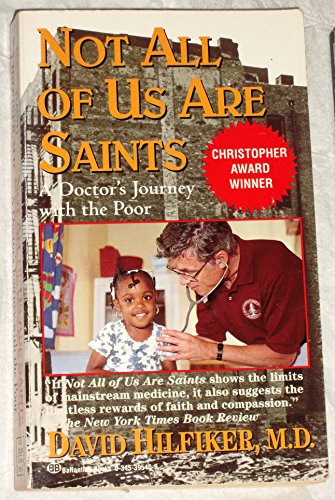

Not All of Us Are Saints - Softcover

In 1983, Dr. David Hilfiker left his practice in rural Minnesota and began to practice poverty medicine in a ravaged community not far from the White House. Fascinating and deeply affecting, this is his elegantly written true story of that time. Previously published by Hill and Wang.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

David Hilfiker, M.D., is the author of Not All of Us Are Saints.

Not All of Us Are Saints

Chapter 1 A DOCTOR'S JOURNEY This is absurd! What am I doing, near midnight, chasing John Turnell down the middle of Sixteenth Street? He's raving, swearing, pushing me away. What am I, a white man in white doctor clothes, doing entreating this drunken black homeless man to come home with me out of the night? It was in October 1983 that John Turnell was first brought in from the streets. He could hardly walk. Buried in a dark, matted coat, pants reeking of urine, eyes cast on the floor, he sat passively in the corner of the examining room at Community of Hope Health Services. "I hurt all over," he mumbled, barely audible. "My neck, my arm, my back, my leg. They're all achin'. My foot won't do nothin'." He glanced up and our eyes met briefly. "I'm alcoholic," he said. "But I ain't had nothin' to drink in four days." He looked away. "Gotta stop these shakes. I know I gotta stop drinkin' this time. It's killin' me." He paused and I searched for something to say. But he began again, almost in a whisper. "And I'm pissin' all over myself,too. I can't stop it ..." He hung his head. There was no expectation of help. He was simply reporting. Thirty-eight then, he had jumped from a burning building six years earlier, breaking his back. "Pained ever since," he said. He'd been hospitalized for surgery but got no relief from his suffering. I examined him. The pain, weakness, paralysis, and sensory loss from his broken back and the concomitant nerve damage were widespread. His left foot dragged, and the large thigh muscles of his left leg had atrophied. The nerves to his bladder were injured, so urine leaked all over his clothing. He had lost sensation in his buttocks and could not feel the large ulcers developing there that now drained constantly. He didn't have medical coverage, but the private hospital at which I had privileges allowed me to admit an occasional indigent patient for further examination. In the end, though, there was not much to be done. Further surgery was not recommended; long-term physical therapy would probably have been of some help, but there was no way to pay for it; the neurological damage--loss of sensation, constant pain, foot drop, weakness, incontinence, impotence--was permanent. For the next several months, I saw John every week in the clinic as I tended his ulcers. He stayed at a small shelter in the neighborhood. His pain never really went away, but--if he slept on a real bed and took pain medication regularly--he could keep it under control. He got used to wearing a leg bag for his urine. We found a foot brace so he could walk without a limp. "It don't bother me so much anymore," he said to me one day when I asked how he was getting along. "You get used to it. I walk okay with the brace, and at least I ain't pissin' all over. As long as I stay sober, anyway," and he grinned. I would see that grin again. It was big and bright, inviting, without a trace of resentment. And there was a certain sparkle in the eyes that looked directly into mine. He seemed to accept his woundswithout anger or resignation. I sometimes wondered how that was possible. Why didn't he just give up the fight? No, I exaggerate: He did not accept all his wounds ... not his impotence. "You know what it's like?" he would say. "You know how she looks at you? She never says nothin', never gets mad. She says it don't make no difference to her, but when she's ready, no woman's gonna stay around for a man who can't perform." We once had a urologist ready to evaluate John's impotence, to look for something that could be done, but there was no insurance for the in-hospital tests, and the evaluation was put on hold ... indefinitely, it turned out. As John got better, the shamefaced, bedraggled derelict who came into my office every Thursday evening was gradually replaced by a handsome man with an engaging style. He looked me in the eye, smiled, made little jokes. He thanked me "for all you've done." I began to hope for his future. Abandoned as a child, alcoholic since adolescence, homeless for years, even he started to talk about a future. He got a custodial job nights, running a waxing machine. But then, a few weeks later, he told me his back had started acting up and he had quit the job. At my urging and with the help of our social worker, he applied for disability coverage under the Supplemental Security Program (SSI) of the federal Social Security Act, but he was not enthusiastic. He wanted to work, he said, not live off welfare. Then, suddenly, John disappeared. I heard he was on the streets again. Several months later, his SSI disability claim was denied; the form letter said John was not sufficiently incapacitated. A volunteer lawyer associated