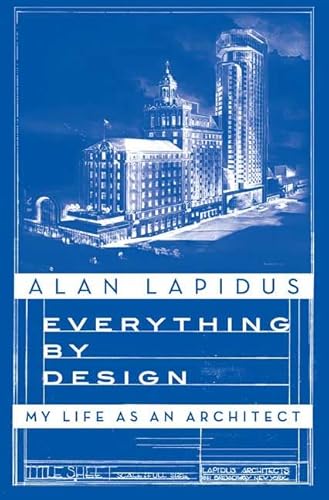

Everything by Design: My Life as an Architect - Hardcover

Everything by Design takes us behind the scenes in Las Vegas, Disney World, Havana, Atlantic City, Moscow, the Amazon rainforest, and New York. Along the way we learn why Mickey Mouse never seems to use the restroom, why the baccarat tables in casinos are always far away from the dice tables, why the CIA wanted him to redesign Havana's main synagogue, and why the tunnels under the Hotel Moskva can't be touched.

Everything by Design is a keenly observed social and cultural history of modern America by one of its key shapers.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

1.Donald Trump's ArchitectThe voice on the phone had a tone of easy familiarity: "Hey, Alan, howyadoin', it's been a while."It had indeed been a while since I last talked to Donald Trump. His call would lead to me becoming "Donald Trump's Architect," to quote The Wall Street Journal, and being intimately involved in the design and construction of Trump Plaza, his first casino in Atlantic City or, for that matter, his first anywhere. It amounted to my having the opportunity to see Donald in action before he was The Donald, to watch him evolve from his first persona into his second, like a moth into a butterfly. Or, perhaps more to the point, from a run-of-the-mill butterfly into a spectacular creature.During the late 1950s, a man named Fred Trump vacationed at one of my father's early and smaller Miami Beach hotels, the Sans Souci. Trump fell in love with the design of the lobby. He felt that if he added a "classy" lobby to the otherwise drab middle-income high-rise apartments he was planning to build on Ocean Parkway in Brooklyn (still known as Trump Village), he could beat the competition. Trump called our office, only to have Morris turn him down cold: "I don't do lobbies!"Fred Trump was a man who got what he wanted--a family trait his son Donald inherited and of course perfected. This apartment complex was to contain more than three thousand units, and if Morris would design the lobby, well, then Fred would hire him as architect for thewhole complex. It was an offer my father couldn't refuse. Fred specified that the structures were being built under a federally subsidized housing program, meaning that by necessity and regulation, they had to be plain boxes with punched windows. We could choose any brick we wanted, as long as it was red, unglazed Hudson Valley brick. But the lobbies--they would be terrific! And the generous fees for such bland and mindless work were irresistible. Trump Village was a smash hit, immediately filled with eager renters and later successfully converted to condos.At that time I was just starting to work in the firm, and I occasionally accompanied Morris on his site visits, where we encountered Fred Trump. Fred was tall and lean, with high cheekbones and piercing eyes set in an angular face. He was gruff and yet very likable at the same time. He had a relatively modest office on Avenue Z in Brooklyn (our home had been on Avenue J), and it reflected his down-to-earth, outer-borough persona: The sole decoration in the place was a large wooden cigar store Indian.Fred believed in maintaining political connections and using them to access programs that subsidized the production of sensible, solid apartments for working-class people. He also believed in avoiding anything having to do with Manhattan--a trait his son would not share, of course. It was during one of these visits that Fred introduced me to one of his sons, a cocky fourteen-year-old lad ten years my junior with sandy blond hair and a round face. The kid, who was watering down a pile of dusty construction rubble, was Donald. During the early stages of my relationship with the Trump family, I became friendly not with Donald but with his older brother, Fred Jr., a pilot for American Airlines. Since I was a newly minted pilot, he and I talked flying, not real estate.Many years later, in the early 1980s, the grown-up Donald acquired a parcel on Atlantic City's Boardwalk, next to the Convention Hall, a site that I had worked on for another developer who had been unable to secure