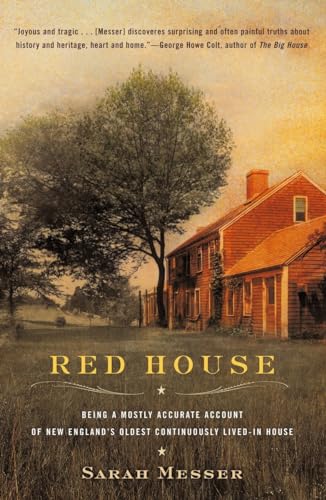

Red House: Being a Mostly Accurate Account of New England's Oldest Continuously Lived-in House - Softcover

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Before the highway, the oil slick, the outflow pipe; before the blizzard, the sea monster, the Girl Scout camp; before the nudist colony and flower farm; before the tidal wave broke the river's mouth, salting the cedar forest; before the ironworks, tack factory, and shoe-peg mill; before the landing where skinny-dipping white boys jumped through berry bushes; before hayfield, ferry, oyster bed; before Daniel Webster's horses stood buried in their graves; before militiamen's talk of separating; before Unitarians and Quakers, the shipyards and mills, the nineteen barns burned in the Indian raid—even then the Hatches had already built the Red House.

The surname Hatch most commonly means a half-door, or gate, an entrance to a village or manor house. It describes a person who stands by the gate; a person newly born; a person who waits.

My father could not wait. He had made an appointment with a real-estate agent, but when he found himself on a house call in Marshfield, Massachusetts, he decided to see the Red House himself. It was August 1965, and he was a thirty-three-year-old Harvard Medical School graduate with a crew cut and bow tie, married to my mother for just four months. Done with his residency and his army service, he had begun to specialize in radiology— broken bones, mammograms, GI series. The practice of seeing through people. With all the self-consciousness of a latter-day Gatsby, he would eventually raise a herd of kids patchworked together as “New Englanders”—four from his first marriage, four with my mother. But for now he was moonlighting for extra cash and driving his sky-blue VW Beetle down dirt roads, into brambles and dead-ends.

Marshfield, then as now, is a coastal community thirty miles south of Boston, 225 miles north of New York City, whose famous residents over the years have included “The Great Compromiser” Daniel Webster, some Kennedy offspring, and Steve Tyler of Aerosmith. Driving through the north part of town, my father passed seventeenth- and eighteenth-century houses, two ponds where mills had been. The afternoon light lay drowsy, the air motoring with insects. He knew he was getting close to something, and his stomach clenched. He had always loved ancient rooflines and stone walls, half- collapsed barns—templates of what had come before—plain churches, fields rolling down to rivers, shipyards. Yet, within this two-mile stretch, modern houses and gas stations had grown up around their remains like flesh over bone. He was following his intuition, as if, eyes closed in a dream, he felt his way with his hands stretched out. The road began a violent S-curve at the edge of a string of ponds. At the blind part of the curve, my father found the road to the house, and turned there to begin the half-mile drive past yet another pond.

He drove by the dilapidated Hatch Mill, over the narrow bridge, then through a canopy of crab-apple trees, over a stream that ran beneath the road. It was the last few weeks of summer, and the timothy was high at the roadside, the milkweed setting off parachute seeds.

Meanwhile, in the adjacent town of Norwell, in the apartment he was renting, my mother was preparing his four children for a bath. They were: Kim, seven; Kerry, five; Kate, four; and Patrick, three. The children were spending the summer away from their mother in California. They had been to Martha's Vineyard, Benson's Wild Animal Farm; they had spent the day riding bicycles on the blacktop driveway.

Lately a raccoon had been banging the lids of the garbage cans below the second-floor bathroom window each night. “That raccoon with his black mask, that thief,” they'd say. My mother was relieved: animal stories were common ground. She said, “It's getting dark; do you think the raccoon is out there?” She squeezed Johnson's baby shampoo into one hand, and then turned the water off. The children shrieked, “Raccoon! Raccoon!” Pale-skinned kids with tan lines: Kim, tall, broad-cheekboned; Kerry and Patrick, a girl- and-boy matched pair with the same androgynous haircut; Kate, a tantrum-throwing tow- head.

