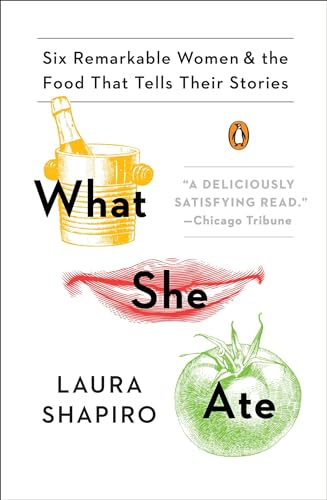

What She Ate: Six Remarkable Women and the Food That Tells Their Stories - Softcover

One of NPR Fresh Air's "Books to Close Out a Chaotic 2017"

NPR's Book Concierge Guide To the Year’s Great Reads

“How lucky for us readers that Shapiro has been listening so perceptively for decades to the language of food.” —Maureen Corrigan, NPR Fresh Air

Six “mouthwatering” (Eater.com) short takes on six famous women through the lens of food and cooking, probing how their attitudes toward food can offer surprising new insights into their lives, and our own.

Everyone eats, and food touches on every aspect of our lives—social and cultural, personal and political. Yet most biographers pay little attention to people’s attitudes toward food, as if the great and notable never bothered to think about what was on the plate in front of them. Once we ask how somebody relates to food, we find a whole world of different and provocative ways to understand her. Food stories can be as intimate and revealing as stories of love, work, or coming-of-age. Each of the six women in this entertaining group portrait was famous in her time, and most are still famous in ours; but until now, nobody has told their lives from the point of view of the kitchen and the table.

What She Ate is a lively and unpredictable array of women; what they have in common with one another (and us) is a powerful relationship with food. They include Dorothy Wordsworth, whose food story transforms our picture of the life she shared with her famous poet brother; Rosa Lewis, the Edwardian-era Cockney caterer who cooked her way up the social ladder; Eleanor Roosevelt, First Lady and rigorous protector of the worst cook in White House history; Eva Braun, Hitler’s mistress, who challenges our warm associations of food, family, and table; Barbara Pym, whose witty books upend a host of stereotypes about postwar British cuisine; and Helen Gurley Brown, the editor of Cosmopolitan, whose commitment to “having it all” meant having almost nothing on the plate except a supersized portion of diet gelatin.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Her first responsibility was one that FDR asked her to take on: he wanted her to manage the domestic side of the White House—a notion that must have reverberated in his mind for the next twelve years like a howl of triumph from Satan himself. Eleanor promptly set out to locate a first- rate housekeeper, someone who would plan and oversee the cooking, cleaning, laundry, and marketing for what was, in effect, a private hotel under public scrutiny. She thought she knew just the right person. Back in 1928, when FDR was running for governor of New York, Eleanor had become involved with the Hyde Park branch of the League of Women Voters and met a local woman who was also active in it: Henrietta Nesbitt, a homemaker with two grown sons and an unemployed husband. She was a strong supporter of FDR’s and went to the same Episcopal church as Eleanor. And her family was hard up. Eleanor saw a way to help. She began hiring Mrs. Nesbitt to bake bread, pies, coffee cakes, and cookies for the constant entertaining that was going on at Hyde Park, and when the Roosevelts moved to Albany Mrs. Nesbitt kept right on baking for them, sending the orders upstate by train. Then FDR ran for president and won. Mrs. Nesbitt was delighted but also a little disappointed. The baking had been “a godsend,” as she wrote in her memoir, White House Diary. Now it was coming to an end, and the Nesbitts, who had been forced to move in with their son and his family, were going to lose their only source of income. But shortly after Thanksgiving, Mrs. Roosevelt stopped by and said she was going to need a housekeeper in the White House. At the time she wrote her memoir, Mrs. Nesbitt was aware that her tenure in the White House was likely to be remembered as a national embarrassment—she had read all the bad press and heard all the complaints—and in her book she made a point of quoting Eleanor’s job offer very precisely: “I don’t want a professional housekeeper. I want someone I know. I want you, Mrs. Nesbitt.”

It’s not clear why Eleanor was so determined to hire an amateur for a job that called for supervising more than two dozen employees, maintaining sixty rooms and their furnishings, preparing meals for a guest list that often doubled or tripled on short notice, feeding sandwiches and sweets to a thousand or more at tea on any given day, and making sure family members and their innumerable overnight guests had everything they might require around the clock. Eleanor’s contacts in Washington, not to mention her friends in home economics, could have given her the names of many candidates far more experienced than Mrs. Nesbitt. But Eleanor was comfortable with this Hyde Park woman, so loyal and accommodating, whose pies and cookies always arrived at the house when they were supposed to, and who very much needed the work. Why look elsewhere?

