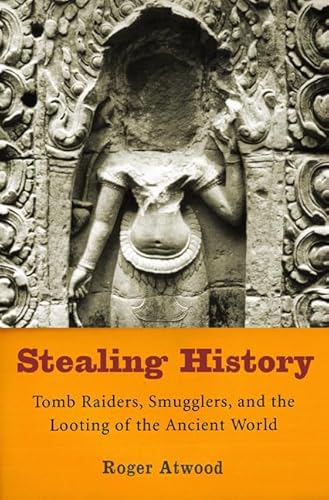

Stealing History: Tomb Raiders, Smugglers, and the Looting of the Ancient World - Hardcover

Roger Atwood knows more about the market for ancient objects than almost anyone. He knows where priceless antiquities are buried, who is digging them up, and who is fencing and buying them. In this fascinating book, Atwood takes readers on a journey through Iraq, Peru, Hong Kong, and across America, showing how the worldwide antiquities trade is destroying what's left of the ancient sites before archaeologists can reach them, and thus erasing their historical significance. And it is getting worse. The discovery of the legendary Royal Tombs of Sipan in Peru started an epidemic. Grave robbers scouring the courntryside for tombs--and finding them. Atwood recounts the incredible story of the biggest piece of gold ever found in the Americas, a 2,000-year-old, three-pound masterpiece that cost one looter his life, sent two smugglers to jail, and wrecked lives from Panama to Pennsylvainia. Packed with true stories, this book not only reveals what has been found, but at what cost to both human life and history.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Roger Atwood is a regular contributor to ARTnews and Archaeology magazines, and his articles on culture and politics have appeared in The New Republic, Mother Jones, The Nation, The Miami Herald, and The Boston Globe. Atwood was a journalist for Reuters for over fifteen years, reporting from Peru, Argentina, Brazil, and Chile, and a senior editor at their Washington, D.C. bureau. He is currently a fellow at the Alicia Patterson Foundation.

