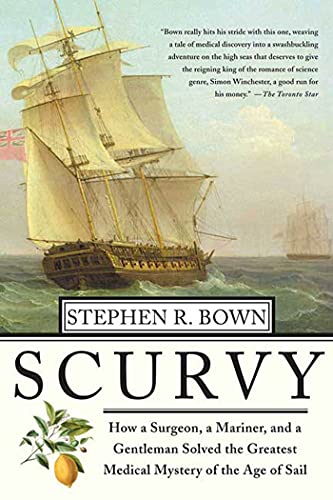

Scurvy: How a Surgeon, a Mariner, and a Gentlemen Solved the Greatest Medical Mystery of the Age of Sail - Softcover

Scurvy took a terrible toll in the Age of Sail, killing more sailors than were lost in all sea battles combined. The threat of the disease kept ships close to home and doomed those vessels that ventured too far from port. The willful ignorance of the royal medical elite, who endorsed ludicrous medical theories based on speculative research while ignoring the life-saving properties of citrus fruit, cost tens of thousands of lives and altered the course of many battles at sea. The cure for scurvy ranks among the greatest of human accomplishments, yet its impact on history has, until now, been largely ignored.

From the earliest recorded appearance of the disease in the sixteenth century, to the eighteenth century, where a man had only half a chance of surviving the scourge, to the early nineteenth century, when the British conquered scurvy and successfully blockaded the French and defeated Napoleon, Scurvy is a medical detective story for the ages, the fascinating true story of how James Lind (the surgeon), James Cook (the mariner), and Gilbert Blane (the gentleman) worked separately to eliminate the dreaded affliction.

Scurvy is an evocative journey back to the era of wooden ships and sails, when the disease infiltrated every aspect of seafaring life: press gangs "recruit" mariners on the way home from a late night at the pub; a terrible voyage in search of riches ends with a hobbled fleet and half the crew heaved overboard; Cook majestically travels the South Seas but suffers an unimaginable fate. Brimming with tales of ships, sailors, and baffling bureaucracy, Scurvy is a rare mix of compelling history and classic adventure story.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

STEPHEN R. BOWN was born in Ottawa and graduated in history from the University of Alberta. He has a special interest in the history of science and exploration. His books include The Naturalists: Scientific Travelers in the Golden Age of Natural History and the internationally successful Scurvy: How a Surgeon, a Mariner, and a Gentleman Solved the Greatest Medical Mystery of the Age of Sail. He lives in the Canadian Rockies with his wife and two young children.

1THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SEAFARING WORLD: THE AGE OF SCURVYAN ENGLISH SAILOR RELAXED in an alehouse with companions after a long voyage from the West Indies. After over a year away, he wanted to celebrate his safe return. The merchant ship had returned to Portsmouth with a load of spices and exotic wood. It had been a good run; the winds and weather had been fair and the incidence of disease low. Still, he was lucky to have survived, and several of his fellow mariners had not. He had been ashore for several days, paid out by his captain, and he was enjoying his liberty, spending his hard-earned coin. Downing the last of many mugs of ale, he was surprised to find a shilling at the bottom. Something did not seem right, but he had had much to drink this night. Blessing his good fortune, he pocketed the coin, bade farewell to his drinking companions, and staggered from the crowded interior out onto the dark street, heading for a flophouse. He was followed from the alehouse. Three more men waited for him in the shadows. Armedwith clubs and with stern expressions on their faces, they surrounded him, leaving no room for escape. With dawning horror, the sailor realized his predicament. He felt the coin in his pocket, the King's Shilling, and belatedly knew that it had been placed in his drink, and that the men of the press gang would swear he had gladly taken it and agreed to join a ship's company. The men grabbed him and dragged him, protesting and struggling until a thump on his head silenced him, towards the harbour. A man-of-war had sailed into port and was looking for recruits.The sailor, like countless others, had now joined the Royal Navy. Life was so hard in the navy, the chance of death so high, and the demand for human fuel so insatiable during times of war that sailors in sufficient quantities to navigate the lumbering warships would rarely sign on voluntarily. It was far safer and more rewarding to sail on merchant ships. The navy's need for men was at least double, perhaps triple, the number of able-bodied seamen who willingly served. Ships were chronically short-handed. Offering a bonus to new recruits failed to provide the needed seamen. A quota system, whereby each county was responsible for furnishing to the navy a specified number of sailors, failed. Beseeching men to do their duty for their country also failed. Short of raising wages and improving conditions, the navy could guarantee a ready supply of sailors only by taking them by force.Famous fighting captains who were believed to have good luck, and who could boast of a good chance of prize money from capturing enemy ships, could announce their need for sailors on posters about town and receive a stream of able seamen eager to join the ship's company. But most captains had to resort to the notorious Impress Service. As a consequence, in eighteenth-century Britain men frequently disappeared from seaport towns and villages. Wandering alone one evening, they would be clubbed, dragged aboard a ship in port, and "recruited" into the navy. Wives were often left wondering what had become of their husbands, and children of theirfathers. Many were never seen by their families again. Press gangs patrolled the narrow warrens and alleys of the poor dockside quarters, searching for anyone alone or too drunk to flee, sailors preferably, but during wartime any reasonably able-bodied men would do. Sometimes the new recruits were rounded up by land-based agents of the Impress Service, who were paid a commission to deliver men to whichever ship lay in port. On other occasions, captains were empowered to search for men themselves, employing gangs usually consisting of four stout seamen armed with clubs and--officially, at least--one lieutenant armed with a cutlass, ostensibly used to impress bystanders with his martial appearance and social respectability. They would sally forth from the ship after darkness in pursuit of their quarry.Many of the "recruits" brought in by the press gangs had little or no experience at sea. Although officially the Impress Service had the legal right to deliver only "seamen, seafaring men and persons whose occupations or callings are to work in vessels and boats upon rivers," on short notice nearly anyone would do (providing they weren't influential or wealthy). Once shipboard, the men were subject to the law of the sea, and to leave was desertion. Desertion was punishable by death. The impressed sailor, if he was lucky, could look forward to years of harsh, brutal service at sea. If he was unlucky, he would die without ever setting foot on his native soil again. The naval historian Sir Harold Scott wryly observed that "it was a curious anomaly: the security of citizens depended on the Fleet. The manning of the Fleet was, therefore, a prime necessity, and the citizens--the pressed men among them, at least--were 'made slaves' in order to keep them free." Up to a third of a ship's company could be made up of men pressed from land or taken from incoming merchant ships.The majority of the men newly rounded up by the Impress Service, as might be supposed, were not the pick of the country; they were primarily spindle-legged landlubbers, vagrants, or tramps in the poorest of physical health. The press gang might also roust out the sick, malnourished, or elderly, or receive from local magistrates convicts who were given a choice between severe punishment or the king's service. Seamen aboard incoming merchant ships were also at risk of impressment. The Royal Navy stopped these ships and claimed any men on board, preferably those who had already served in the navy, beyond the absolute minimum needed to sail the vessel. But not all men in the navy were pressed or convicts. Many joined willingly: for a chance to see the world or out of patriotic duty. But some of those inclined to volunteer would do so only at the end of a particularly harsh winter, when a secure place to sleep, regular, if paltry, pay, and the promise of a daily meal overcame their fear of possible death and the inevitable loss of freedom.Once shipboard, duty was paramount. Discipline was strict, authoritarian, and often violent. There was a great social gulf between the commissioned officers and the common crew, and the captain was a virtual dictator while at sea. It was an age of severe punishments; life was cheap, and the concept of workers' rights lay in the distant future. Even minor crimes such as theft would be dealt with harshly, usually by flogging with the dreaded cat-o'-nine-tails. Crimes that seem relatively innocuous, such as disrespect