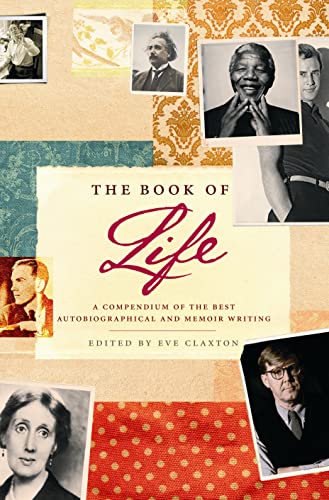

The Book of Life - Hardcover

An engrossing anthology of extracts from some of the finest memoirs ever written, including those of: Charlie Chaplin, Alan Bennett, Muhammed Ali, Ghandhi, Primo Levi, Katherine Hepburn, Nabokov, Darwin and Nelson Mandela.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

Eve Claxton is a writer and journalist for a variety of English and American publications including Vogue, Tatler and the Daily Mail. After gaining a First in English and American Literature at Manchester University, she lived in Hong Kong and New York. This is her third book, her most recent being a guidebook to the best bookshops of New York.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

BEGINNINGS

AGES 0-12

'My autobiography, however, is without any

artifice; nor is it intended to instruct anyone;

but, being merely a story, recounts my life,

not tumultuous events. Like the lives of Sulla,

of Caius Caesar, and even of Augustus, who,

there is no doubt, wrote accounts of their

careers and deeds, urged by the examples

of the ancients, so, in a manner by no means

new or originating with myself, do I set

forth my account.'

GIROLAMO CARDANO,

THE BOOK OF MY LIFE, 1576

ST AUGUSTINE

For at that time I knew how to suck, to be satisfied when comfortable, and to cry when in pain - nothing beyond.

Afterwards I began to laugh - at first in sleep, then in waking. For this I have heard mentioned of myself, and I believe it (though I cannot remember it), for we see the same in other infants. And now little by little I realised where I was, and wished to tell my wishes to those who might satisfy them, but I could not! For my wants were within me, while they were without, and could not by any faculty of theirs enter into my soul. So I cast about limbs and voice, making the few and feeble signs I could, like, though indeed not much like, unto what I wished; and when I was not satisfied - either not being understood or because it would have been injurious to me - I grew indignant that my elders were not subject unto me, and that those on whom I had no claim did not wait on me, and avenged myself on them by tears. That infants are such I have been able to learn by watching them; and they, though unknowing, have better shown me that I was such a one than my nurses who knew it.

And, behold, my infancy died long ago, and I live.

THE CONFESSIONS OF ST AUGUSTINE, 397-400

ARIEL DORFMAN

I was a baby; a pad upon which any stranger could scrawl a signature. A passive little bastard, shipwrecked, no ticket back, not even sure that a smile, a scream, my only weapons, could help me to the surface. And then Spanish slid to the rescue, in my mother's first cry, and soon in her murmurs and lullabies and in my father's deep voice of protection and in his jokes and in the hum of love that would soon envelop me from an extended family. Maybe that was my first exile: I had not asked to be born, had not chosen anything, not my face, not the face of my parents, not this extreme sensitivity that has always boiled out of me, not the early rash on my skin, not my remote asthma, not my nearby country, not my unpronounceable name. But Spanish was there at the beginning of my body or perhaps where my body ended and the world began, coaxing that body into life as only a lover can, convincing me slowly, sound by sound, that life was worth living, that together we could tame the fiends of the outer bounds and bend them to our will. That everything can be named and therefore, in theory, at least in desire, the world belongs to us. That if we cannot own the world, nobody can stop us from imagining everything in it, everything it can be, everything it ever was.

HEADING SOUTH, LOOKING NORTH: A BILINGUAL JOURNEY, 1998

HARRIET MARTINEAU

My first recollections are of some infantile impressions which were in abeyance for a long course of years, and then revived in an inexplicable way, as by a flash of lightning over a far horizon in the night. There is no doubt of the genuineness of the remembrance, as the facts could not have been told me by anyone else. I remember standing on the threshold of a cottage, holding fast by the doorpost, and putting my foot down, in repeated attempts to reach the ground. Having accomplished the step, I toddled (I remember the uncertain feeling) to a tree before the door, and tried to clasp and get around it; but the rough bark hurt my hands.

HARRIET MARTINEAU'S AUTOBIOGRAPHY, 1877

HANNAH LYNCH

The picture is clear before me of the day I first walked. My mother, a handsome, cold-eyed woman, who did not love me, had driven out from town to nurse's cottage. I shut my eyes, and I am back in the little parlour with its spindle chairs, an old-fashioned piano with green silk front, its pink-flowered wallpaper and the two wonderful black-and-white dogs on the mantelpiece ...