funding. But Donald had gone my former client one step better by assembling the rest of the block. Having seen my name on the plans for the initial attempt, he learned that I had already designed two other Atlantic City casinos that had won full approvals and that I was very much involved in the whole scene there. I of course had been following his meteoric rise in Manhattan real estate circles.Now he spoke to me as an old family friend. Explaining that he hadbecome owner of the site and seen my work, he felt it would be ideal for us two old "buddies" to work together. After all, we were both second generation, and each of us was going to show his father a thing or two. And, by the way, he added, because we were practically "family," I couldn't charge him the fancy fees that I charged my other clients.I was charmed.Donald had put together several notable packages by then, but he had never been the sole principal. One such deal was the Grand Hyatt Hotel, which he created out of the old Commodore, in a brilliant piece of brinkmanship. During the mid-1970s, New York City was on the verge of bankruptcy, thanks in part to the ineptitude of his father's old political cronies, and Forty-second Street was starting to look like a thirdworld thoroughfare. The boarded-up Commodore Hotel, once one of the city's finest, was now a deserted eyesore that greeted passengers leaving Grand Central Station. Public confidence in the city had reached an all-time low.Donald walked the neighborhood and noticed that on the opposite side of Forty-second was the headquarters of the Dime Savings Bank. Never afraid to go fishing in troubled waters, he brashly informed Dime executives that the value of their real estate was down the tubes, facing the derelict Commodore as it was. But, he promised, if they backed him he would transform their location from a quickly devaluating pit into the centerpiece of the city's renaissance. They bought into the idea. Trump eventually was able to win spectacular concessions from a desperate municipality, and even better terms from the state. The reborn hotel, the Grand Hyatt, did indeed accomplish all that Donald had promised. It was the shot in the arm the city needed, a sign that someone was still willing to bet that there was a future. In the annals of municipal chutzpah, if not municipal planning, it was pure genius. But it was the state's superagency, the Empire State Development Corporation, not Donald Trump, that actually owned the building. That arrangement was a necessary formality in order to obtain state subsidies, but it was Donald who made the big bucks. Likewise, Trump Tower, another thoroughly audacious development, was done under the aegis of the Equitable Insurance Company.By the time he approached me about his Atlantic City property, Donald hungered for a deal that would be his very own. When I asked whyhe was planning to do a development in Atlantic City, since all his financial and political connections were in New York City, his reply was the same as the one given by noted bank robber Willie Sutton when asked why he robbed banks: "That's where the money is."Donald and I made a date to go down to A.C., and I offered to fly him in my airplane. This was before the days of his private jets, helicopters, and yachts, and he was delighted. My airplane was a solid, reliable, single-engine propeller craft, which, although mechanically perfect, left something to be desired in the cosmetics department. We met at Teterborough Airport, my home base, and headed south. Donald sat next to me in the right seat, and his COO, Harvey Freeman, sat in back working on The New York Times crossword puzzle. Donald chattered away as we flew down the Atlantic coast. Navigating from the outskirts of New York City to A.C. is quite simple: Fly to nearest ocean, turn right, keep going until you see a bunch of high-rise buildings, land. So his conversation didn't distract me at all. In the midst of talking, he became aware of the less than pristine upholstery, then looked over at me and inquired, "Hey, Alan, is this plane safe?"My reply amused him: "Donald, my epitaph is not going to be 'Donald Trump and two others die in plane crash.'"

