerable aesthetic finesse and an addict of Schopenhauer. Already he had written a collection of novellas and a volume of poetry (published in 1907), and his 1908 novel, Schloss Nornepygge (Castle Nornepygge), had created a remarkable stir among the Berlin expressionists. The following year his novella Ein tschechisches Dienstmädchen (A Czech Servant Girl) challenged both Prague Zionists as well as Czech patriots, who argued in unison that the ancient Prague conflicts of nationalities could not be solved as easily as the novelist thought. Kafka, in some contrast to his friend Max Brod, had composed, before going to Riva, only a curious medley of a few meditative texts, a partly disheveled review of Franz Blei's rococo keepsake for society ladies, not exactly Kafka's cup of tea, two fragments of an early prose piece, and an important legal article on the insuranceresponsibilities of construction companies (published in 1908). Brod believed that Kafka was right in wanting to go to the air show. A new experience might break his writer's block, and he suggested that they might enter into a friendly competition: they would both write articles about the fashionable show of the new flying machines, and Brod would take care to see that Kafka's text would be published by a Prague newspaper.

IMMEDIATELY AFTER they arrived at Brescia, our friends were surrounded by a noisy crowd and found a rickety carriage that could hardly move on its wheels but whose coachman was in a good mood and rushed them, through nearly empty streets, to the Komitepalast (actually, the Palazzo Bettoni, via Umberto I), where they were given the address of an inn that, at first sight, was the "dirtiest" they had ever seen. Kafka hated dirt viscerally, but he noted that the gesticulating innkeeper, "proud in himself, humble to us," constantly moved his elbows, "every finger a compliment." He ultimately resigned himself to ambivalent feelings of rage, dismay, and irony: "Who, one could ask, would have had the courage not to feel sorry in his heart for such dirt?" In a lighter moment, which Kafka remembered six years later in his diaries, on 4 November 1915, he walked on the Brescia cobblestones distributing a few soldi to the street kids (still in daylight), but as soon as the friends hired another horsecab, they ran into trouble and the evening was nearly ruined. Kafka did not say where he and his friends wanted to go, but to judge from their habits, it possibly was a café chantant, if not amore disreputable place. The driver asked for three lire, the friends offered two, but the driver did not want to go, dramatically describing the terrible distance he would have to cover. The friends agreed to pay three lire, and after one or two turns, they arrived. Otto promptly refused to pay three lire for a one-minute trip, argued loudly with the driver, and wanted to call the police unless he was shown "the tariff." The driver produced a smudged piece of paper with illegible numbers. The tourists had been had; Otto, still screaming, made an offer of one and a half lire (accepted), the driver galloped with his cab off into the next narrow street, where, however, he could not turn around, and Kafka realized the coachman was not only enraged but melancholy as well. The friends had not behaved appropriately, and Kafka remarked ruefully, "You cannot behave like this in Italy. Perhaps somewhere it may have been right, but not in Italy." Yet again, he added cheerfully, you cannot become an Italian so quickly, within the short week of an air show.Our friends spent a dreadful night at the dirty inn--"the robbers' cave," as they called it--and Max discovered, or later ...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherFarrar, Straus and Giroux

- Publication date2002

- ISBN 10 0374102597

- ISBN 13 9780374102593

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages272

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Air Show at Brescia, 1909

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. Seller Inventory # 0374102597-2-1

The Air Show at Brescia, 1909

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0374102597

The Air Show at Brescia, 1909

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon0374102597

The Air Show at Brescia, 1909

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0374102597

The Air Show at Brescia, 1909

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Brand New!. Seller Inventory # VIB0374102597

The Air Show at Brescia, 1909

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0374102597

The Air Show at Brescia, 1909

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0374102597

The Air Show at Brescia, 1909

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new0374102597

THE AIR SHOW AT BRESCIA, 1909

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.87. Seller Inventory # Q-0374102597