for a superior officer or inattention to duty, were very serious shipboard, where the lives of all depended on each other; these could be punished with a dozen or even a hundred or more lashes--sometimes enough to kill a man. Because there were no standards for punishment, individual captains wielded great power over their crews. Some were known for being brutal martinets, lashing and beating sailors far in excess of their crimes, while others rarely resorted to the lash. Another common but lesser punishment was known as starting; an officer would whack a sailor with his cane if he thought he was moving too slowly or was showing belligerence to authority. Lashing and starting were most prevalent on ships with great numbers of convicts and pressed men, and they created a tense and gloomyatmosphere that was poor for morale and health. The threat of corporal punishment hung over every man's head.Most of the newly pressed recruits in the navy were not mariners and had never been to sea before. Although they all lived and slept together and ate the same food, there was a hierarchy even amongst the common sailors. While a contingent of skilled able seamen performed all the difficult tasks, such as climbing the rigging and setting the sails, the unskilled men, sickly or weak, were good only for hauling on a rope or swabbing the decks. Not only did they have no nautical skill or inclination, but many of the new recruits, and especially those who had recently come from prison, were already afflicted with one of the many illnesses common in the Age of Sail. Even the able seamen on the majority of ships were barely fit for the harsh realities of life at sea, and conditions became worse when the pressed sailors (morose and melancholy at their dreadful fate) and the convicts (delirious from typhus or dysentery) were taken on board and housed with the rest of the crew, thereby spreading discontent and disease throughout the ship's company.Mariners in the eighteenth century suffered from a bewildering array of ailments, diseases, and dietary deficiencies, such that it was next to impossible for surgeons or physicians to accurately separate the symptoms of one from those of another. Niacin deficiency caused lunacy and convulsions, thiamin deficiency caused beriberi, and vitamin-A deficiency caused night blindness. Syphilis, malaria, rickets, smallpox, tuberculosis, yellow fever, venereal diseases, dysentery, and food poisoning were constant companions. Typhus, or typhoid fever, was common on every ship. Spread by infected lice in the frequently shared and rarely cleaned bedding, typhus was so prevalent in the navy that it was known as "ship's fever" or "gaol fever." Man-of-war and merchantman, both were a cozy den for disease.Life shipboard was not conducive to curing or avoiding any of these varied ailments, and indeed was an ideal environment for spreading them. The sailor's wooden world was infested with refuse,trash, rotting flesh, urine, and vomit. The mariners were either crammed into their quarters like sardines in a box or slept, occasionally in good weather, sprawled like hounds on the deck. The holds were crammed with vermin, festering and spoiled provisions, and in some cases rotting corpses. On English and Dutch ships, the primarily Protestant dead sailors were wrapped in their hammocks and pitched overboard--with proper ceremony, naturally. But on the ships from Catholic countries such as France and Spain, the decaying bodies were stowed in the gravel of the hold, mouldering for perhaps months until the ships returned to home port and the dead could be buried in their native soil. The ships always leaked, and pumps could never keep the water our entirely, so the ballast of gravel or sand became incredibly putrid. Ventilation was poor and the bilge gases so noxious that it was extremely hazardous for carpenters to go below to work in the hold. The stench was unbearable, and occasionally men suffocated from inhaling the fumes.Sanitary conditions aboard ships, and particularly the warships of national navies, were as bad as or worse than the filthiest slums then in London, Amsterdam, Paris, or Seville. The cramped, stifling, congested forecastle, where the crew slept, was dark and dingy. The air was clouded with noxious bilge gasses and congested with the sweet, cloying reek of rot and sweat. Sailors slept in dirty bedding and wore the same vermin-infested rags for months on end. The British naval commander Frederick Chamier wrote in The Life of a Sailor of his first days on a ship in port as a young midshipman during the Napoleonic Wars. "Dirty women," he wrote, "the objects of sailors' affections, with beer cans in hand, were everywhere conspicuous: the shrill whistle squeaked, and the noise of the boatswain and his mate rattled like thunder in my ears; the deck was dirty, slippery and wet; the smells abominable; the whole sight disgusting."Overcrowding contributed to the unsanitary conditions and the spread of disease. The largest battleships, weighing approximately 2,500 tons and boasting 120 great guns, yet only several hundred feetlong, could house more than a thousand men. Large crews were needed because, in addition to manning the sails, eight to twelve men were required to operate each gun. Because of the high mortality rates, navy ships were oversupplied with men. The ships themselves were extremely valuable; they took years to build and required two thousand to three thousand mature oak trees each. It was unthinkable to lose a ship of the line because of a lack of manpower to sail it properly. Consequently, a warship requiring a normal complement of a thousand sailors would weigh anchor and depart for sea with many hundreds more crammed aboard. Perhaps five hundred men at any given time slung their hammocks between the great guns, in a compartment no more than 50 feet wide and 150 feet long. Sleeping, coughing, and sneezing with as little as fourteen inches between men encouraged the spread of infectious and contagious diseases. The overcrowding itself was as great a cause of disease as the unsanitary conditions. One of the great and sad ironies of the age was that naval authorities increased the number of men on ships in anticipation of replacing those who died. The overcrowding increased the deaths, however, leading naval authorities to strive for even greater numbers at the start of every voyage. It was a vicious circle that in the 1700s took a terrible toll of human life from all the major seafaring nations, leaving ships dangerously undermanned at sea and occasionally crippling entire fleets.

