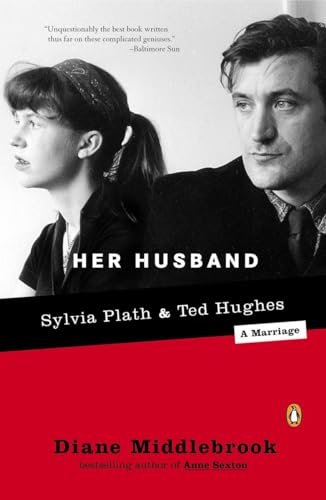

Her Husband: Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath--A Marriage - Softcover

Her Husband is a triumph of the biographer's art and an up-close look at a couple who saw each other as the means to becoming who they wanted to be: writers and mythic representations of a whole generation.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Ted Hughes met Sylvia Plath at a wild party in February 1956 and married her four months later. He was English, twenty-five years old; she was twenty-three, an American. For six years they worked side by side at becoming artists. Then Hughes initiated an affair with another woman, and the marriage collapsed. Hughes moved out and, exactly four months later, Plath committed suicide, leaving behind their two very young children. One of the most mutually productive literary marriages of the twentieth century had lasted only about twenty-three hundred days. But until they uncoupled their lives in October 1962, each witnessed the creation of everything the other wrote, and engaged the other’s work at the level of its artistic purposes, and recognized the ingenu-ity of solutions to artistic problems that they both understood very well. This kind of collaboration is quite uncommon between artists, especially if they are married to each other, and after the publication of Hughes’s prizewinning first book, The Hawk in the Rain, the marriage began attracting the attention of journalists. In January 1961, Hughes and Plath were interviewed for a radio broadcast on the BBC, Two of a Kind, that displays them at the apex of their compatibility. The interviewer, Owen Leeming, asked whether theirs was “a marriage of opposites.” As if in a movie by Woody Allen, Hughes said they were “very different” at the same moment Plath said they were “quite similar.” Explaining “different,” Hughes allowed that he and Plath had similar dispositions, and worked at the same pace—indeed, so deep were the similarities that he often felt he was drawing on “a single shared mind” that each accessed by telepathy. But he and Plath drew on this shared mind for quite different purposes, he said, and each of their imaginations led a thoroughly “secret life.”

Explaining “similar,” Plath said that though she and Hughes had very different backgrounds, she kept discovering unexpected likenesses. Hughes’s fascination with animals, for example, had opened up for her the subject of beekeeping, which was one of her father’s scholarly pursuits. More of her own history had become available to her poetry because Hughes was so interested in it, she said: that was how the similarities were developing in their work—though the work itself was not at all similar, she insisted. Did she too believe they had a single shared mind? No, Plath laughed. “Actually, I think I’m a little more practical.”

Just such a dance through the minefield of their differences characterized their partnership at its best. It succeeded because each of them invested wholeheartedly in whatever the other was working on, even when the outcome was of dubious merit. In the late 1950s, Hughes helped Plath develop plots for stories she could publish in women’s magazines, even though he regarded fiction-writing as a false direction for Plath. At the time, he saw, accurately, that only conventional plots in which people got born, married, or killed released her distinctive “demons,” so he encouraged her to invest in whatever mode was most productive of tapping these unique sources of energy. Plath, for her part, loyally defended the incoherent and unmarketable plays in which Hughes promoted the esoteric ideas he was hooked on, beginning in the early 1960s—she was as interested in his artistic strategies as she was in the results. Paradoxically, their intimate creative relationship enabled each of them to conduct better the “secret life” expressed in their art. The rupture in their marriage closed down this literary atelier. But poetry had brought Hughes and Plath together, and poetry kept them together until Hughes’s death in 1998. Hughes inherited Plath’s unpublished manuscripts, appointed himself her editor and made her famous. In 1965, when he brought out the volume titled Ariel, which contained Plath’s last work, he said proudly, “This is just like her—but permanent.” By that year, the world was ready to agree with him about Plath’s importance. Poets rarely become cultural icons, but Plath’s suicide had occurred just when women’s writing was beginning to stimulate the postwar women’s movement. The posthumous publication of Plath’s poetry, fiction, letters and journals added her voice to a swelling chorus of resistance to the traditional positions women occupied in social life. The more celebrated Sylvia Plath became, the more people wanted to know what role her marriage to Ted Hughes had played in the catastrophe of her decision to die—especially after it became widely known that the woman Hughes left her for, Assia Wevill, had also committed suicide and had killed the daughter she had borne to Hughes.

Hughes spent the rest of his life quashing public discussion of these painful episodes in his private life. But shortly before his death in 1998, he released two books of poems that explore the subject of what it meant to have been the husband of Sylvia Plath. One was titled Birthday Letters. Speaking to Plath as if she were looking back with him from the vantage of their middle age, Hughes reflected on the array of circumstances that drove them together in 1956, and kept them together for six years; and he also proposed an explanation of the psychological issues behind her suicide.