“Mrs. Nesbitt didn’t know beans about running a White House,” recalled Lillian Rogers Parks, who worked as a maid and seamstress for the Hoovers, the Roosevelts, the Trumans, and the Eisenhowers. Known backstairs as “Fluffy”—because she was so very much the opposite—Mrs. Nesbitt had neither the skills nor the temperament for the immense job she had taken on, and she met the situation by becoming officious, overbearing, and peremptory. The staff loathed her. J. B. West, the longtime White House usher, said the mansion began looking “dingy, almost seedy” under her care, and the kitchen saw plate after plate coming back with gray slices of meat and pallid vegetables barely touched. The president complained steadily about the food, and by 1944 he was saying that the main reason he wanted to win a fourth term was for the pleasure of firing Mrs. Nesbitt. But to the end of Eleanor’s life, she insisted she had made a good hire. “Father never told me he wanted to get rid of Mrs. Nesbitt,” she claimed in a letter to her son James, who had described in a memoir FDR’s vehement feelings about the housekeeper. She added that FDR “often praised” Mrs. Nesbitt’s work—an assertion so blatantly untrue that nobody took it seriously except Mrs. Nesbitt, who made the same claim in her own two books.

Yet Mrs. Nesbitt, the most reviled cook in presidential history, kept a careful record of the lunch and dinner menus she had planned at the White House and gave them to the Library of Congress with the rest of her papers. It’s as if she wanted to announce to all future detractors that contrary to her reputation she had done a splendid job and fully deserved the faith that Eleanor had in her. Hence we have a comprehensive picture of what was served throughout FDR’s administration—not just the state dinners, which every administration publicized, but all the other meals as well. They make it clear, in fact they make it vivid, what everyone was so unhappy about.

Mrs. Nesbitt was under orders to practice strict economy, first because of the Depression and later because of wartime rationing. Beyond this, her only culinary vision was the one she had developed as a small- town home cook who occasionally ate out in modest restaurants. Eleanor looked over the menus every morning, but she was even less adventuresome than Mrs. Nesbitt when it came to feeding people and rarely asked for changes. Apart from this daily conference with the First Lady, Mrs. Nesbitt insisted on absolute control in the kitchen. “Of course, Henrietta did not personally do the cooking, but she stood over the cooks, making sure that each dish was overcooked or undercooked or ruined one way or another,” wrote Lillian Parks. Taste, texture, serving the food at the proper temperature, making sure each dish looked appetizing—these were niceties that did not concern the housekeeper. For dinner she typically offered simple preparations of beef, lamb, chicken, and fish, though by the time they arrived at the table they tended to be cold and dried out. She also deployed an occasional novelty of the sort that appeared in women’s magazines under such names as “Seafood Surprise” and “Ham Hawaiian.” Low- cost main dishes like sweetbreads, brains, and chicken livers appeared frequently, so frequently FDR took to complaining that he was never given anything else. But the greater cause for misery seems to have been lunch, which Mrs. Nesbitt saw as a fine occasion to save money. She built up a small repertoire of dishes based on leftovers and other inexpensive mixtures, and these turned up week after week as regularly as if they were on assignment. Sometimes these mixtures were stuffed into a green pepper, other times into a patty shell, but her favorite way to present them was the most straightforward—on toast. There were curried eggs on toast, mushrooms and oysters on toast, broiled kidneys on toast, braised kidneys on toast, lamb kidneys on toast, chipped beef on toast, and a dish called “Shrimp Wiggle,” consisting of shrimp and canned peas heated in white sauce, on toast.

Another way to stretch just about any sort of food was to turn it into a creamed entrée or side dish, so day after day the Roosevelts and their company encountered creamed codfish, creamed finnan haddie, creamed mushrooms, creamed carrots, creamed clams, creamed beef, and creamed sweetbreads. Egg dishes also appeared with some persistence: she offered stuffed eggs and shirred eggs, and she featured “Eggs Benedictine” until 1938, when somebody finally corrected her. Sometimes the menus make it clear that she was at wits’ end: we see her resorting to a dish she called “Stuffed Egg Salad” for two lunches in a row, and on another presumably frantic day it was sweet potatoes at both lunch and dinner. (She did vary them, adding marshmallows at lunch and pineapple at dinner.)

When it came to the salad course, Mrs. Nesbitt’s interpretation of the possibilities came from a long, uniquely American tradition in which any combination of foods, however unlikely, could be designated a salad simply by serving them on a lettuce leaf. “We leaned on salads of every variety,” she wrote in The Presidential Cookbook, her collection of White House recipes. “Mrs. Roosevelt was especially fond of salads. . . . And even the men, who seemed inclined to frown on vegetables in any form, showed a definite interest in greens when they were fixed in appetizing ways with a tangy dressing.” How the men reacted to “Jellied Bouillon Salad” is not recorded. Other salads that appeared on the White House table, and these must have made quite an impression on foreign visitors unfamiliar with the tradition, included “Stuffed Prune Salad,” “Ashville Salad” (canned tomato soup in a gelatin ring mold), and “Pear Salad,” a hot- weather specialty featuring canned pears covered in cream cheese, mayonnaise, chives, and candied ginger. Mrs. Nesbitt said she sometimes colored the mayonnaise green.