As the months went by, I began to fully appreciate why Donald was such a force to be reckoned with. He was street smart in a way that distinguished him from other developers I had worked with. Donald was a young WASP in a field dominated by aged Jews. Not just Jews, but German Jews. New York's real estate dynasties were not founded by turn-of-the-century immigrants from Eastern Europe. That group landed on our shores for the most part religious, penniless, and, except for their Hebrew education, illiterate. The German Jews had arrived much earlier and were mostly coming to something rather than fleeing from something. Polished and urbane, they and their descendants used their education and drive to found enduring businesses. The Tishmans, the Zeckendorfs, and the Silversteins (all my clients or to be my clients) were prime examples. In his book Our Crowd, Stephen Birmingham did a brilliant study of these folks. Temple Emanu-El, the temple of this set, was such an Episcopalwannabe that for a long time few if any bar mitzvahs (disdained as a trashy Eastern European custom) were performed there. A standing joke, at least among all of us "Johnny-come-lately" Jews, was that at Temple Emanu-El they were so WASP that they were closed on Shabbos (the Jewish Sabbath).At that time, the established real estate guys kept an extremely low profile. Relatively unknown to the public, they wanted to maintain their ability to fly below the radar and generally avoided publicity. The reason was straightforward: Big real estate deals were dependent on the proper political allies. There were government subsidy programs, subtle shifts of zoning entitlements, and myriad other ways that a politician could smooth the path of a real estate transaction. Bear in mind that during this era before Watergate and "open government," meaningful public forums, rights of disclosure, and investigative reporters were comparatively rare; the fabled "smoke-filled back rooms" were no fable.Then along came this kid from Queens who had been raised by a low-key, in fact damn near invisible, WASP developer of a father and steeped in the timeless tradition of political patronage and rock-solid developer smarts. Young Donald Trump was brash, smart, driven, and, above all, clever. He did not give a fiddler's fart for the aloof old boys' world of Manhattan developers. He had a feel for the times he lived in. He knew that his future customers would have the same sensibilities he did. Donald instinctively understood that regardless of how much people professed admiration for "culture" and the refined taste of the ads in The New Yorker, what they really wanted was glitz and glamour.At least his market did. And, as history has shown, his market is quite large.The old guard reacted with loathing and derision. Harry Helmsley, one of the leading Manhattan developers, was publicly scornful: "The kid can talk, but he can't build." Ironically, Helmsley's own membership in the old guard was threatened during the years before his death in 1997, as he became somewhat marginalized socially after his 1972 marriage to Leona Helmsley, "the Queen of Mean." I met her at a couple of social occasions and found it easy to see why she was so widely disliked.Donald was really the first to grasp the sea change in how Americans bought real estate. It wasn't only about getting solid value for yourmoney--it was also about celebrity. He understood that if he made himself a star or, in our world of hyperbole, a superstar, he could enhance the value of anything he had to sell, including himself. Circular logic, perhaps, but, oh, so true!Years later, when he owned three Atlantic City casinos, Trump's enterprises did quite well because people wanted to associate with a star, hoping some of the glamour would rub off on them. I once walked with him across the gaming floor of his Taj Mahal, watching in amazement as hordes literally flocked around him, hoping to be acknowledged as they heaped adulation upon his meticulously coiffed head. As the two of us moved along, Donald with his signature black cashmere overcoat draped over his shoulders like an Italian movie director, and I practically invisible, I realized that for him it was a case of mission accomplished.Yes, Donald had actually succeeded in turning his name into a brand!By sheer coincidence, I had two groups of clients named Trump during the mid-1980s. One pair was Donald and his brother Robert. The other pair, unrelated to Donald and Robert, was a Jewish brother duo named Julius and Eddie Trump. Each team of brothers was developing real estate on a grand scale. Moreover, their Manhattan offices were a scant half block apart; the offices of Julius and Eddie were at 9 West Fifty-seventh, while Donald's headquarters were at Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue between Fifty-sixth and Fifty-seventh. Julius and Eddie were building a complex in north Miami Beach called Williams Island. Full-page ads for this venture appeared frequently in The New York Times, stating that it was a project of the Trump Group.The result was almost inevitable: Donald sued Julius and Eddie for using his name. To be sure, Julius and Eddie, in contrast to Donald, were Orthodox Jews of South African descent; their name was either Afrikaner or Dutch and had been theirs for many generations.Donald won.All of Julius and Eddie's subsequent advertising had to display the disclaimer that they were not a part of the Trump Organization. Donald, aware that I was architect for the other Trumps as well, confided in me, "Hell, if I liked their stuff I would claim it was my project, but it's too low-class for my name."Donald was also quick to grasp the idea that if you embellished a storyenough times, loudly enough, and with squinty eye and furrowed brow, and if you had the best publicist in New York (Howard Rubenstein) to make sure you were quoted in the popular press almost daily--all the while repeatedly denying that you had a publicist--you were whatever you said you were. Truth was a self-fulfilling prophecy. As the Cary Grant character, an ad executive in one of my favorite movies, North by Northwest, declared, "In the world of advertising, there's no such thing as a lie. There's only expedient exaggeration."The same holds true in real estate, and condemning a real estate developer for exaggeration, hyperbole, and even outright lies is like condemning a fish for swimming. Such is the nature of the business--as it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be. That's how Atlantic City started as a resort, created by developers using absurd claims from medical doctors about the ability of Absecon Island's sea breezes to cure everything from cancer to dropsy. Likewise, America's West was settled by pioneers lured to the frontier by developers and land salesmen claiming that the cold, dangerous, and forbidding prairie was the Garden of Eden. Compared to those statements and countless other similar ones, Donald's claims seem modest indeed.

A developer's objective is to sell what he or she develops. You don't have to be a rocket scientist to understand that that's how developers make their money, often tons of money. Developers are not in the business of improving the human condition or elevating the masses. The biggest difference between Donald Trump and other developers is that Donald has carried the business to its logical conclusion. If his name is on a project, it sells; he has literally and officially morphed into a franchise. He may not quite be McDonald's, but many of his most recent deals do amount to him "selling" his name to other people's developments for millions of dollars and a cut of the take. He doesn't own, and never has owned, the Trump International Hotel, Trump Place, and other big "T" icons. His lucrative type of no-investment, n...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherSt. Martin's Press

- Publication date2007

- ISBN 10 0312361661

- ISBN 13 9780312361662

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages320

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 3.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Everything by Design: My Life as an Architect

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new0312361661

Everything by Design: My Life as an Architect

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. In shrink wrap. Seller Inventory # 100-09253

Everything by Design: My Life as an Architect

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0312361661

Everything by Design: My Life as an Architect

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks52717

Everything by Design: My Life As an Architect

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: Brand New. 288 pages. 9.50x6.75x1.00 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # 0312361661

EVERYTHING BY DESIGN: MY LIFE AS

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.2. Seller Inventory # Q-0312361661