Birthday Letters became a huge commercial success, but most people never even heard about the other book, Howls and Whispers, which was published in an expensive limited edition, and was never reviewed in the press. To make Howls and Whispers Hughes had reserved eleven poems from the manuscripts that became Birthday Letters, as a winemaker sets aside the choicest vintage for special labeling. In its keynote poem, “The Offers,” the ghost of Sylvia Plath appears to Ted Hughes three times. On each visit she tests him; on the last visit she warns, “This time don’t fail me.”

That startling phrase sends a pulse of light back through every page Hughes had published since Plath’s death. It points our attention to the theme in Hughes’s work of how marriages fail, or how men fail in marriage. Sometimes his work contains a representation of himself as the character who fails, as in Birthday Letters. In other writings, such as the translations of the grand works of Western literature with which Hughes occupied himself toward the end of his life—Racine’s Phèdre, Tales from Ovid, the Alcestis of Euripides—Hughes brings empathy to the theme of marriage under duress. His versions of these were all produced for the stage, and audiences were quick to intuit that a second passionate story—Hughes’s own story—was being explored, inexactly, within the dynamics of a venerable classic.

Though only 110 copies of Howls and Whispers were printed, Hughes acquired a large audience for its most important poem, “The Offers,” by releasing it in the London Sunday Times on October 18, 1998. Ten days later, Hughes died. Whether by accident or design, that sentence spoken by Sylvia Plath through the medium of Ted Hughes would be on record as his last words. Birthday Letters offers us a way to see Ted Hughes from inside his partnership with Plath; “The Offers” requires that we see them as inseparable, even in death. “This time, don’t fail me” is the voice of poetry itself, which Plath embodied; the persona created in his work is her husband; and that persona is his contribution to the history of poetry.

Hughes began developing this autobiographical persona, her husband, when he was nearly fifty years old. After years of attempting to avoid autobiographical writing, Hughes had come to believe that the voice in poetry had to issue from a human being situated in historical time and place, engaged in attempting to “cure” a wounding blow to his psyche inflicted by an historically significant conflict. The struggle conducted in a poet’s art was his way of participating in history. Hughes also saw that no single work of writing stood alone, that a strong writer’s work proceeded by accretion over time. Hughes observed that the poetic DNA expressed itself in single, definitive images or a “knot of obsessions” produced early in the poet’s career and repeated in variations thereafter. Like the cells of a developing foetus, each work contained the DNA of the whole man, that is, the whole image of the persona.

“The Offers” is the central poem in Hughes’s work of self-mythologizing. It marks the turning point in his creative life, showing in a set of images how the poet’s powers were summoned back to him following the two successive personal disasters of the suicides of women close to him. What would it mean not to fail the claims that Woman had made on his psyche from childhood on? How could he negotiate the urgency of contradictory needs for separation from her, and for dialogue with her? During the last two decades of his career, these questions informed works of lasting importance by Ted Hughes. These included Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being, in which he investigated the conflicted “way of loving” to be found in Shakespeare’s writing; and the autobiographical poems wherein Hughes provided himself with a mythical childhood, much in the manner of Wordsworth, setting forth an account of the growth of the poet’s mind. But in Hughes’s account, marriage was the culmination of that developmental path. And marriage forced a man into the underground of his own darkness. In “The Offers,” he is stepping naked back into the world, no longer in the form of a man, but as a persona.

This is the myth that can be pieced together from its scattered manifestations in Hughes’s published works and private papers; and Hughes made sure that it could be found. The year before his death, he sold a very large collection of his manuscripts and letters to Emory University in Atlanta. And during the latter years of his career, anxious about his relationship to posterity, he responded generously to inquiries from scholars and critics interested in his work, and granted interviews about his beliefs and practices, and about his personal life.

In just such ways did Ted Hughes insure that his persona as a poet would survive him and would slowly work its way into the consciousness of posterity. He said as much to Sylvia Plath’s mother, Aurelia, back in 1975 while they were editing some of Plath’s correspondence for publication. Hughes requested that many references to himself be excised from this book. Aurelia Plath protested that Hughes was asking her to leave out too many informative details. He responded in a long letter, of which he made a carbon copy that he placed in his own archive. “An impartial scholar will eventually—no doubt—put all these notes in quite pitilessly,” he assured her. “In time everything will be quite clear, whatever has been hidden will lie in the open.”