I do not remember my mother's coming or going. Memory begins to work from the moment nurse put me on a pair of unsteady legs. There were chairs placed for me to clutch, and I was coaxingly bidden to toddle along, 'over to mamma'. It was very exciting. First one chair had to be reached, then another fallen over, till a third tumbled me at my mother's feet. I burst into a passion of tears, not because of the fall, but from terror at finding myself so near my mother. Nurse gathered me into her arms and began to coo over me, and here the picture fades from my mind.

AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF A CHILD, 1899

THOMAS CARLYLE

My earliest [memory] of all is a mad passion of rage at my elder Brother John (on a visit to us likely from his grandfather's); in which my father too figures though dimly, as a kind of cheerful comforter and soother. I had broken my little brown stool, by madly throwing it at my brother; and felt for perhaps the first time, the united pangs of Loss and of Remorse. I was perhaps hardly more than two years old; but can get no one to fix the date for me, though all is still quite legible for myself, with many of its [features] ... Backwards beyond all, are dim ruddy images, of deeper and deeper brown shade into the dark beginnings of being.

REMINISCENES, 1881

HENRY JAMES

Partly doubtless as the effect of a life, now getting to be a tolerably long one, spent in the older world, I see the world of our childhood as very young indeed, young with its own juvenility as well as with ours; as if it wore the few and light garments and had gathered in but the scant properties and breakable toys of the tenderest age, or were at the most a very unformed young person, even a boisterous hobbledehoy. It exhaled at any rate a simple freshness, and I catch its pure breath, at our infantile Albany, as the very air of long summer afternoons - occasions tasting of ample leisure, still bookless, yet beginning to be bedless, or cribless; tasting of accessible garden peaches in a liberal backward territory that was still almost part of a country town, tasting of many-sized uncles, aunts, cousins, of strange legendary domestics, inveterately but archaically Irish, and whose familiar remarks and 'criticism of life' were handed down, as well as of dim family ramifications and local allusions Ñ mystifications always - that flowered into anecdote as into small hard plums, tasting above all of a big much-shaded savoury house in which a softly-sighing widowed grandmother, Catherine Barber by birth, whose attitude was a resigned consciousness of complications and accretions, dispensed an hospitality seemingly as joyless as it was certainly boundless.

A SMALL BOY AND OTHERS, 1913

SHERWIN B. NULAND

My father does not actually appear in my earliest memory of him. But the threat of his furious anger looms over the series of moments even as they are recalled.

It is in the form of single still images that I remember him from those early years. Each picture is preserved as though a camera had caught a series of lifetime's memories in individual blinks of an eye. Sometimes, an image is followed by a brief cinematic flow of film, but rarely more. And always a distinct emotion or mood is brought back to my mind when the pictures appear.

It is mid-afternoon and I have just spied Daddy's pocket watch and chain on a small table alongside the living-room couch. The sight of the inexpensive silvery timepiece attached to a flat strand of worn and tarnished links is particularly attractive because its imperious owner has recently scolded me for daring to play with it. I pick up the entire clump of watch and chain. In the next remembered picture, I have made my way to the electric outlet on the nearest wall, and I am staring at it, as though trying to make a decision. Stabilizing myself on chubby knees, I stuff several links of the chain into one of the outlet's parallel slits.

With a sudden roaring wallop, a colossal burst of sparks and energy blasts up out of the wall as a paralyzing vibratory surge of electricity courses through every part of me and lifts my helpless body momentarily off the floor. Hearing my shrieking wail, terrified Momma flies out of some other room, screaming, no doubt certain that I have been killed. She gathers me up and I submerge myself into her softness. We are both weeping. She croons a gentle, familiar reassurance, but I am hysterical.

The pervasive feeling hovering over these horrifying images is not the sudden fright, but a sense of foreboding: something more is yet to come, and in its own way it will be as threatening as the terror I have just survived ...

The truth is not to be known. The only certainty is that the remembered sequence of images from that terrifying afternoon almost seventy years ago is inseparable from the dread of my father's coming rage; it is inseparable from the sense that Momma and I cowered in anticipation of its outburst just as we would cower in the torrential force of my father's wrath when it finally came.

Looking back on my earliest remembered years, I see my parents far less as a couple than as the sources of two quite disparate emotions Ñ emotions of golden safety with one and sporadic danger with the other. They originated from Momma, who lived only for me, and Daddy, who never quite understood how to be my father.