with our clinic began an appeal, but John needed to appear in person, and no one knew where he was. The deadline passed. When, after eight months, John finally showed up again at the clinic, I hardly recognized him. He was unshaven, gaunt; his lusterless eyes sagged in a hollow face. He moved slowly, agonizingly.Light reflected off the spittle in his beard. Sitting in the chair opposite me, he looked much smaller than his six feet. His dark, oversized clothes stank of urine, and his eyes remained fixed on the ground in visible shame. Although sober that evening, he had, he told me, started drinking again shortly after leaving his job waxing floors. Sleeping in alleys, stairwells, and crowded shelters, he had aggravated his back pain, broken open the ulcers on his buttocks, and lost both leg bag and foot brace. Like a perverse safety alarm, however, the increasing pain had put an end to the drinking and goaded him into the clinic, embarrassed and repentant. I did not guess then how often this pattern was to repeat itself. We saw each other irregularly. He was always sober by the time he showed up at the clinic. The pattern became unmistakable: He would begin to feel good about himself, find a job, only to leave it after a few weeks (often because it aggravated his back), and then disappear into the streets and the alcohol. Invariably, as he got closer to independence, some inner compulsion would shatter his dream. As I watched him try to work while in severe pain, as I noticed the cycle that always ended in the streets, I began to encourage him not to work, to accept his disability. He, however, was impatient. I tried again to help him get SSI (which would at least allow him access to Medicaid and decent medical care), but the examiners turned him down once more. One autumn, three years after our initial meeting, John returned, and I convinced him to move into Christ House, the medical recovery shelter for homeless men that a group of us had recently established with the help of our church community. Better equipped and more intensively staffed than the other shelters, dedicated exclusively to the care of those who were too sick to be on the streets, Christ House was also my home, where our family lived with a small community of physicians, other staff people, and their families. Over many months with us, John maintained his sobriety, went through a twenty-eight-day, inpatient alcohol treatment program, attended Alcoholics Anonymous meetings daily, healed his buttock ulcers,strengthened his foot, began managing his incontinence with special medications, and was able to keep even the constant pain to a tolerable level. He began attending classes at my wife Marja's small adult education school, looking to get his high-school-equivalency diploma. I allowed myself to hope again. "I know it now: I just can't drink anymore, David ... ever. It's killin' me. I'm alcoholic. I didn't like it when you sent me to that treatment program, but I understand now. I got to stay away from my friends on the street who drink. Got to get new friends. Y'all have helped me so much here, and I'm gonna make it this time. God has been good. You'll see. I'll get my GED, get a job, maybe get married. I'm gonna make it." John "graduated" to a group home, continued attending GED classes with Marja, and was looking for work. Marja gave him one of our old family bicycles, so he could get around town. I felt proud of him. Then, once again, he disappeared. Two weeks later I was at the clinic when Sister Lenora Benda, the nurse in charge at Christ House, called. "John's back, David. He's been drinking, and he seems pretty depressed. He says he tried to swerve his bicycle into the path of a bus this morning, but the bus stopped. He keeps saying he wants to kill himself." I sigh and am silent. Some small part of me is dying. I knew enough to expect it, to prepare for it, but I'm still not ready. Drunk again, and now suicidal! Is this real or some bizarre gesture? Where in this city will I find a psychiatrist to evaluate a homeless drunk? Even if we can get him help, will he get something more than the superficial consultation to which the homeless are so often limited? "Can you get him over to St. Elizabeth's for a psychiatric evaluation, Lenora?" "I think so. I think he still trusts me enough to let me take him." Lenora manages to thread John through the system--an accomplishment in itself--and, that same afternoon, a psychiatrist at St. Elizabeth's, Washington's only public psychiatric hospital, evaluates John. The psychiatrist declines to hospitalize him, however, becausethe suicide attempt seems to her most likely to have been just a gesture brought on by his intoxication. John is released with instructions to make an appointment with me at the office. The next evening, as I am lecturing to family physicians at their local professional association about the health care needs of the homeless in our city, the shrill signal of my pager interrupts. It seems that John has returned to Christ House and is uncontrollable. He's been marching back and forth, in and out of Christ House, lying down in front of traffic in Columbia Road or yelling and creating havoc ins...