PART ONEChapter 1LOOKING FOR A TOMBWE SAT UNDER a tree in the moonlight chewing coca leaves, a heap of shovels and metal poles resting on the ground next to us. We chased down the coca's weedy taste with cane liquor known as llonque and talked in whispers so as not to awaken dogs at the adobe farmhouses across these fields on the south coast of Peru, where workers slept after a day harvesting cotton. Waves washing onto the beach a few miles away sounded like a distant sigh. A stone's throw in front of us, lying in the moonlight like a huge, slumbering animal, rose the pale burial pyramid built by the Incas five centuries ago which these three men were about to assault."La coca está dulce," said one. The coca is sweet. They will have luck tonight.They were huaqueros, a uniquely Peruvian word for a global phenonomenon, professional grave robbers. The leader of the group was known to everyone as Robin, a nickname he took from the Batman comics he liked as a boy and which stuck through his young, successful career digging up the remains of three millennia of history along the cool, arid coast of Peru. Robin did not know if it was luck or natural gift or a combination of the two, but he had developed a knack for finding the gorgeous textiles that ancient Peruvians wove, wore, and took to their graves. He had a sharp instinct for which of the thousands of eroded mud-brick burial pyramids, known as huacas in the indigenous language Quechua, would yield marketable artifacts and which only bones, worthless bits of ceramics, andtattered rags. Dealers and collectors contacted him because he found the good stuff: delicate, exquisitely designed weavings in a galaxy of colors that, centuries ago, were considered beautiful enough to accompany the dead to the underworld and today, for the very best ones, could fetch more than a Renoir or a Matisse.Wearing dark sweatpants and T-shirts, Robin and his buddies talked about strange and beautiful things they had found over the years--perfectly preserved pots, color-spangled weavings, piles of bones and skulls. Robin told of jars in the shape of animals, a clown, a corncob. Looting a tomb, the three of them once found an Inca weaving that bore a design of a condor with outstretched wings, directly facing the viewer with penetrating, human eyes. But when they picked it up, the weaving was so delicate it fell apart.1They talked about the fickle spirits of the dead that can bring them luck or frustration. The talked of the huaca as a living force with jealousies and resentments, moments of generosity and fits of spite."If you act greedy, the huaca won't give you anything. You take too much, and it will close up and never give you anything again," said Robin."Sometimes it helps you out, sometimes it won't give you anything. But it warns you. It speaks to you," said his friend Remi, a tall, narrow man with a grave air.At twenty-three, Robin had been digging up tombs almost every night since his early teens. He earned a little money on the side driving a taxi. He looked a lot like the boxer Oscar De La Hoya and had the body to go with it; looting kept him in great shape, he said."We're going to walk up the middle of the huaca, start at the top and work our way down. And keep your voice down," Robin whispered to me, as if discussing a military attack. I wore dark clothes, as instructed, and I knew the rules: pictures were allowed but no flash, and if you must talk, whisper. He had had some close calls but was never arrested, and he didn't want to start tonight.I met Robin through a veteran grave robber named Rigoberto, whom in turn I met through a friend of mine who collected antiquities in Lima. Robin and Rigoberto were neighbors in Pampa Libre, a village of a few hundred people north of Lima where the local economy had been based for generations on the looting of ancient burial grounds in the hills nearby. Those cemeteries, never rich to begin with, were yielding fewer and fewer treasures and so, having exhausted the community's principal source of revenue, its young men were forced to range further and further afield to meet the demands of their buyers. Carrying knapsacks and cell phones, they took buses up and down the coast and built up contacts with looters in other villages to form digging teams and split the proceeds. The huaqueros of Pampa Libre were known as businesslike, honest, and adaptable to anyplace and digging environment. Chimbote, Ica, Casma, Nazca, Arequipa-- they had worked everywhere. Rigoberto, now in his early forties, had developed strange lung ailments that no one could explain and his bones felt weak, so, at the urging of his teenaged son, he had given up grave robbing. He was reduced to selling ceramic pots to tourists in the streets of Lima.Robin, on the other hand, was still strong and enthusiastic, and he loved his job. "I dig whenever I get the chance," he told me. In four years in Peru, I couldn't remember meeting anyone so happy about his work. It took some persuading, but he agreed to let me come along with him and his buddies that evening.