LOST IN AMERICA: A JOURNEY WITH MY FATHER, 2003

CHARLES CHAPLIN

One of my early recollections was that each night before Mother went to the theater, Sydney and I were lovingly tucked up in a comfortable bed and left in the care of the housemaid. In my world of three and a half years, all things were possible; if Sydney, who was four years older than I, could perf...

AGES 0-12

'My autobiography, however, is without any

artifice; nor is it intended to instruct anyone;

but, being merely a story, recounts my life,

not tumultuous events. Like the lives of Sulla,

of Caius Caesar, and even of Augustus, who,

there is no doubt, wrote accounts of their

careers and deeds, urged by the examples

of the ancients, so, in a manner by no means

new or originating with myself, do I set

forth my account.'

GIROLAMO CARDANO,

THE BOOK OF MY LIFE, 1576

ST AUGUSTINE

For at that time I knew how to suck, to be satisfied when comfortable, and to cry when in pain - nothing beyond.

Afterwards I began to laugh - at first in sleep, then in waking. For this I have heard mentioned of myself, and I believe it (though I cannot remember it), for we see the same in other infants. And now little by little I realised where I was, and wished to tell my wishes to those who might satisfy them, but I could not! For my wants were within me, while they were without, and could not by any faculty of theirs enter into my soul. So I cast about limbs and voice, making the few and feeble signs I could, like, though indeed not much like, unto what I wished; and when I was not satisfied - either not being understood or because it would have been injurious to me - I grew indignant that my elders were not subject unto me, and that those on whom I had no claim did not wait on me, and avenged myself on them by tears. That infants are such I have been able to learn by watching them; and they, though unknowing, have better shown me that I was such a one than my nurses who knew it.

And, behold, my infancy died long ago, and I live.

THE CONFESSIONS OF ST AUGUSTINE, 397-400

ARIEL DORFMAN

I was a baby; a pad upon which any stranger could scrawl a signature. A passive little bastard, shipwrecked, no ticket back, not even sure that a smile, a scream, my only weapons, could help me to the surface. And then Spanish slid to the rescue, in my mother's first cry, and soon in her murmurs and lullabies and in my father's deep voice of protection and in his jokes and in the hum of love that would soon envelop me from an extended family. Maybe that was my first exile: I had not asked to be born, had not chosen anything, not my face, not the face of my parents, not this extreme sensitivity that has always boiled out of me, not the early rash on my skin, not my remote asthma, not my nearby country, not my unpronounceable name. But Spanish was there at the beginning of my body or perhaps where my body ended and the world began, coaxing that body into life as only a lover can, convincing me slowly, sound by sound, that life was worth living, that together we could tame the fiends of the outer bounds and bend them to our will. That everything can be named and therefore, in theory, at least in desire, the world belongs to us. That if we cannot own the world, nobody can stop us from imagining everything in it, everything it can be, everything it ever was.

HEADING SOUTH, LOOKING NORTH: A BILINGUAL JOURNEY, 1998

HARRIET MARTINEAU

My first recollections are of some infantile impressions which were in abeyance for a long course of years, and then revived in an inexplicable way, as by a flash of lightning over a far horizon in the night. There is no doubt of the genuineness of the remembrance, as the facts could not have been told me by anyone else. I remember standing on the threshold of a cottage, holding fast by the doorpost, and putting my foot down, in repeated attempts to reach the ground. Having accomplished the step, I toddled (I remember the uncertain feeling) to a tree before the door, and tried to clasp and get around it; but the rough bark hurt my hands.

HARRIET MARTINEAU'S AUTOBIOGRAPHY, 1877

HANNAH LYNCH

The picture is clear before me of the day I first walked. My mother, a handsome, cold-eyed woman, who did not love me, had driven out from town to nurse's cottage. I shut my eyes, and I am back in the little parlour with its spindle chairs, an old-fashioned piano with green silk front, its pink-flowered wallpaper and the two wonderful black-and-white dogs on the mantelpiece ...

I do not remember my mother's coming or going. Memory begins to work from the moment nurse put me on a pair of unsteady legs. There were chairs placed for me to clutch, and I was coaxingly bidden to toddle along, 'over to mamma'. It was very exciting. First one chair had to be reached, then another fallen over, till a third tumbled me at my mother's feet. I burst into a passion of tears, not because of the fall, but from terror at finding myself so near my mother. Nurse gathered me into her arms and began to coo over me, and here the picture fades from my mind.

AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF A CHILD, 1899

THOMAS CARLYLE

My earliest [memory] of all is a mad passion of rage at my elder Brother John (on a visit to us likely from his grandfather's); in which my father too figures though dimly, as a kind of cheerful comforter and soother. I had broken my little brown stool, by madly throwing it at my brother; and felt for perhaps the first time, the united pangs of Loss and of Remorse. I was perhaps hardly more than two years old; but can get no one to fix the date for me, though all is still quite legible for myself, with many of its [features] ... Backwards beyond all, are dim ruddy images, of deeper and deeper brown shade into the dark beginnings of being.

REMINISCENES, 1881

HENRY JAMES

Partly doubtless as the effect of a life, now getting to be a tolerably long one, spent in the older world, I see the world of our childhood as very young indeed, young with its own juvenility as well as with ours; as if it wore the few and light garments and had gathered in but the scant properties and breakable toys of the tenderest age, or were at the most a very unformed young person, even a boisterous hobbledehoy. It exhaled at any rate a simple freshness, and I catch its pure breath, at our infantile Albany, as the very air of long summer afternoons - occasions tasting of ample leisure, still bookless, yet beginning to be bedless, or cribless; tasting of accessible garden peaches in a liberal backward territory that was still almost part of a country town, tasting of many-sized uncles, aunts, cousins, of strange legendary domestics, inveterately but archaically Irish, and whose familiar remarks and 'criticism of life' were handed down, as well as of dim family ramifications and local allusions Ñ mystifications always - that flowered into anecdote as into small hard plums, tasting above all of a big much-shaded savoury house in which a softly-sighing widowed grandmother, Catherine Barber by birth, whose attitude was a resigned consciousness of complications and accretions, dispensed an hospitality seemingly as joyless as it was certainly boundless.

A SMALL BOY AND OTHERS, 1913

SHERWIN B. NULAND

My father does not actually appear in my earliest memory of him. But the threat of his furious anger looms over the series of moments even as they are recalled.

It is in the form of single still images that I remember him from those early years. Each picture is preserved as though a camera had caught a series of lifetime's memories in individual blinks of an eye. Sometimes, an image is followed by a brief cinematic flow of film, but rarely more. And always a distinct emotion or mood is brought back to my mind when the pictures appear.

It is mid-afternoon and I have just spied Daddy's pocket watch and chain on a small table alongside the living-room couch. The sight of the inexpensive silvery timepiece attached to a flat strand of worn and tarnished links is particularly attractive because its imperious owner has recently scolded me for daring to play with it. I pick up the entire clump of watch and chain. In the next remembered picture, I have made my way to the electric outlet on the nearest wall, and I am staring at it, as though trying to make a decision. Stabilizing myself on chubby knees, I stuff several links of the chain into one of the outlet's parallel slits.

With a sudden roaring wallop, a colossal burst of sparks and energy blasts up out of the wall as a paralyzing vibratory surge of electricity courses through every part of me and lifts my helpless body momentarily off the floor. Hearing my shrieking wail, terrified Momma flies out of some other room, screaming, no doubt certain that I have been killed. She gathers me up and I submerge myself into her softness. We are both weeping. She croons a gentle, familiar reassurance, but I am hysterical.

The pervasive feeling hovering over these horrifying images is not the sudden fright, but a sense of foreboding: something more is yet to come, and in its own way it will be as threatening as the terror I have just survived ...

The truth is not to be known. The only certainty is that the remembered sequence of images from that terrifying afternoon almost seventy years ago is inseparable from the dread of my father's coming rage; it is inseparable from the sense that Momma and I cowered in anticipation of its outburst just as we would cower in the torrential force of my father's wrath when it finally came.

Looking back on my earliest remembered years, I see my parents far less as a couple than as the sources of two quite disparate emotions Ñ emotions of golden safety with one and sporadic danger with the other. They originated from Momma, who lived only for me, and Daddy, who never quite understood how to be my father.

LOST IN AMERICA: A JOURNEY WITH MY FATHER, 2003

CHARLES CHAPLIN

One of my early recollections was that each night before Mother went to the theater, Sydney and I were lovingly tucked up in a comfortable bed and left in the care of the housemaid. In my world of three and a half years, all things were possible; if Sydney, who was four years older than I, could perf...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherEbury Press

- Publication date2005

- ISBN 10 0091900336

- ISBN 13 9780091900335

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages640

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 103.66

Shipping:

US$ 5.39

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

THE BOOK OF LIFE

Published by

Ebury Press

(2005)

ISBN 10: 0091900336

ISBN 13: 9780091900335

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.7. Seller Inventory # Q-0091900336

Buy New

US$ 103.66

Convert currency