A warship preparing for sea was a hive of chaotic activity. All hands scuttled about the dock and deck, hauling on rough hemp ropes and hoisting provisions and stores across the crack of water that separated the ship from the provisioning barge. They swabbed the upper deck, scrubbed the gun decks with vinegar, and fumigated the lower compartments with smoking brimstone to cleanse the malignant airs that were believed to be the cause of most ailments.They lowered the wrapped bundles and barrels into the gaping maw of the hatch, stowing everything in the dank bowels of the ship, including carpenters' tools, cutlasses and other weapons for close combat, kegs of gunpowder, mounds of cannonballs, spare spars, dozens of sails, vast coils of rope, tubs of tar, casks of grease, canisters of paint, cords of wood, and buckets of coral.But perhaps most impressive were the mountains of food needed to feed hundreds of mariners for months or years without replenishing. Although ships frequently purchased supplies from local ports, these could not be counted on for price or availability, and particularly in the navy, ships had to be prepared to carry out orders at a moment's notice. Once the provisions had been lowered onto the deck, the barefoot, pigtailed foremast jacks leapt to roll to the central hatch great oak barrels of salted beef, pork, and fish; kegs of English beer and West Indian rum; back-breaking burlap sacks of flour, dried peas, and oats; monstrous wheels of cheese; great blocks of butter; casks of molasses; and a huge quantity of hardtack cakes. The victualling yards of the major European ports were all well supplied to support departing ships on short notice.The standard naval diet varied only slightly over the centuries and only slightly between the various European nations. Ships' provisions were limited by what could be preserved or stored for months at a time without going bad. Salt beef or pork, dried peas or grains, or ship's biscuit were standard fare from the time of the Spanish Armada in the sixteenth century through the period when Dutch merchants piloted their way to Indonesia (the Dutch East Indies) to the era of the great naval battles between France and England in the eighteenth century. The Spanish fed on more oil and pickled vegetables, the Dutch on more sauerkraut and dunderfunk (fried biscuit with lard and molasses), but on the whole the sailors' diet was remarkably constant between nations--it simply reflected the only items that could survive for any length of tim...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherSt. Martin's Griffin