My mother, twenty-seven years old and petite, wore her hair long, usually in braids or in a large bun with a thin path of gray twisting through it like a skunk stripe. That day she wore it in a ratty ponytail, having had no time to brush it. Her only cosmetics: an occasional eyebrow-penciling, and lipstick in the evening if she was going out. It had been almost four years since my mother, a lab technician, had met my father at the cafeteria in Children's Hospital in Boston. As she stood in line, she saw him leave his dirty plate and tray, linger, exit the cafeteria, and then return to the line. He was wearing his signature bow tie. He approached her and asked her to have lunch with him.

“You already ate,” she said.

“I'll eat again,” he replied.

From the beginning, my father had mentioned his divorce and his custody of the children for school vacations and three months every summer. Early in the relationship, my father had brought my mother and the children to Cape Cod, where she had her own room in the rented cabin. Nearly every night, Kim had sanded and short-sheeted the bed, leaving seaweed and crabs under the blankets. Besides these incidents, though, the children gave her little indication that she was unwanted. Summer was over, and the next day they were returning to California. The bathtub was by the window, and when they stood at the edge, the children could look down on the dented lids of the three garbage cans. My father had said that the house call would take only an hour at most. Now it was getting late, and my mother had no idea where he was.

He rounded the corner at a large white house, turning sharply to the right at a vine- covered lamppost. He drove through two large stones that made a gate. Then, suddenly, the house was before him, rambling to his left along the crest of a ridge. Below, to his right, a yard fell away into a field of ragweed, bullfrogs.

In architectural terms, the house my father saw would be described as a five-bay, double- pile, center-chimney colonial. It had post-and-beam vertical-board construction, a granite foundation, and small-paned windows. The windows were trimmed with chipped white paint, the body of the house was a deep red—Delicious Apple Red, Long Stem Rose Red, Evening Lip-Stick Red, Miss Scarlett Red, a red that neared maroon. Otherwise, the house was plain and, with its the chimney in the middle of the roof against a backdrop of sky, appeared as simple as a child's drawing of a house: big square and triangle, smaller square on top. The cornice seemed the only detail out of place: attached to the doorway as if to elevate the exterior from utilitarian farmhouse to Victorian estate, it hinted at Greek or Roman Revival, something lofty—like a hood ornament on a Dodge Dart.

The house was large and debauched. Four bushes grown shaggy with tendrils sat beneath the first-floor windows. Lilac trees tangled the farthest ell. The driveway wound around the house to the right, where it climbed a small hill. In the backyard, a man and woman sat in lawn chairs drinking old-fashioneds. It was 5 p.m.

My father, stepping out of the rusted VW, might have appeared to Richard Warren Hatch and his wife, Ruth, to be an affable character—friendly and perhaps a bit too unassuming, with a boyish way of loping when he walked. My father was raised in Polo, Illinois, a small farming town known only for its proximity to Dixon, the birthplace of Ronald Reagan. He was six foot two, with dark hair and bright-blue eyes, size-thirteen feet, crooked teeth, prominent ears, and a nose that had been broken seven times playing football. He was the son of a cattle-feed salesman and a grocery-store clerk. In 1948, he was the captain of his high school's undefeated and untied state-champion football team—a 188-pound fullback once described as a “ripping, slashing ball carrier capable of chewing an opponent's line to shreds.” He was from a one-street, one-chicken-fried- steak-restaurant, one-road-leading-out-into-cornfields, one-stand-of-trees, one-historical- marker-from-the-Indian-war, one-railroad-track town. A town with a history of drive-by prairie schooners. More than anything, he had wanted to get out, and probably even now, sixteen years later, he still wore that desire in the face he presented to the unknown, to strangers. Few of my father's ancestors had ever owned anything; his parents still rented the house they'd lived in for twenty years. Harvard had taught him to love tradition and antiquity, and my father was impatient for a life he had only caught glimpses of in the educated accents of professors and the boiled-wool sweaters of his college roommates' parents. He was looking for a piece of history different from the one his own heritage had provided him. He was looking for just this type of New England home.