To tell others about how the antiquities trade works at its source, you first have to see grave robbers in action. You must look deeply and unflinchingly down their holes, watch the violent and nauseating act of the living evicting the dead from their graves. You have to become a witness to a crime, and you have to risk arrest.Robin and I met that day on Jirón Leticia, a street in the center of Lima with a reputation for muggings and assaults. I walked past grimy mechanic shops, street vendors selling stolen radios and mirrors, taxis pushed up against the sidewalk with their hoods open, a man with his head in the engine and another on his back underneath. Robin stood on the corner waiting for me, a knapsack over his shoulders."So the pickpockets didn't get you. Good. Let's go," he said. We walked around a corner to a cavernous garage and boarded a bus whose engines chugged to life, and the bus drove out into the morning sun and headed south.The Pan-American Highway makes its way past tidy, middle-class neighborhoods and shopping centers, ramshackle districts of street stalls and half-finished cinderblock structures and shantytowns climbing the hillsides, before winding out into a landscape of sand dunes, billboards, and green irrigated fields, a jagged knife of mountains on the left and ocean on the right. The contrasts that define Peru are all around you, wealth juxtaposed with poverty, mountains with ocean, desert with farm.As we headed south, the ruins of the ancient shrine of Pachacamac appeared, a complex of mud-brick walls, terraces, and enclosures rising on a hillside above the coastal plain, a few tour buses parked nearby. Pachacamac was to pre-Conquest Peru what Delphi was to Greece or Santiago de Compostela to medieval Europe, a sacred shrine that drew pilgrims from all over the realm and the site of an idol whose oracular utterances were relayed to the crouching faithful by the altar's priests. The Incas told the first Spanish chroniclers in the 1500s that before being allowed to climb the shrine to its uppermost sanctuary and hear the idol speak, pilgrims weresupposed to have fasted for a year. No one can survive a year without eating, of course, but the point was that people endured a once-in-a-lifetime regime of privation and sacrifice before the oracle would deign to speak to them. What was so extraordinary about the Pachacamac cult was how long it lasted: some 1,300 years, through the rise and fall of successive indigenous Andean cultures and civilizations until the last of them, the Incas. Pilgrims were still fasting and trekking to Pachacamac from across the Andes when, in Tumbes in the far north of the Inca realm, the Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro landed on May 16, 1532, with a few hundred men and written permission from Queen Isabella of Spain to conquer the empire they knew lay to the south. Neither Pachacamac nor the Incas could survive the Spanish onslaught. The conquistador's brother, Hernando Pizarro, and his men marched into the sanctuary in January 1533, evicted the priests, threw the wooden idol to the ground, and spent a month ransacking the shrine's rooms and platforms in a fruitless search for gold.2"With greed and yearning they reached Pachacamac, where they had heard news that there would be great treasures," wrote the Spanish priest Fray Martín de Murúa in about 1590. After the conquerors left, "this memorable temple was deserted and uninhabited."3Robin pointed."No one has ever found anything at Pachacamac. All the huaqueros try, but there is nothing to find or it's so deep underground that we can't reach it," he said. "The first time we tried, the guards came over right away and chased us out. The second time it was at night, and we entered around the back side over by the pueblo joven (shantytown), and we started to sink our poles into the ground. We sank one, two, maybe three poles into the ground, and then the night guards came over and chased us away. Some of the guys went back and sank more poles into the ruins, but they never found a thing."Some huacas are bad. They don't give you anything.""What kinds of things are you looking for when you loot?" I asked."We don't look for ceramics anymore because they're hard to sell, except for the very best pieces. A really good pot can sell for $500 or so. But we don't get many orders for ceramics, I guess because too much of it entered the market at once," he said. "What people want these days is textiles and more textiles, or metalwork, although there isn't much metalwork in the places I work. So we look for textiles."His assessment of the market astonished me. It was almost identical to the one I heard from art dealers and collectors in pre-Columbian art in the United States: textiles currently drove the pre-Columbian antiquities market, fine metalwork also had a niche, and ceramics were definitely out after experiencing a long glut, though top-quality pottery still sold well. This looter, who had never finished high school, never set foot outside Peru orused a computer, was completely in tune with the demand side of the looting industry.We got off at Chilca, a sad, deracinated town of truckstops and half-finished houses jumbled out along the highway, a place best known to Peruvians as the frequent epicenter of earthquakes, built as it is on a geological pressure point that keeps the town in constant danger of being wiped from the earth at a single stroke. Robin led me through dusty lots and alleys to a small house that looked recently constructed of Eternit cinderblocks and corrugated-metal roofing. Inside were a few mismatched chairs on a dirt floor, a tattered poster with a calendar and a beer ad, a version of The Last Supper in dark velvet hanging over an uneven table. This was the home of Remi, Robin's best buddy in looting and a lanky man who, at twenty-one, still had an adolescent awkwardness. As he greeted us and tended a few chickens in the yard, I could tell Remi was nervous about meeting me. His uncle, a lifelong looter, had been arrested one night recently along