- Publication date2005

- ISBN 10 0312313926

- ISBN 13 9780312313920

- BindingPaperback

- Edition number1

- Number of pages272

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Scurvy: How a Surgeon, a Mariner, and a Gentlemen Solved the Greatest Medical Mystery of the Age of Sail

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. 0.91. Seller Inventory # 0312313926-2-1

Scurvy: How a Surgeon, a Mariner, and a Gentlemen Solved the Greatest Medical Mystery of the Age of Sail

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published 0.91. Seller Inventory # 353-0312313926-new

Scurvy : How A Surgeon, A Mariner, And A Gentlemen Solved The Greatest Medical Mystery Of The Age Of Sail

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 3419450-n

Scurvy: How a Surgeon, a Mariner, and a Gentlemen Solved the Greatest Medical Mystery of the Age of Sail (Paperback or Softback)

Book Description Paperback or Softback. Condition: New. Scurvy: How a Surgeon, a Mariner, and a Gentlemen Solved the Greatest Medical Mystery of the Age of Sail 0.75. Book. Seller Inventory # BBS-9780312313920

Scurvy: How a Surgeon, a Mariner, and a Gentlemen Solved the Greatest Medical Mystery of the Age of Sail

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # ABLIING23Feb2215580106671

Scurvy: How a Surgeon, a Mariner, and a Gentlemen Solved the Greatest Medical Mystery of the Age of Sail

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # I-9780312313920

Scurvy: How a Surgeon, a Mariner, and a Gentlemen Solved the Greatest Medical Mystery of the Age of Sail

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Brand New! This item is printed on demand. Seller Inventory # 0312313926

Scurvy: How a Surgeon, a Mariner, and a Gentlemen Solved the Greatest Medical Mystery of the Age of Sail

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new0312313926

Scurvy: How a Surgeon, a Mariner, and a Gentlemen Solved the Greatest Medical Mystery of the Age of Sail

Book Description Condition: New. . Seller Inventory # 52GZZZ00TX9E_ns

Scurvy (Paperback)

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Paperback. Scurvy took a terrible toll in the Age of Sail, killing more sailors than were lost in all sea battles combined. The threat of the disease kept ships close to home and doomed those vessels that ventured too far from port. The willful ignorance of the royal medical elite, who endorsed ludicrous medical theories based on speculative research while ignoring the life-saving properties of citrus fruit, cost tens of thousands of lives and altered the course of many battles at sea. The cure for scurvy ranks among the greatest of human accomplishments, yet its impact on history has, until now, been largely ignored. From the earliest recorded appearance of the disease in the sixteenth century, to the eighteenth century, where a man had only half a chance of surviving the scourge, to the early nineteenth century, when the British conquered scurvy and successfully blockaded the French and defeated Napoleon, Scurvy is a medical detective story for the ages, the fascinating true story of how James Lind (the surgeon), James Cook (the mariner), and Gilbert Blane (the gentleman) worked separately to eliminate the dreaded affliction. Scurvy is an evocative journey back to the era of wooden ships and sails, when the disease infiltrated every aspect of seafaring life: press gangs recruit mariners on the way home from a late night at the pub; a terrible voyage in search of riches ends with a hobbled fleet and half the crew heaved overboard; Cook majestically travels the South Seas but suffers an unimaginable fate. Brimming with tales of ships, sailors, and baffling bureaucracy, Scurvy is a rare mix of compelling history and classic adventure story. Scurvy took a terrible toll in the Age of Sail, killing more sailors than were lost in all sea battles combined. The threat of the disease kept ships close to home and doomed those vessels that ventured too far from port. The willful ignorance of the royal medical elite, who endorsed ludicrous medical theories based on speculative research while ignoring the life-saving properties of citrus fruit, cost tens of thousands of lives and altered the course of many battles at sea. The cure for scurvy ranks among the greatest of human accomplishments, yet its impact on history has, until now, been largely ignored. From the earliest recorded appearance of the disease in the sixteenth century, to the eighteenth century, where a man had only half a chance of surviving the scourge, to the early nineteenth century, when the British conquered scurvy and successfully blockaded the French and defeated Napoleon, "Scurvy "is a medical detective story for the ages, the fascinating true story of how James Lind (the surgeon), James Cook (the mariner), and Gilbert Blane (the gentleman) worked separately to eliminate the dreaded affliction. "Scurvy "is an evocative journey back to the era of wooden ships and sails, when the disease infiltrated every aspect of seafaring life: press gangs "recruit" mariners on the way home from a late night at the pub; a terrible voyage in search of riches ends with a hobbled fleet and half the crew heaved overboard; Cook majestically travels the South Seas but suffers an unimaginable fate. Brimming with tales of ships, sailors, and baffling bureaucracy, "Scurvy "is a rare mix of compelling history and classic adventure story. Shipping may be from multiple locations in the US or from the UK, depending on stock availability. Seller Inventory # 9780312313920