The older couple did not get up to greet my father when he closed the car door. But they did smile. So he walked up the yard toward the house and their arrangement of chairs. “I've got an appointment to see the house on Monday,” he said. It was now Saturday. “Oh yes,” Richard Warren Hatch said, “we've heard about you.”

R

Inside, the house was low-ceilinged and dark. Hatch led my father through the honeycomb of rooms, past walls with buckled plaster and wide-paneled boards. Doors slanted in their frames, wind blew out the mouths of small fireplaces. Candleholders extended from mantels like robot arms. Rooms opened into more rooms of boxed and hand-hewn beams. A staircase on the north side of the house unfolded itself like a tight, narrow fan, disappearing to the second floor. The house smelled old, the product of its accumulated history—books and talcum powder, wood, silver polish.

Hatch showed my father old photos in which the paint peeled off the house in ribbons, the sides clapboarded and bowed, the trim gone gray. Hatch had hardly led my father through the inside of the house and already he was revealing its history—the way a parent might present to guests his child's baby pictures, framed drawings, and graduation photos arranged along a hallway before introducing the actual child. The photos depicted several driveways ringed with post, fences long gone, absent gates—the house standing starkly in a nude landscape. They showed a house often in disrepair: sagging roofline, loose shingles. In one photo, a barn loomed larger than the house, extending at a right angle toward the pond. The house and the barn together formed an elongated ell. Windows stacked three stories up the barn's flat red side. The roofs glowed grayish in the photo, and in the foreground, hoed rows of a garden extended toward the bottom of the frame. One photo, circa 1900, showed three small children standing in front of the house in long white shifts that glowed like filament against the dark clapboards.

What the photos did not show, of course, was the beginning—the narrowness of the first structure, the forest behind it, the river a distant smudge, the piles of stumps and roots torn out of the ground, the parts that could not be used for shipbuilding knees burned in bonfires. The photos did not show the stones dug out of the earth for cellars and walls. How the house exterior was first covered with boards, or the roof thatched with reeds, or the windows crosshatched. The photos did not show the close-string stairway replacing a ladder, or someone stand-ing too far in the kitchen's giant hearth when the pot spilled and a skirt hem caught flame, burning lard pouring out over the floor. The photos caught occasional in-between moments, but they implied more, and my father, prodded by Hatch, began to imagine the lives of ancestors—Puritans, shipbuilders, somber Victorians—the blurred wheels of a chaise along the lane in a time before telephone poles.

Hatch led my father, finally, to the root cellar beneath the house. They walked through the tin-backed door from the boiler room into what Hatch called “the passageway.” It was more of a tunnel, really, twenty feet long and curving slightly—the stone walls supported by cement and brick. When he extended his arms to the side, my father could touch both walls in the passageway, the stones damp, sweating. My father was fidgeting, talking too much.

“My parents lived in Chicago,” he said. “They never finished high school.”

The passageway opened into a large underground room where stood part of a chimney, the carved-out kettle drum of the original cellar behind a stairway of half-log beams that led up to a trapdoor in the ceiling, which was the floor of a closet in a room above them. It was the most primitive part of the house. The room smelled of something sweet and dank. Several potatoes grew eyes in the corner. Wires stapled to the underside of boards of the floor above snarled with webs, the mummified bodies of spiders.

“My father played poker with John Dillinger,” my father said. “During the Depression, he had a general store that went under.”

“These are very old beams,” Hatch said, pointing up. “They're part of the original cellar and structure of the old part of the house.”

My father stopped, looked up at the beams.

“My mother, you know, she has a heart condition—rheumatoid, arrhythmia.”

Hatch nodded, seemed distracted. He was built like a ladder. A bunch of wiry hair grew out of his eyebrows. Whenever he talked, his voice boomed off stone, as if the volume were turned up too loud in the room. My father found himself nodding; the tone of Hatch's voice was one of antiquarian authority.