with six others at an old Inca graveyard across the highway, where they had found many small weavings over the years. The police had come with a television crew, and under a harsh white TV spotlight, the police handcuffed and took them all to jail in the provincial capital of Cañete, where they languished for a few days until one of their buyers hired a lawyer to persuade (or perhaps bribe) a judge to release them. The buyer's motive was clear: he was losing his suppliers. Robin had been with Remi's uncle in the graveyard that night, but he and another looter managed to evade the police and walked all night to Pucusana, a village on the southern outskirts of Lima, one of the unlikely escapes that gave Robin his reputation as a master grave robber with a Houdini-like ability to dodge arrest. Remi was apprehensive about meeting another journalist. His uncle stayed in his little room off the chicken coop, refusing to emerge or let me see him.Soon the third looter came around, a deeply tanned man of twenty-five with a shy smile whose name was Luis, but everyone called him Harry after the Clint Eastwood character that he liked. Harry was born high in the Andes in the city of Huaraz. He ran away from home in his early teens because his father beat him and came to the coast where he fell in with the Pampa Libre people and had been busting into tombs every night since. That afternoon the four of us walked for miles out of town, past brick kilns the size of houses, soccer pitches, fig groves, and poultry barns, out to a desolate hill overlooking a wide, scallop-shaped bay dotted with fishing boats.People had once lived on this hill. As the huaqueros led me up, I could make out a network of mortarless stone walls with narrow lanes running between them, a kind of rough grid running over the crest. These walls had stood mostly undisturbed until about 1990, said Remi, who had lived in the area all his life."Then the huaqueros came," he said with a grin. Now the walls were inruins. Jawbones, pelvises, and skulls bleached by the sun lay everywhere, and gaping holes showed where the looters had scraped out tombs like backroom dentists pulling teeth. From the simple objects and ordinary textiles that they pulled from this hill, they deduced that it had been inhabited by Inca commoners. But if it had been a graveyard, a village, or something else, we would never know because this place, perhaps overlooked by archaeologists, looked like a tornado had come through. Looters did not return to the place now because there was nothing left. The tombs were all dug up, the place tapped out. It all happened very fast and very recently, in the last two decades of the twentieth century, a period that will be remembered as one in which more Andean historical heritage was lost than in the previous four centuries, a time when looting reached a fury never before seen in this country's long history of plunder.A few black vultures soared overhead, looking suddenly very close.Just before nine o'clock that evening, we flagged down a bus on the highway and clambered on. We drew a lot of stares, these three Peruvian workers and me, a thirty-nine-year-old foreigner, all carrying knapsacks and loads of shovels and poles, but no one said anything before we alighted at an empty stretch of highway a few miles north of Cañete and began walking silently through fields of corn and cotton. A dog barked somewhere in the darkness, but we encountered no one as we walked along and came finally to the big tree. For three hours we sat on its gnarled roots, sucking and spitting out quids of coca and sending rivers of cane liquor roaring down our throats. There are some five thousand known huacas on the coast of Peru, some as tall as ten-story buildings and holding the tombs of monarchs, others merely a hump in the landscape where commoners were buried. These looters had gone after hundreds of them. But this huaca they preferred above all others in the area because its tombs were close to the surface, there were few houses in the immediate vicinity, and not many other looters had discovered it yet. They had heard that good textiles could be found here.It was after midnight when they packed the plastic bottles, gathered the tools, and walked along a line of scrubby bushes t...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherSt. Martin's Press

- Publication date2004

- ISBN 10 0312324065

- ISBN 13 9780312324063

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages352

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Stealing History: Tomb Raiders, Smugglers, and the Looting of the Ancient World

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0312324065

Stealing History: Tomb Raiders, Smugglers, and the Looting of the Ancient World

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon0312324065

Stealing History: Tomb Raiders, Smugglers, and the Looting of the Ancient World

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new0312324065

Stealing History: Tomb Raiders, Smugglers, and the Looting of the Ancient World

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0312324065

Stealing History: Tomb Raiders, Smugglers, and the Looting of the Ancient World

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0312324065

Stealing History: Tomb Raiders, Smugglers, and the Looting of the Ancient World

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # mon0000013874

Stealing History: Tomb Raiders, Smugglers, and the Looting of the Ancient World

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0312324065

Stealing History: Tomb Raiders, Smugglers, and the Looting of the Ancient World

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. 1.46. Seller Inventory # 0312324065-2-1

Stealing History: Tomb Raiders, Smugglers, and the Looting of the Ancient World

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published 1.46. Seller Inventory # 353-0312324065-new

Stealing History: Tomb Raiders, Smugglers, and the Looting of the Ancient World

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks69863