Chapter 1 A DOCTOR'S JOURNEY This is absurd! What am I doing, near midnight, chasing John Turnell down the middle of Sixteenth Street? He's raving, swearing, pushing me away. What am I, a white man in white doctor clothes, doing entreating this drunken black homeless man to come home with me out of the night? It was in October 1983 that John Turnell was first brought in from the streets. He could hardly walk. Buried in a dark, matted coat, pants reeking of urine, eyes cast on the floor, he sat passively in the corner of the examining room at Community of Hope Health Services. "I hurt all over," he mumbled, barely audible. "My neck, my arm, my back, my leg. They're all achin'. My foot won't do nothin'." He glanced up and our eyes met briefly. "I'm alcoholic," he said. "But I ain't had nothin' to drink in four days." He looked away. "Gotta stop these shakes. I know I gotta stop drinkin' this time. It's killin' me." He paused and I searched for something to say. But he began again, almost in a whisper. "And I'm pissin' all over myself,too. I can't stop it ..." He hung his head. There was no expectation of help. He was simply reporting. Thirty-eight then, he had jumped from a burning building six years earlier, breaking his back. "Pained ever since," he said. He'd been hospitalized for surgery but got no relief from his suffering. I examined him. The pain, weakness, paralysis, and sensory loss from his broken back and the concomitant nerve damage were widespread. His left foot dragged, and the large thigh muscles of his left leg had atrophied. The nerves to his bladder were injured, so urine leaked all over his clothing. He had lost sensation in his buttocks and could not feel the large ulcers developing there that now drained constantly. He didn't have medical coverage, but the private hospital at which I had privileges allowed me to admit an occasional indigent patient for further examination. In the end, though, there was not much to be done. Further surgery was not recommended; long-term physical therapy would probably have been of some help, but there was no way to pay for it; the neurological damage--loss of sensation, constant pain, foot drop, weakness, incontinence, impotence--was permanent. For the next several months, I saw John every week in the clinic as I tended his ulcers. He stayed at a small shelter in the neighborhood. His pain never really went away, but--if he slept on a real bed and took pain medication regularly--he could keep it under control. He got used to wearing a leg bag for his urine. We found a foot brace so he could walk without a limp. "It don't bother me so much anymore," he said to me one day when I asked how he was getting along. "You get used to it. I walk okay with the brace, and at least I ain't pissin' all over. As long as I stay sober, anyway," and he grinned. I would see that grin again. It was big and bright, inviting, without a trace of resentment. And there was a certain sparkle in the eyes that looked directly into mine. He seemed to accept his woundswithout anger or resignation. I sometimes wondered how that was possible. Why didn't he just give up the fight? No, I exaggerate: He did not accept all his wounds ... not his impotence. "You know what it's like?" he would say. "You know how she looks at you? She never says nothin', never gets mad. She says it don't make no difference to her, but when she's ready, no woman's gonna stay around for a man who can't perform." We once had a urologist ready to evaluate John's impotence, to look for something that could be done, but there was no insurance for the in-hospital tests, and the evaluation was put on hold ... indefinitely, it turned out. As John got better, the shamefaced, bedraggled derelict who came into my office every Thursday evening was gradually replaced by a handsome man with an engaging style. He looked me in the eye, smiled, made little jokes. He thanked me "for all you've done." I began to hope for his future. Abandoned as a child, alcoholic since adolescence, homeless for years, even he started to talk about a future. He got a custodial job nights, running a waxing machine. But then, a few weeks later, he told me his back had started acting up and he had quit the job. At my urging and with the help of our social worker, he applied for disability coverage under the Supplemental Security Program (SSI) of the federal Social Security Act, but he was not enthusiastic. He wanted to work, he said, not live off welfare. Then, suddenly, John disappeared. I heard he was on the streets again. Several months later, his SSI disability claim was denied; the form letter said John was not sufficiently incapacitated. A volunteer lawyer associated with our clinic began an appeal, but John needed to appear in person, and no one knew where he was. The deadline passed. When, after eight months, John finally showed up again at the clinic, I hardly recognized him. He was unshaven, gaunt; his lusterless eyes sagged in a hollow face. He moved slowly, agonizingly.Light reflected off the spittle in his beard. Sitting in the chair opposite me, he looked much smaller than his six feet. His dark, oversized clothes stank of urine, and his eyes remained fixed on the ground in visible shame. Although sober that evening, he had, he told me, started drinking again shortly after leaving his job waxing floors. Sleeping in alleys, stairwells, and crowded