My father, a storyteller, thought of narratives he could recycle in the appropriate occasion. “One time . . .” Or “I once knew this crazy guy . . .” But he had learned Hatch was a writer; had been the head of the English department at Deerfield Academy from 1925 to 1941; had served aboard the battleship New Mexico and the aircraft carrier Yorktown in World War II; had been married with kids and divorced; had since 1951 lectured at the Center for International Studies at MIT, researching and writing about U.S. foreign policy. He had more stories to tell than my father.

Earlier, Hatch had told my father that his great-great-great-great-great-grandfather Walter Hatch had built the house in 1647; that it had always been called the “Red House”; that it was one of the first houses built in this area called Two Mile, which was also casually referred to as “Hatchville” thanks to prolific and intermarrying progeny. As a testament to this, Walter Hatch's framed will, dated 1681 and written in legal English, hung on the living-room wall as it always had, stating that the house should be passed on to “heirs begotten of my body forever from generation to generation to the world's end never to be sold or mortgaged from my children and grandchildren forever.” While talking to my father, Hatch had traced the lines of the will with his finger. My father was having difficulty absorbing everything. He gazed at the will, the paper the color of a grocery bag trapped under the glass now streaked with Hatch's fingermarks.

“This house has been in my family for eight generations,” Hatch repeated, delivering his most subtle sales pitch. “The Oldest Continuously Lived-In House in New England,” he said.

On the cement floor be...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherPenguin Books

- Publication date2005

- ISBN 10 0142001058

- ISBN 13 9780142001059

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages400

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Red House: Being a Mostly Accurate Account of New England's Oldest Continuously Lived-in House

Book Description Condition: New. Buy with confidence! Book is in new, never-used condition. Seller Inventory # bk0142001058xvz189zvxnew

Red House: Being a Mostly Accurate Account of New England's Oldest Continuously Lived-in House

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Seller Inventory # 353-0142001058-new

Red House: Being a Mostly Accurate Account of New England's Oldest Continuously Lived-in House

Book Description paperback. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 0142001058-11-31841759

Red House: Being a Mostly Accurate Account of New England's Oldest Continuously Lived-in House

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Reprint. Seller Inventory # DADAX0142001058

Red House: Being a Mostly Accurate Account of New England's Oldest Continuously Lived-in Ho use (Paperback or Softback)

Book Description Paperback or Softback. Condition: New. Red House: Being a Mostly Accurate Account of New England's Oldest Continuously Lived-in Ho use 0.59. Book. Seller Inventory # BBS-9780142001059

Red House: Being a Mostly Accurate Account of New England's Oldest Continuously Lived-in House

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0142001058

Red House : being

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 3249487-n

Red House: Being a Mostly Accurate Account of New England's Oldest Continuously Lived-in House

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # I-9780142001059

Red House (Paperback)

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Paperback. In her critically acclaimed, ingenious memoir, Sarah Messer explores Americas fascination with history, family, and Great Houses. Her Massachusetts childhood home had sheltered the Hatch family for 325 years when her parents bought it in 1965. The will of the houses original owner, Walter Hatchwhich stipulated Red House was to be passed down, "never to be sold or mortgaged from my children and grandchildren forever"still hung in the living room. In Red House, Messer explores the strange and enriching consequences of growing up with another familys birthright. Answering the riddle of when shelter becomes first a home and then an identity, Messer has created a classic exploration of heritage, community, and the role architecture plays in our national identity. With a poet's eye for clever detail and an ear for the rhythm of place and language, Messer's work of living history tells the story of an American family--whose ancestral home was purchased by her parents--dating back to its wild beginnings in colonial New England. Photos & illustrations. Shipping may be from multiple locations in the US or from the UK, depending on stock availability. Seller Inventory # 9780142001059

Red House: Being a Mostly Accurate Account of New England's Oldest Continuously Lived-in House

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0142001058