Hughes was speaking, specifically, about his relationship to Sylvia Plath. He understood that after his death the story of their marriage would belong to the cultural history of the twentieth century. As he knew, the totality of his work contained a unique and poignant account of how they struggled together to become writers: what each gave, what each took; how their marriage floundered and their art did not. Her Husband threads together the story Hughes told and the history that surrounds the story. Drawing from his books and papers, it follows a single line of inquiry through the maze of Hughes’s life as he enters into the partnership, struggles and prospers in it, loses the partner but not the relationship, and turns the marriage into a resonant myth.

chapter one

Meeting

(1956)

Ted Hughes believed that destiny had singled him out to become the husband of Sylvia Plath. “The solar system married us,” he claimed, when he re-created their meeting in Birthday Letters, locating the astrological coordinates very precisely. The date was Saturday, February 25, 1956, under the sign of Pisces, in the zodiac; the place was Cambridge University, from which Hughes had graduated a year and a half earlier. During the week he was living in a borrowed flat in London, working at a glamorous-sounding day job as a reader of fiction submissions at the film company J. Arthur Rank. But he continued to spend his weekends in Cambridge, hanging out with friends, mainly poets who were still enrolled at the university. They were ambitious, idealistic, apprentice artists, and that winter Hughes joined them in putting together a very small, very literary magazine, St. Botolph’s Review. One of the contributors, an American named Lucas Myers, lived in a repurposed chicken coop behind the rectory of St. Botolph’s Church, off campus. His residence inspired the cheeky title—these poets were ultra-anti-establishment. Friends began peddling copies of St. Botolph’s Review around the Cambridge colleges on publication day, spreading word that a launch party would be held at rooms in Falcon Yard that night. Sylvia Plath bought a copy from an American cousin of one of the poets, and he invited her to the launch.

Plath accepted immediately; here was an opportunity she had been waiting for. She was studying literature at Cambridge on a two-year Fulbright Fellowship after graduating from Smith, a prestigious women’s college in New England. Her writing had won minor literary prizes in the United States and was beginning to appear in such American magazines as Harper’s, Mademoiselle, The Nation, and Atlantic Monthly. Arriving at Cambridge, she had quickly learned that the literary world was tightly networked in Britain; even the limpest student publications were scouted for new talent by London publishers, who were often themselves Cambridge graduates. She immediately began submitting work to college publications. In January, two of her poems had been printed in a little magazine called Chequer—and not only published but, to her amazement, scoffed at, in a fierce little low-budget paper called Broadsheet, which was produced every two weeks on a mimeograph machine by some of the St. Botolph poets. The men who reviewed Plath’s poems disliked on principle the formal verse at which she was very skillful, and on principle they derided what they disliked. “Quaint and eclectic artfulness,” the reviewer labeled Plath’s style, then added, “My better half tells me ‘Fraud, fraud,’ but I will not say so; who am I to know how beautiful she may be.”

The stapled pages of Broadsheet were read avidly by the local poets, and Plath was mortified at being so manhandled. This had been her first exposure to the blokishness of English literary culture. What bothered her most, though, was that little refrain “fraud, fraud.” Plath was aware of her shortcomings and didn’t like them to be noticed by others. Yet the critic’s rhetoric gave her an opening. Did he want to see whether she was beautiful? She would introduce herself. She put on a pair of red party shoes and smoothed back her pageboy with a red hair band, then went to a bar with her date for the evening, where she fortified herself with several whiskeys. But before getting high she had fortified herself another way: she had memorized some of the poems in St. Botolph’s Review.

The party was well under way by the time Plath arrived in Falcon Yard and climbed in her red shoes up the stairs to the Women’s Union, where a jazzy combo hammered music into the babble of raised voices. Plath started working the r...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherPenguin Publishing Group

- Publication date2004

- ISBN 10 0142004871

- ISBN 13 9780142004876

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages384

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Her Husband: Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath--A Marriage by Middlebrook, Diane [Paperback ]

Book Description Soft Cover. Condition: new. Seller Inventory # 9780142004876

Her Husband: Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath--A Marriage

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Brand New! This item is printed on demand. Seller Inventory # 0142004871

Her Husband

Book Description Condition: New. pp. 384. Seller Inventory # 26660167

Her Husband: Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath--A Marriage (Paperback or Softback)

Book Description Paperback or Softback. Condition: New. Her Husband: Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath--A Marriage 0.78. Book. Seller Inventory # BBS-9780142004876

Her Husband: Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath--A Marriage

Book Description Condition: New. Buy with confidence! Book is in new, never-used condition. Seller Inventory # bk0142004871xvz189zvxnew

Her Husband: Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath--A Marriage

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Seller Inventory # 353-0142004871-new

Her Husband: Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath--A Marriage

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # I-9780142004876

Her Husband

Book Description Condition: New. pp. 384. Seller Inventory # 8236312

Her Husband: Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath--A Marriage

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # DADAX0142004871

Her Husband : Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath--A Marriage

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 2507494-n