shelters, he had aggravated his back pain, broken open the ulcers on his buttocks, and lost both leg bag and foot brace. Like a perverse safety alarm, however, the increasing pain had put an end to the drinking and goaded him into the clinic, embarrassed and repentant. I did not guess then how often this pattern was to repeat itself. We saw each other irregularly. He was always sober by the time he showed up at the clinic. The pattern became unmistakable: He would begin to feel good about himself, find a job, only to leave it after a few weeks (often because it aggravated his back), and then disappear into the streets and the alcohol. Invariably, as he got closer to independence, some inner compulsion would shatter his dream. As I watched him try to work while in severe pain, as I noticed the cycle that always ended in the streets, I began to encourage him not to work, to accept his disability. He, however, was impatient. I tried again to help him get SSI (which would at least allow him access to Medicaid and decent medical care), but the examiners turned him down once more. One autumn, three years after our initial meeting, John returned, and I convinced him to move into Christ House, the medical recovery shelter for homeless men that a group of us had recently established with the help of our church community. Better equipped and more intensively staffed than the other shelters, dedicated exclusively to the care of those who were too sick to be on the streets, Christ House was also my home, where our family lived with a small community of physicians, other staff people, and their families. Over many months with us, John maintained his sobriety, went through a twenty-eight-day, inpatient alcohol treatment program, attended Alcoholics Anonymous meetings daily, healed his buttock ulcers,strengthened his foot, began managing his incontinence with special medications, and was able to keep even the constant pain to a tolerable level. He began attending classes at my wife Marja's small adult education school, looking to get his high-school-equivalency diploma. I allowed myself to hope again. "I know it now: I just can't drink anymore, David ... ever. It's killin' me. I'm alcoholic. I didn't like it when you sent me to that treatment program, but I understand now. I got to stay away from my friends on the street who drink. Got to get new friends. Y'all have helped me so much here, and I'm gonna make it this time. God has been good. You'll see. I'll get my GED, get a job, maybe get married. I'm gonna make it." John "graduated" to a group home, continued attending GED classes with Marja, and was looking for work. Marja gave him one of our old family bicycles, so he could get around town. I felt proud of him. Then, once again, he disappeared. Two weeks later I was at the clinic when Sister Lenora Benda, the nurse in charge at Christ House, called. "John's back, David. He's been drinking, and he seems pretty depressed. He says he tried to swerve his bicycle into the path of a bus this morning, but the bus stopped. He keeps saying he wants to kill himself." I sigh and am silent. Some small part of me is dying. I knew enough to expect it, to prepare for it, but I'm still not ready. Drunk again, and now suicidal! Is this real or some bizarre gesture? Where in this city will I find a psychiatrist to evaluate a homeless drunk? Even if we can get him help, will he get something more than the superficial consultation to which the homeless are so often limited? "Can you get him over to St. Elizabeth's for a psychiatric evaluation, Lenora?" "I think so. I think he still trusts me enough to let me take him." Lenora manages to thread John through the system--an accomplishment in itself--and, that same afternoon, a psychiatrist at St. Elizabeth's, Washington's only public psychiatric hospital, evaluates John. The psychiatrist declines to hospitalize him, however, becausethe suicide attempt seems to her most likely to have been just a gesture brought on by his intoxication. John is released with instructions to make an appointment with me at the office. The next evening, as I am lecturing to family physicians at their local professional association about the health care needs of the homeless in our city, the shrill signal of my pager interrupts. It seems that John has returned to Christ House and is uncontrollable. He's been marching back and forth, in and out of Christ House, lying down in front of traffic in Columbia Road or yelling and creating havoc ins...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherBallantine Books

- Publication date1996

- ISBN 10 0345395409

- ISBN 13 9780345395405

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages258

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 96.45

Shipping:

US$ 4.13

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

NOT ALL OF US ARE SAINTS

Published by

Ballantine Books

(1996)

ISBN 10: 0345395409

ISBN 13: 9780345395405

New

Softcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.3. Seller Inventory # Q-0345395409

Buy New

US$ 96.45

Convert currency

Not All of Us Are Saints

Published by

Ballantine Books

(1996)

ISBN 10: 0345395409

ISBN 13: 9780345395405

New

Mass Market Paperback

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Mass Market Paperback. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks2481

Buy New

US$ 300.00

Convert currency