Many of these dishes reflected the American eating habits of her time; others would have been extreme under any circumstances. Not many families began dinner with sticks of fresh pineapple that had been rolled in crushed peppermint candy. But on the whole, Mrs. Nesbitt was setting a familiar if dowdy table, a culinary standard that suited Eleanor very well. She was emphatic about promoting simple, mainstream cuisine as a Roosevelt administration virtue. “I am doing away with all the kickshaws—no hothouse grapes—nothing out of season,” she told The New York Times. “I plan for good and well- cooked food and see that it is properly served, and that must be enough.” And perhaps it would have been, if Mrs. Nesbitt had been able to bring the right instincts or training to her work. She had little of either to draw upon. The arrival of foreign visitors was especially challenging, though she liked to think of herself as rising to the occasion. “For Chinese people I’d always try for a bland menu,” she explained in White House Diary. “Then for the Mexican dinner I’d have something hot, like Spanish sauce with the chicken.” She was especially proud of the nondairy, vegetarian menu she was able to create for the ambassador from Abyssinia and his entourage, who were Coptic Christians, and she carefully kept it on file to reuse when she had to feed Hindus or Muslims. Those who couldn’t eat the clam cocktail or the bluefish presumably filled up on the Mexican corn.

A few of the meals in Mrs. Nesbitt’s collection are marked “Mrs. Hibben’s menu,” a reference to a rare dalliance with gourmandise that took place early in the first administration. After the election, Eleanor received a memo from Ernestine Evans, a former journalist and peripatetic literary agent who took an interest in food and thought it could play a useful role in the new White House. Why not showcase American cooking? Menus could include fine regional dishes—“cornbreads and gumbos and chowders”—authentically prepared with local ingredients. Just as the White House regularly supplied the press with the names of the guests at official dinners, it could also supply the menus; and a commitment to focus on America’s culinary traditions would assure positive news coverage. Evans said she had the right person in mind to help make this happen: Sheila Hibben, author of The National Cookbook and “the best practical cook I know.” Perhaps Hibben could work quietly behind the scenes in the White House kitchen for a few months, developing appropriate menus and recipes. “She should be used like a good architect,” Evans mused. “She should go back and find out what Jefferson served, and be ready always with a great deal of lore, so that every dish has history as well as savor.”

Sheila Hibben was a witty, cosmopolitan food writer who contributed regularly to The New Yorker and other chic magazines. In the introduction to The National Cookbook, she wrote that she had been inspired to start collecting regional American recipes the day she came across a picture in the Sunday paper of a bowl of soup topped with whipped cream—whipped cream, that is, in the shape of a Sealyham terrier. Off she went on a mission to rescue what was still excellent in American cooking, hoping the best recipes would act as a kind of seawall to protect fine regional cookery against crashing waves of the idiotic, the reductionist, and the dreary. A project that began with indignation, she added, ended in patriotism—“a special sort of patriotism, a real enthusiasm for the riches and traditions of America.” Eleanor liked the idea of food that could teach history, and she invited Hibben to visit the White House kitchen and share her ideas and recipes with Mrs. Nesbitt. Alas, there seems to be no record of precisely what happened when Mrs. Nesbitt met this particular challenge to her authority, but in the end, victory went to the housekeeper.

Mrs. Nesbitt’s most important adversary, however, wasn’t in the kitchen; he was in the Oval Office. She and FDR were at odds from the start. “Father, who would have been an epicure if he had been given the opportunity, began grumbling about the meals served under Mrs. Nesbitt’s supervision within a week of her reporting for duty,” wrote his son Elliott in a memoir. “Restricted in his wheelchair from dining out except on ceremonial occasions, he was at the mercy of Mrs. Nesbitt’s kitchen.” FDR liked a decent fried egg in the morning; Mrs. Nesbitt’s were invariably overcooked. He longed for a good cup of coffee; Mrs. Nesbitt’s was bitter. (Finally ...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherPenguin Books

- Publication date2018

- ISBN 10 0143131508

- ISBN 13 9780143131502

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages320

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

What She Ate: Six Remarkable Women and the Food That Tells Their Stories

Book Description paperback. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 0143131508-11-31087884

What She Ate: Six Remarkable Women and the Food That Tells Their Stories

Book Description Condition: New. . Seller Inventory # 52GZZZ009CXR_ns

What She Ate: Six Remarkable Women and the Food That Tells Their Stories

Book Description Condition: New. . Seller Inventory # 5AUZZZ0011ME_ns

What She Ate: Six Remarkable Women and the Food That Tells Their Stories

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # mon0000229021

What She Ate: Six Remarkable Women and the Food That Tells Their Stories

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new0143131508

What She Ate: Six Remarkable Women and the Food That Tells Their Stories

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0143131508

What She Ate: Six Remarkable Women and the Food That Tells Their Stories

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0143131508

What She Ate: Six Remarkable Women and the Food That Tells Their Stories

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0143131508

What She Ate: Six Remarkable Women and the Food That Tells Their Stories

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Brand New. reprint edition. 320 pages. 7.75x5.06x0.78 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # 0143131508

What She Ate: Six Remarkable Women and the Food That Tells Their Stories

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0143131508